The Booms and Busts of Birth Rates

How Korea became the World Leader in Low Fertility

March 29, 2022

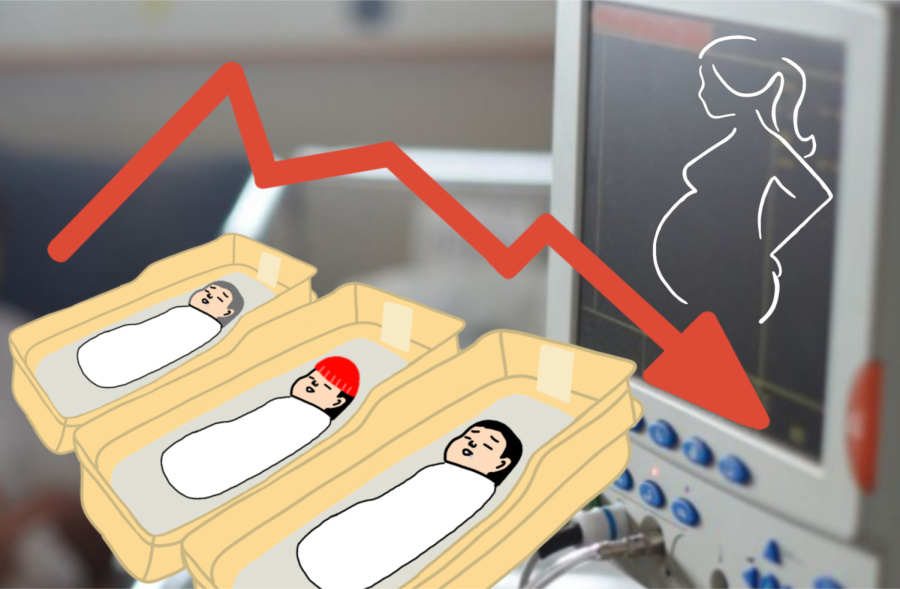

Fertility rate – the average number of babies women bear in their lifetime – is used to estimate how a population fluctuates over time. However, the outlook for South Korea isn’t so bright. Concerns are rising with a seemingly unstoppable decline in fertility rates. For a while now, the country has seen the lowest fertility rate in the world with recent data reporting only 0.9 children per woman (in comparison to a worldwide average of 2.5 children per woman).

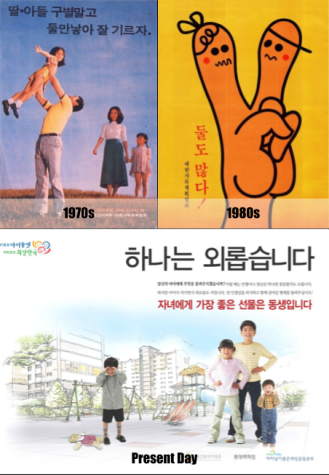

This ongoing crisis stands in stark contrast to the situation prior to the 2000s, when Korea was wrestling concerns with overpopulation. The propaganda used in these time periods show the evident disparity between then and now.

In the 1970s, the recommended number of kids per family was reduced from 3 to 2. Most couples during this time were absorbed with the popular idea of having as many sons as possible for their last name to be able to “live on” (due to the Korean custom of babies inheriting their last name from their father). Then, in the 1980s, the recommended number of children per family was once again brought down from 2 to 1.

The slogans used to promote these new expectations changed from “Have two kids and raise them well” in the 70s to “Even two is a lot!” in the 80s to “One is lonely” at present.

Many have attempted to uncover the cause for these problems, but have failed to pinpoint one definite source. Instead, politicians and experts are turning to many factors that might have contributed to accelerating this issue.

One of those factors is greater access to contraception. Not only have there been an increase in people’s accessibility, but also the increase in effectiveness of these methods due to developments in technology.

Analogous to the matter of births, Korea is also dealing with massive drops in marriage rates. In the past 20 years, the number of marriages in Seoul alone has decreased by 43%. Many experts and young people themselves agree that this is an indirect consequence of the economic hardships that Korean youth have to go through.

Preference for higher education is skyrocketing, and so is college tuition–which is not a light burden on younger students who have yet to even land a job. Competition for finding employment has also exponentially increased, which in turn leads to an even higher demand for education. Housing prices are at an all-time high as well, with the nation currently having one of the worst real estate markets of all time. With such difficulties stacking on top of each other, younger people cannot afford to form a family anymore, and naturally, marriage and fertility rates dipped.

Additionally, recent trends show more married women pursuing wealth and a higher standard of living rather than raising children. Korean society is no longer stuck in the 70s—women are rejecting the traditional expectations of them being full-time housewives. They’d rather fulfill their ambitions, make money, and become their own breadwinners.

Another issue is the widespread hyper competitive academic environment, as aforementioned. Since virtually every student in Korean schools need to go to hagwons (extracurricular academies) to be able to keep their grades high, the financial burden is heavy for parents–yet another one of the many reasons why married couples are reluctant to raise kids.

The decline in fertility rate gives birth to yet another problem – the fast-paced aging of the population. South Korea has been noted as one of the world’s fastest aging countries. Data estimates that Korea will become the world’s most aged society by 2067, with senior citizens to make up 46.5 percent of the population. If the population age continues to increase as the fertility rate keeps dipping, the effects will be devastating.

To help ease this issue, the government has been trying to implement policies that encourage pregnancy. One example is the 다자녀 혜택 (= multi-child benefit program). This program provides child care services, priority in housing purchasing services (주택청약), financial aid for college and medical care, etc.

However, skeptics question whether these policies lead to real changes. This thought can be supported by how the government reduced the requirement for a “multi-child family” from 3 kids to 2 this year (2022). This change in policy can be seen as a follow up action intended to boost the lacking improvement gained from the original program. On the other hand, this adjustment can also be reflecting the new view where people think even 2 kids is a lot.

The government should get inspiration from various successful strategies in other countries. For example, dating back to 1938, Finland gives out “baby boxes” that contain baby clothing, sleep items, hygiene products. and a parenting guide.

This policy greatly differs from what the Korean government is doing. Critics of the stratagem say that the monetary incentive that parents receive for pregnancy creates the immoral idea that an incentive for birth could be monetary gain – an unethical connection to make. This has led to some families having infants, but not actually raising the child with love and care.

The government should not just focus on economic motivations, but also on helping the parents feel rewarded for their hard work. Approaches like the baby box show the government’s effort to help parents feel supported both economically but also mentally.

Children are said to be the future of the world. With the number of babies decreasing, the bright light of Korea’s future will continue to dim out, unless we find a good solution that can bring back hope.