Social Loafers: The Missing Piece of a Complex Puzzle

My Group Project Struggles and Solutions

March 1, 2023

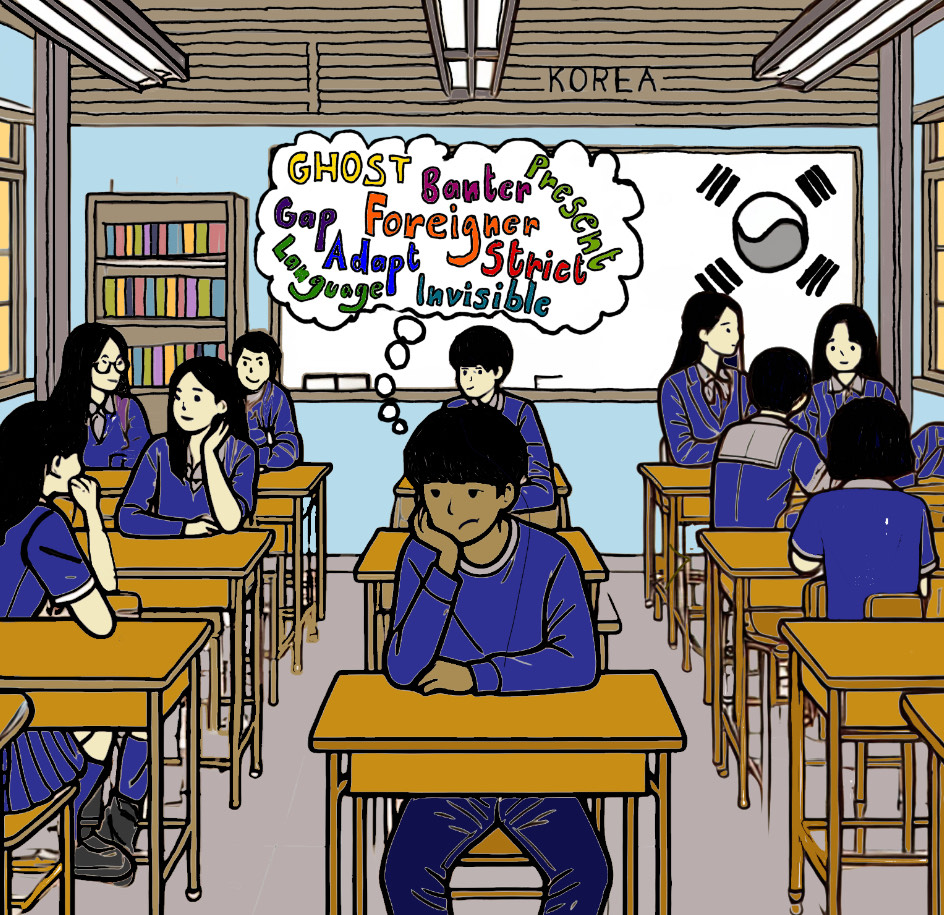

Late into the night, you smile at your laptop screen as you add the finishing touches to your assigned section of a group project. But you hit the right arrow button on the keyboard and you find your teammate’s slide blank.

I want to tell you about two recent group projects: For the first, I lucked out with membership in a harmonious team, but the other served as the classic case where I had to finish everything all by myself. One featured exceptional communication and teamwork, juxtaposed against another that suffered from minimal correspondence and effort. The latter experience led to a poor performance as we totally missed the mark.

The members of my second team, commonly known in psychology circles as social loafers, devote less passion to their tasks. Primarily, they don’t think their contribution matters to the group.

This inconsistency between group versus individual work made me question whether group projects benefit students. At times, I must admit, I fall for the lure of laziness. I assume other people will finish the work, just like how I did for others in the past.

Social loafing isn’t a simple problem. It stems from the fact that working alone motivates a person to perform well, for he or she feels pressure to earn the grade through their own merit. In a group, however, people tend to perform poorly because they think others will pick up the slack.

In fact, you experience this phenomenon all the time. Think back to your National History Day group. Did you lose focus and struggle with promptness? Did you think that other kids would work harder? But did the opposite hold true when you completed your solo STEM fair project? You met the deadlines and turned in a glorious experiment, didn’t you?

These universal moments are supported by scientific findings. In a German study, researchers asked people to scream as loud as they could. The research participants made twice as much noise alone as they did when joined by three others. The individual contribution continued to decrease as the size of the group increased. Numerous related studies reached similar conclusions: larger group sizes lead to less individual effort. These scientific conclusions translate into the real world, where team projects at school or work affect individual performance.

Let’s circle back to school projects in your DIS classrooms. Because you incorrectly presume someone else will undertake the responsibility, it leads to a decline in performance.

Don’t be too pessimistic, though: these tragedies can be avoided with team-building strategies. When aiming for your ideal goals, three fundamental factors arise as absolutely critical: specialization, communication, and organization.

First, specialization: divide the tasks along the lines of personal interests and hobbies. If you love reading, you can conduct the research. Your friend takes art classes, she can serve as head designer of the slide show. Your other buddy stays well organized for classes, then she can serve as team leader and dish duties out to the others.

Second, communication: be open-minded to new ideas and feedback. Be authentic. Accept criticism. Give constructive feedback. Stay on top of DIS email and chat messages.

Third, organization: set checkpoints to finish certain tasks by the agreed deadline. The team leader will hold you accountable. Use your daily planner, calendar, and tell the truth if you procrastinate.

As you burn the midnight oil on your next project, consider a better roadmap. What would you do this time around to deliver a different conclusion? Science tells us that group projects are destined for failure, but with my threefold approach, you, yes you, can break the mold.

Daniel Beck • Mar 2, 2023 at 6:43 pm

I wonder why social loafers do this in the first place… hmmm

Oliver • Mar 2, 2023 at 6:34 pm

I like how you ended article saying “you, yes you,”it feels like you are directly saying to me :). Well done!!