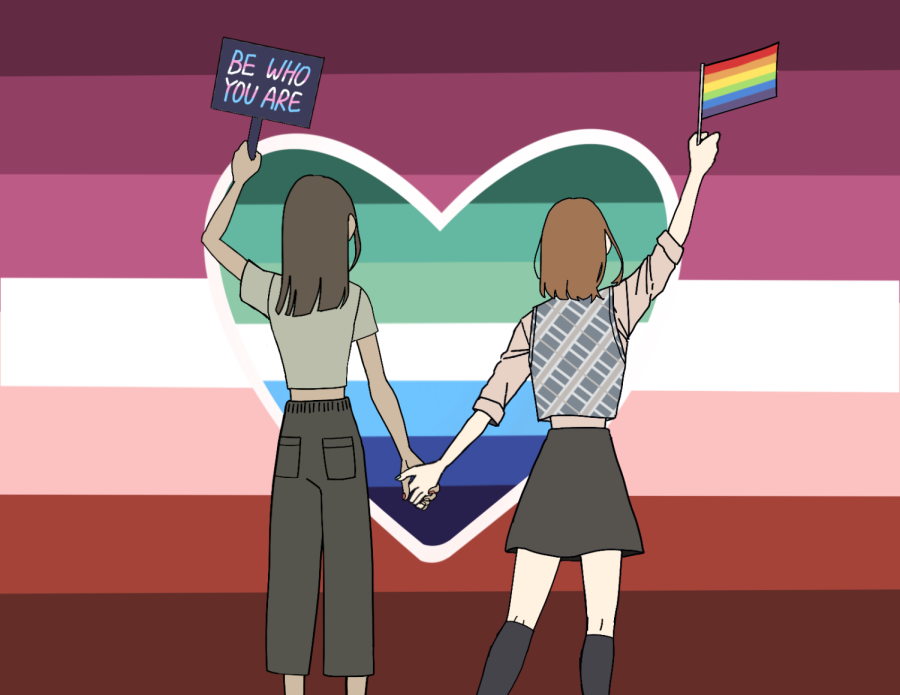

The Freedom to Love

Speaking Up About LGBTQ Issues In Korea

November 21, 2022

“That’s so gay” was a common insult in the ’80s and ’90s, but somehow, this low level jab survived to see the light of the 21st century despite a constantly growing voice for the rights of the LGBTQ community. It’s legal to fire employees for their sexual orientation in Korea. Gay marriage is still prohibited, and anti-LGBTQ communities are ever so active. How can this society change to be more welcoming and inclusive? I do not know. What I do know, though, is that the first step is to start speaking up about it.

Korea has been through constant, rapid change over the last century, but regarding the topic of sexuality, public opinion has remained stagnant. Countries that grew out of this prejudice, such as the US, Taiwan, and Australia, were not very much different 10 to 20 years ago from where we are now, but Korea still lags behind. People here don’t get criticized for being openly homophobic; most people, especially in older generations, don’t even know what it means to be homophobic.

The elderly aren’t the only ones who seem to think this way, though. Many young adults and students are still prejudiced against anyone outside the spectrum of cisgender-heterosexuality, and they aren’t hesitant in expressing themselves out loud. “You’re so gay, bro,” says a kid on the bus. His friend giggles, preparing for a similar retort.

I, trying to ignore their voices, look away and clench my fists, because what if someone who’s really gay heard it? What if they are not yet feeling secure about their own sexuality? What if they start doubting everything and everyone around them, unable to trust, unable to speak up? Maybe I am overthinking. Or maybe our community really needs to change.

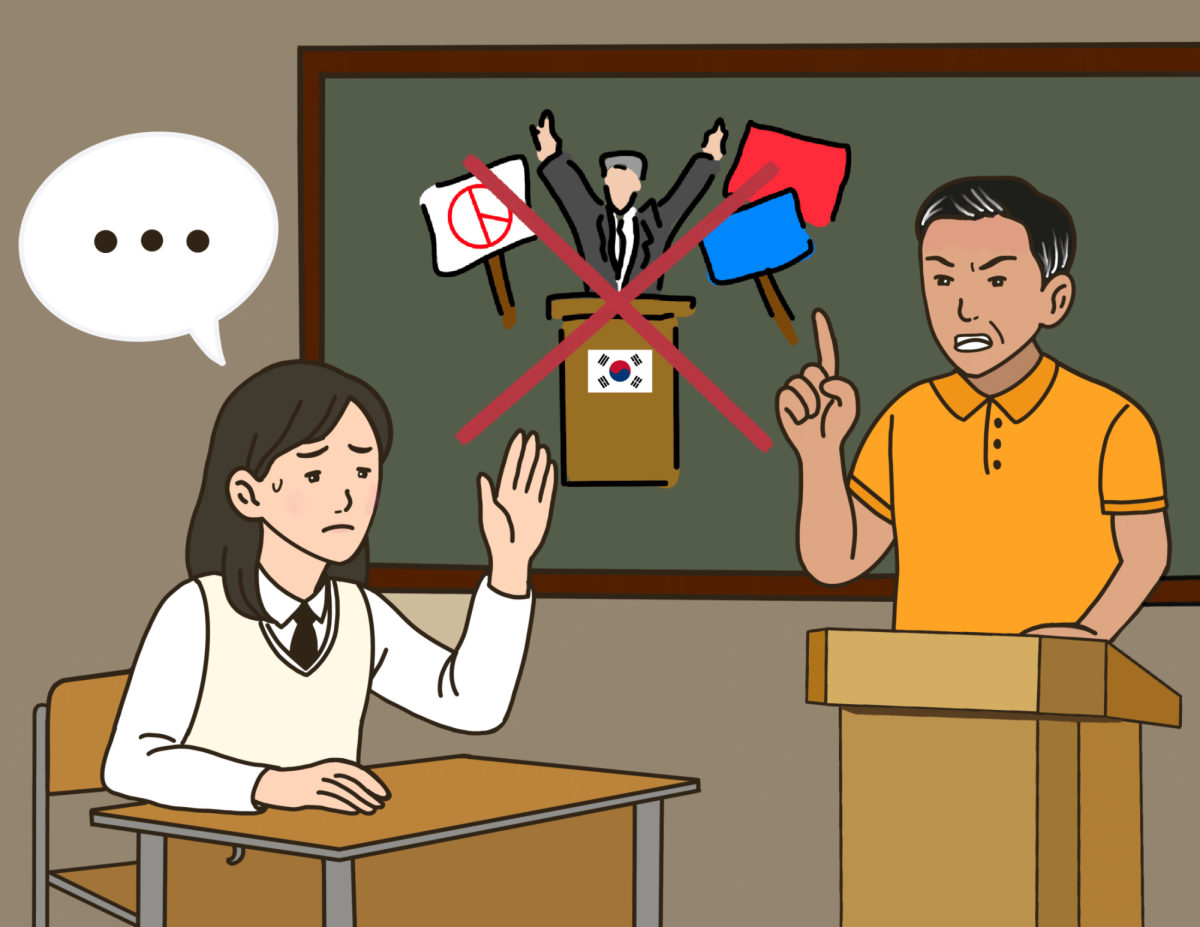

“I think that whenever it happens, it’s always about the need for more education and understanding, in a historical context as well, since sometimes people don’t know what these words have meant and how they were used to do things to people in the past. Their intent is just to be funny or clever, so they might not understand that those words can truly be hurtful to people. And you don’t have to be in the LGBTQ community to be offended by those comments. It’s a lack of understanding, which is why I think in school, it’s really important to help them understand the world in a larger context than they might’ve had before,” said curriculum coordinator Mr. Seward.

It took me by surprise, because before this conversation, it seemed to me as if the world was divided into two: the people who cared and the people who didn’t. Can a fight for controversial topics such as this one not always end up in a war of words? Are people only unaware, and would they actually care? Call me judgmental, but what I’ve seen in the short years of my life was mostly a repetition of asking for change, and being disappointed at the constant failure of my efforts.

It is difficult to eradicate what has been implanted in our brains for so long. Growing up in a Korean family, I never learned about the LGBTQ community until I reached middle school, and I remember that at some point in my childhood I thought that boys were only meant to date girls, and that girls were supposed to be petite, adorable creatures. It took time for me to accept that there were many genders, representations of gender, and sexualities in the world, and that it was okay to openly discuss them.

Since education regarding the LGBTQ community isn’t naturally provided for Koreans, as was the case for me, people are not likely to suddenly become enlightened of how unfair this society is for certain groups of people — it’s hard to speak out, especially so if it’s our closest friends that are the ones using homophobic slurs.

Even before we experience peer influence, the lens with which we view the world is already clouded by the ideals of our parents, who are likely to hold more traditional views on sexuality. Most Korean parents I know do not willingly expose their children to such topics, and when they do, it is usually with revulsion and warning: “Do not become one of them, and do not disappoint me.”

“We can’t dictate what people’s beliefs are at school, but we absolutely can teach people about being kind to each other, and we can teach about acceptance and creating a safe space where everyone feels welcomed,” is what LOVE Club advisor Mr. Cameron told me when I asked for a solution. I’d felt as if the influence we spread stayed within the walls of DIS, but perhaps, it could be that I was making a change.

It seems as though the adversity we feel against foreign ideas and people roots from never having opportunities for interaction with them. “I think it comes from a fear of not knowing. We make a lot of decisions out of fear, but it would be much easier if we could just make them out of love. And that fear keeps us from getting to love,” said Mr. Seward.

Distancing ourselves from those who we feel are different from us could be safeguarding the prejudice we have against them. At such times, reaching out for communication to those that are a part of a different community with positive intent would certainly help. “I think that it’s always going to be hard to affect change, and that it starts on a small level by person to person interactions,” Mr. Cameron explained.

It is truly mesmerizing how the power of a population can affect individuals; even people who aren’t necessarily insensitive when alone may act rude in order to conform to a biased group, especially on social media, where no particular consequences follow their actions. Mr. Cameron pointed out that when people are “online, there is anonymity, and I think people sometimes feel more emboldened to express their homophobia.” Truthfully, hate comments are the first things you see under videos on TikTok or Youtube related to a discussion on sexuality in Korea.

What’s ironic is that what helped me learn the most were also online communities – but those that accepted differences more openly and with ease. I felt scared to venture into a new world when everyone around me seemed fine the way they were, but once I was within the validation and support of both online and real-life friends, all of a sudden, everything cold and ruthless on the outside seemed so fragile.

“You should work on surrounding yourself with people who are supportive. If you’re friends with people who aren’t accepting you for who you are and they’re treating you poorly, of course tell them how you feel, but you don’t necessarily have to stick around,” Mr. Cameron said, and I completely agree. Though it is important to fight for equality and acceptance, it is also essential to surround yourself with those that understand you.

After some heated conversations and unpleasant moments, I now realize that there are many ways to cause change and provoke others to think. Our voices have power, but so do our actions. “It’s a long fight and a long journey, and people do so in many different ways. There are some young people who are progressive, angry, and more demanding for equality and justice and change, and there are slower, nonetheless determined groups of people who want to work within the system,” said Mr. Seward.

“Things seem like they’re changing very slowly until they do,” he added. And yes, things have changed over the years – just not enough for some people. And it will continue to do so, as long as there are individuals willing to speak up. The question of who we can love and who we identify as shouldn’t need permission. Fighting for those rights doesn’t need permission either.

Belle Kim • Dec 15, 2022 at 6:40 pm

I think being kind, understanding, and respecting others is important. And I think need to be brave to say this to change others’ thinking because it is the right thing.

Selina S • Dec 15, 2022 at 6:32 pm

My jaw DROPPED after reading that it is LEGAL in Korea for employers to fire someone because of their SEXUAL ORIENTATION. This is absolutely absurd. I empathize with the hopelessness. I sometimes doubt if someone can ever come out to their families safely. They will support the person but the viewing and treating of the person will change forever. Can all of these rallies change the perception LGBTQ+ is a mental illness? Hopefully I can see that happening. Awesome article though! I loved it. 🙂

Just a side note: why does someone have to “come out”? We should also try to fix our own perception of “norms.” Don’t expect someone to have a girlfriend or boyfriend because of their sex. We should also stop forcing someone who might be “gay” to come out or prove themselves. It’s uncomfortable and disrespectful.

(Sorry for the long comment lol hope you enjoy :))

Ms. Morissette • Dec 1, 2022 at 11:32 pm

This is such a beautiful, important article! Thank you for gathering and sharing these experiences and reflections for all of us. This will definitely be a mentor text for our journalism unit!!

Oliver Park • Nov 22, 2022 at 6:28 pm

I think the reason why Korean people are outdated from this thing is that most of the Korean shows about LGBTQ+ are kinda forcing us to be like them, which ends up as hatred towards this community.