Masking Away Our Insecurities

The Government Says It’s Okay Now, So Why Aren’t We Showing Our Faces?

October 24, 2022

It first hit me when I was in P.E. and Mr. Archer took us outside to play futsal. I realized that apart from Mr. Archer, I was the only student with my mask off. I could see that masks were clearly inconvenient, as students seemed hot and out of breath; despite this, all of my peers continued to keep their masks on throughout the whole period, regardless of the lifted COVID protocols.

It’s coming up on three years since the COVID-19 pandemic first started, and since then, wearing masks has become a daily part of our lives. As time passed, with the development of multiple vaccines, many countries have stopped enforcing masks, including South Korea lifting the outdoor mandate in May of this year. Yet still, in the streets, masks can be seen everywhere.

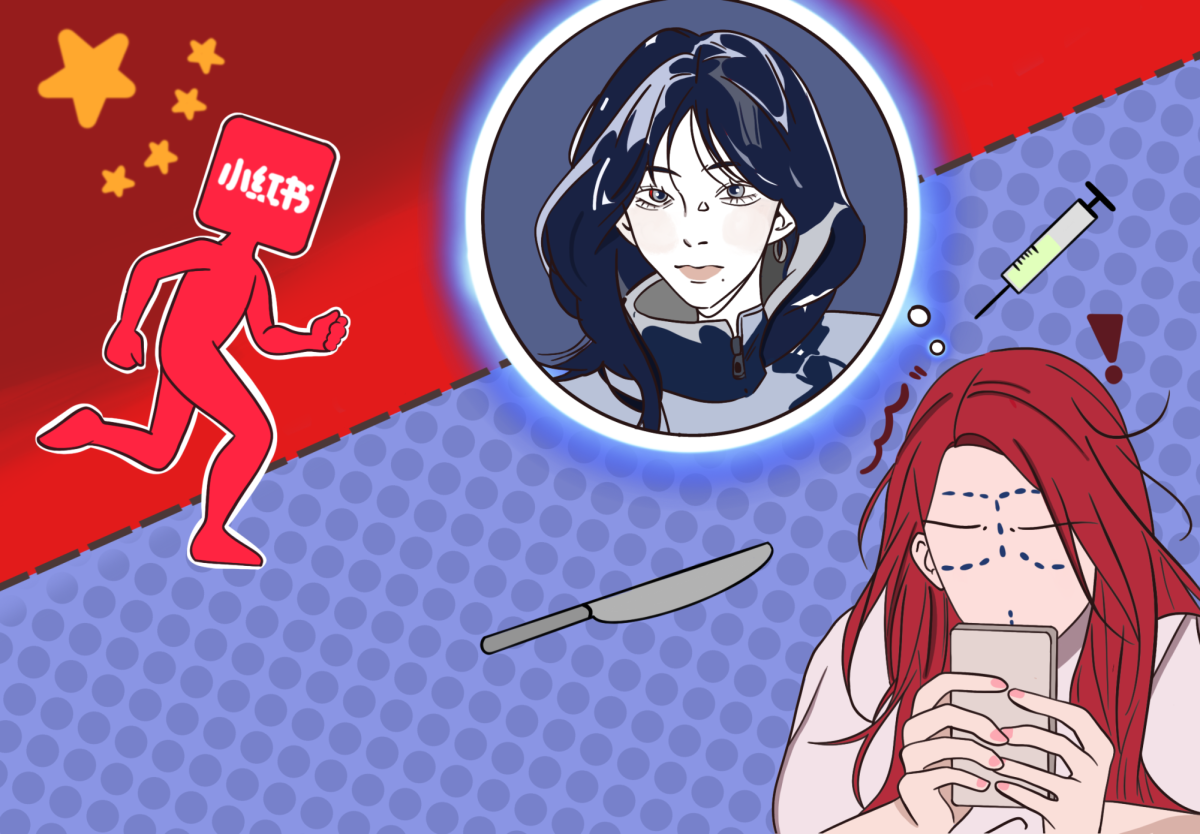

Korean society is generally known to prioritize physical attractiveness over all else – maybe academics is the only exception. This cultural standard is evident in its subways, bus stops, and social media, all plastered with advertisements for various cosmetic procedures and products. The desire to reach an unattainable standard of beauty continues to be the root of emerging body image issues.

The aforementioned mask mandate is an example of how toxic the beauty standard has progressively become, as many people admit that they are afraid to uncover their faces. Putting on a mask alters how others perceive you – you could either look conventionally attractive, or average, or worse, even ugly. Being in the unknown of what you look like to others is one of the main reasons behind our obsession with unrealistic beauty standards. Masks were once an uncomfortable and annoying piece of cloth we had to put on – now, it’s become a comfort zone for the insecure.

As teens, our insecurities are complex: we not only worry about trends, but we also go through body image judgment, peer pressure to conform, and identity formation, along with the susceptibility to social anxiety. Regardless of the pandemic, we’ve dealt with all of these before.

For the last three years, the government has strictly enforced mask requirements on its citizens. To unlearn the social concept drilled into most of us, it’s tough for people to go through this “transition period.” It also makes it much more difficult, as teenagers are hypersensitive to others’ opinions and the awkwardness puberty brings.

I think these different changes in appearance during adolescence already lead to a multitude of self-doubt, which the pandemic has indirectly worsened. Teens are hyper-fixated and alert regarding commentary on appearance due to the “spotlight effect”. I learned about the spotlight effect in AP Psychology, which refers to the aftermath of insecurities where an individual will feel as if all eyes are fixated on them. And with the increased time spent on social media and with peers, it’s no secret that body image issues worsen.

The choice of wearing a mask and the insecurities surrounding it have been magnified on social platforms through slang words such as 마기꾼 (Ma-gi-kkun), or “Mask fishing.” Essentially, 마기꾼 is the idea that someone appears more attractive while their mask is on, yet has many flaws underneath which makes them “unattractive.” This term went viral on TikTok, Instagram, and other social media platforms where the users, mostly teens, pointed out the “deceiving” mask fishers.

In all honesty, this degrading term only adds fuel to the fire that is the toxic media culture of shaming one for their looks. It was especially surprising when those around me would use this rude term to shame K-pop idols that didn’t live up to their expectations once the mask came off. While these celebrities are basically paid to sit still and look conventionally pretty, the severity of body image issues was magnified through the lens of the 마기꾼 term. What’s worse is that my own friends were throwing around this term lightheartedly towards celebrities – but what could these “friends” have commented on me regarding my appearance?

This year, students can finally sit closer together and face each other during lunch. After two years of looking at the back of people’s heads, it was extremely awkward to take off my mask and eat in front of my own friends. I felt self-conscious which started a spiral of overthinking. “Do I eat weirdly?” “Ugh, I have so many breakouts on my face.” “Eat with your mouth closed and chew quietly,” I would repeat in my head. It felt as if everybody was hyper-fixated on me, even if they weren’t. Due to the spotlight effect, I felt like I was being noticed more than I really was. Thinking back, I realize that nobody probably cared how I ate, but moments like these make me realize how much wearing a mask has indirectly and subconsciously messed with my self-esteem and image.

Although masks have become such a major part of our everyday lives, we shouldn’t allow them to affect how we hold and think of ourselves. It is a sad reality that we live in where teens are finding it uncomfortable and awkward to show their own faces to people they know, to the people they should feel comfortable around.

Jiyun • Oct 27, 2022 at 7:37 pm

Interesting!

Jodie • Oct 27, 2022 at 7:36 pm

Jodie good job

maisie • Oct 27, 2022 at 7:36 pm

good job jjojjo