Dismembered pigs garishly adorn the quiet streets of Buk-gu, where Daegu citizens assemble to halt the construction of a mosque. Residents hold pork barbecue parties and spray suspected animal fat to protest its establishment. What began as a small community effort to provide a place of worship for Muslim residents escalated into protests and legal battles. But beneath the headlines, there lies a more human story of Muslim students that struggle to navigate school life in a community that hesitates to welcome them.

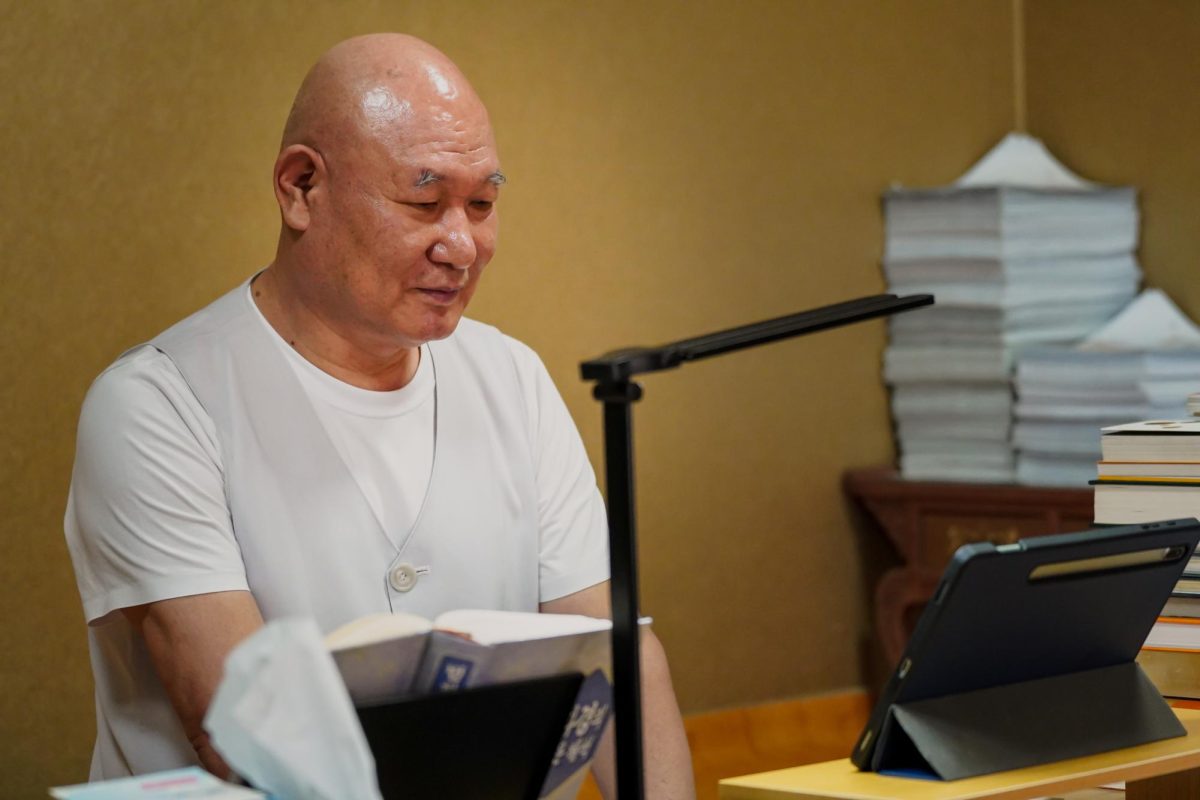

Dr. Ahmad Sheikh Faisal, the initiator of the Daegu mosque project, said, “Along with a prayer place, the mosque has a vital role in Islamic Culture. It serves as the community center where the residents living in its periphery gather for social events.”

Muslim students from Kyungpook National University initiated the project because “by the rules of the university, it can not provide a place for religious activities to any religious group,” Faisal said.

This problem stems from misunderstanding, not hatred. “There are many misconceptions and, in my opinion, ‘NAVER search engine’ is the main culprit of this,” he said. “Following are a few leading misconceptions that Koreans have about Islam: terrorism regarding jihad […], miserable lives of Muslim women…and hijab and abaya worn by Muslim females. They have completely misleading information regarding all these points.”

Soo Jeong Yi, a researcher with the Sogang Euro-Middle East and North Africa (MENA) institute, echoes the sentiment: “I believe the perception is fundamentally negative, but it stems mostly from ignorance about the other,” she said. “Due to a lack of objective information, people often harbor vague fears.”

This hatred transcends the streets of Dae-hyeon-dong. As Yi says, Korean culture often stigmatizes minority religions and immigrants. “The greatest factor is a lack of understanding of others, and a resistance to the idea of people who are perceived as ‘different’ entering one’s own sphere,” Yi said.

The resistance has tangible consequences for Muslim students in Korea. Damirkhan Makhamatzhanov, a Muslim student in seventh grade, said, “They didn’t ask me what I needed to do for food or things like that. I can’t eat pork, and they didn’t prepare separate food for me,” he said. “They understood when I told them and didn’t give me pork, but there was no alternative for it.”

While he felt accepted by friends, he felt unsupported by the school system. “If there are Muslim students, I hope schools can prepare separate food and also a separate room for praying,” Makhamatzhanov said.

But not all Muslim students experience the inclusion that Makhamatzhanov did. Eighth grader Yahyo Khorilov said, “I really had problems making friends. I couldn’t speak Korean, and they thought that I wasn’t cool enough. They were shy or maybe ignorant, but it was hard.”

Especially in earlier grades, classmates frequently left Khorilov out during lunchtime and teased him for his religious practices. “After I turned 12, it was required that I pray. So, I had to pray, but the school said that they can’t make space for me inside the school building and that I had to find a place outside of the school to pray. One time, I found a place and tried to pray outside, but my friends found me and teased me about it. They were like, ‘What are you doing? What is that?’ or ‘Is that your religion? That sucks,’” Khorilov said.

Eventually, things turned around for Khorilov. He said, “Eventually, when I was in fifth or sixth grade, they started to make different food for us. Because we couldn’t eat meat, they gave us eggs or cheese instead of meat, and that helped. But before fifth grade, it was really hard to eat.”

The school even designated a room for Ramadan. “I told them that we can’t go to school if we’re not going to fast, so they said that they are going to make us space for fasting. So we went to the room and we played with our friends or just read books,” said Khorilov.

These accommodations mirror what Yi describes as “gradual shifts” in awareness. However, she warns that we must remain cautious. “If support were given only to Muslim students, it could result in reverse discrimination. What is needed are more systematic and detailed policy approaches that respect and accommodate the diversity of students from various backgrounds,” Yi said.

The media plays a critical role in this issue. Faisal sees it as a tool that can spread fear, but also offer clarity. “Most of the people on social media share their thoughts and words which are based on the wrong and misleading information about Islam which is available online, but the Korean [news] does not [purposely] paint a negative picture about Muslims in Korea,” he said. “Even if a Muslim person is found guilty in a situation, they do not frame it as a religious issue,” he said.

“By providing objective information, [the media] can take the lead in improving awareness,” Yi said, “The most important strategy is, though it may sound cliché, education. It is necessary to properly educate people across different social classes and age groups to improve cultural awareness and perceptions of others.”

Muslims do not hope for special privilege, but recognition and respect. “The biggest problem is communication,” Khorilov said, “Schools could make us rooms, but not friends. You can’t make someone be friends with you. I think that’s the problem.”

As Korea continues to grapple with diversity, the Daegu mosque case reminds society that legal approval does not equal social acceptance. Yi said, “The conflict itself should be viewed as an example of how Korean society perceives other minority religions and immigrant groups as well.”

“Awareness of this issue is already growing, and preparations are gradually being made,” Yi said. “In the long run, I trust that it will work out well.”

Jio Kim • Sep 17, 2025 at 7:21 pm

I’ve read so much about this on the news, and it’s really sad how it’s still the reality for some people. Your article is a great way to give insight on what’s going on in the real world. Great work!!