In high schools across Korea, democracy is taught but not lived. Textbooks preach civic values like free speech, active participation, and the right to protest. Yet, from social media posts to student-led statements, speaking up often comes with consequences. Despite constitutional protection, students’ voices remain suppressed.

Democracy demands more than just elections; it requires understanding. Citizens must grasp how their government works, where it falls short, and how to challenge it effectively. Schools – meant to foster both intellectual and civic development – hold a key role in this process. They should guide students through structured political education while encouraging open dialogues.

Korea lowered the legal age for political party membership to 16 in 2022. The message was clear: teenagers deserve a place in politics. That said, many still face institutional barriers. 107 high schools across seven major regions still restrict political expression, according to the National Assembly’s Education Committee. To justify the limits, they cited vague phrases like “subversive behavior” or “student duties.”

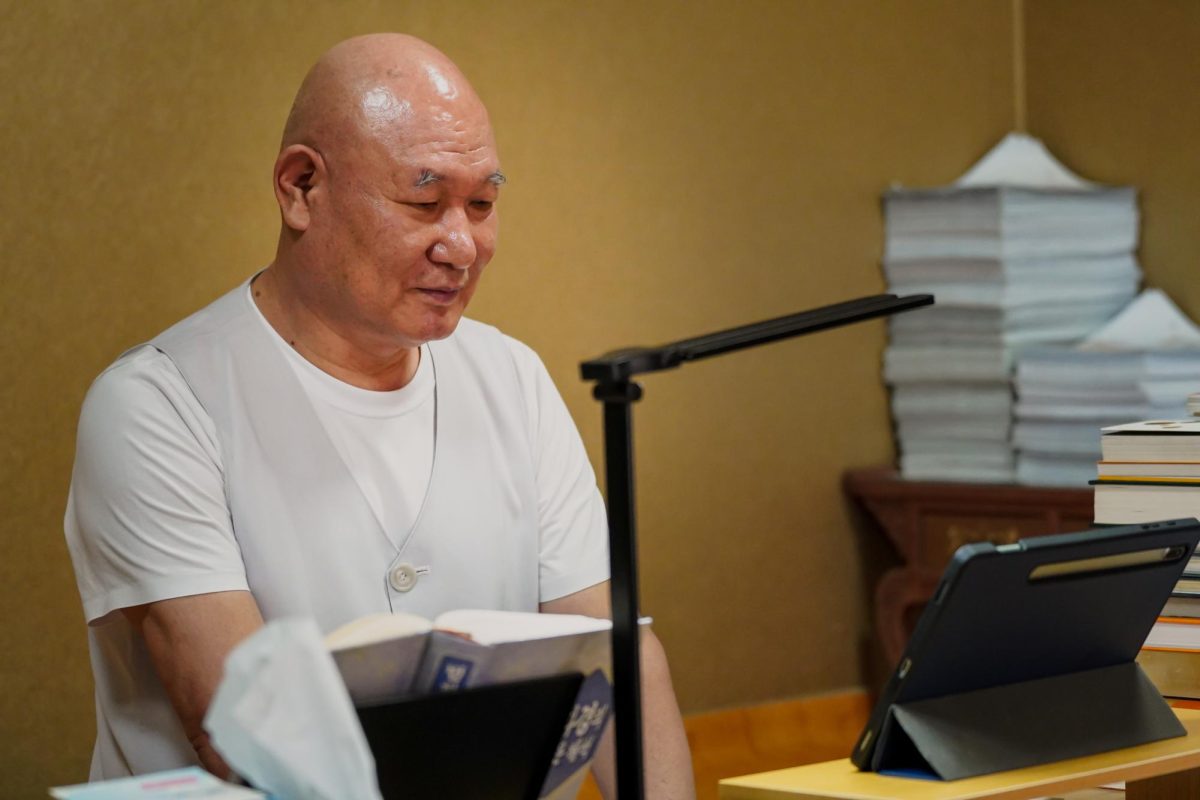

A striking case emerged at Seoul Yale Girls’ High School – it barred students from releasing a statement that condemned Yoon’s response to the alleged insurrection. This violates both law and logic, according to professor Jang-soo Chae from Kyungpook National University. “These restrictions reflect an unfounded distrust in students,” he said. “Denying them the right to participate politically contradicts the democratic ideals we teach.”

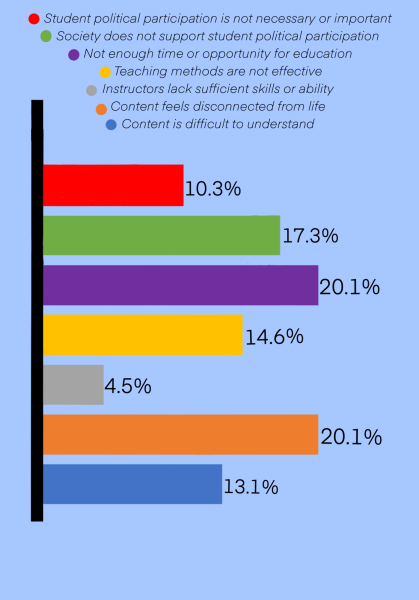

Surprisingly, this is just one of many examples. One in four Korean teenagers cited the lack of opportunities and information, both in and out of school, as a barrier to political engagement, according to the Korea Youth Policy Institute. Among them, 14.6% pointed to an “unsupportive social climate” as a key obstacle to participation.

(Jack Lee)

Even in schools without explicit bans, students quickly learn the conditionality of free expression. “Teachers here push their own biases, specifically about Yoon’s impeachment,” Hyeok Joo Choi, a student in Sindo High School, said. “Nobody says anything. We’re afraid to, because teachers write our university recommendations.” What’s acceptable to say often depends less on the content than on how well it aligns with the teacher’s opinions.

Schools justify such restrictions to protect children from political extremism and propaganda. However, when students can’t question or discuss freely, critical thinking suffers. As a result, they are left vulnerable to unchecked bias and misinformation.

“Students don’t just become politically literate when they turn 18,” professor Chae said. “Without the habit of engaging with politics to pursue their own and their community’s good, young people are more easily swayed by extremist ideas,” he said. If schools don’t take responsibility for building civic literacy, students will find less reliable sources like Instagram instead.

Notably, these constraints correlate with an elderly parliament. In fact, Korea has the lowest percentage of 30-to 40-year-old members of the National Assembly among all OECD countries: just 4.7%. Though various other factors contribute to this poorly representative government, underprepared youth only passively engage with politics.

Schools shouldn’t be neither battlegrounds for ideology, nor echo chambers of silence. They must offer a space where students can engage with real-world issues, question what they hear, and understand how politics intersect with their daily lives.

As political commentator Kyu-won Jeong said, “If we really want to nurture democratic citizens, education through active discussion is essential.” The goal isn’t to preach, but to equip. Schools must not only teach democracy but trust students enough to let them practice it.

Irene Lee • Aug 21, 2025 at 7:31 pm

this information was new to me.

Jio Kim • Aug 21, 2025 at 7:29 pm

I think this article gives a really good insight on the ideas of politics for a younger audience and the controversy surrounding this! Awesome work!!

Joseph • Aug 21, 2025 at 7:27 pm

I like the topic

Muhammad Khorilov • Aug 21, 2025 at 7:24 pm

I actually didn’t know that kind of thing was happening.

Jayden • Aug 21, 2025 at 7:24 pm

This is very true in DIS as well sadly