Disclaimer: This article contains the political opinions of the writer and does not represent the views of the Flyover.

In the aftermath of the Tohoku earthquake (2011), the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant exploded and decimated the once peaceful city. The explosion, along with the natural disaster, annihilated Fukushima. The incident emitted long-lasting radioactive debris, which drove away the residents for the next decade.

With time, the incident of 2011, like Chernobyl, slowly faded away from the public attention, until the Japanese government announced the release of its contaminated waters in 2023. In consideration of possible opposition, Japan addressed safety concerns prior to its initiation. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida said, “The discharge of…[contaminated] water into the sea is consistent with relevant international safety standards and will have a negligible radiological impact on people and the environment.”

However, considerable movements of criticism proved themselves inevitable. The Chinese government proposed a complete ban on Japanese seafood imports. Infuriated Chinese citizens made overseas phone calls to Japan, asking, “Why did you release the water?” I believe that such hostile actions expand a diplomatic issue into an illogical public conflict and exacerbate ethnicism.

In contrast to China, the Korean government showed mild reactions. In a ministerial conference, the Office of Government Policy Coordination announced, “We have judged that there have been no technical or scientific issues with the Fukushima discharge. However, we neither support nor agree with it.”

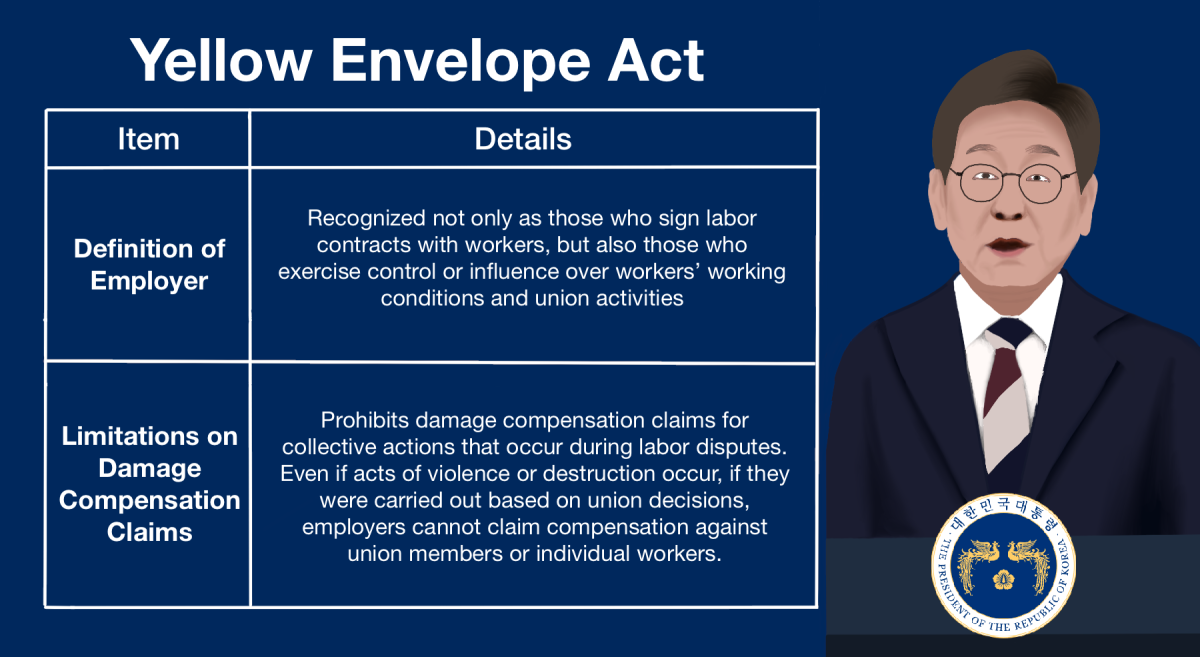

The liberal Democratic Party of Korea (더불어민주당) expressed disapproval of this conclusion. They hosted an international conference and described the discharge as “a violation of the London Conference (an international treaty signed in 1972 over marine pollution caused by waste dumping).” The conservative party accused this as an ‘action of political suicide.’

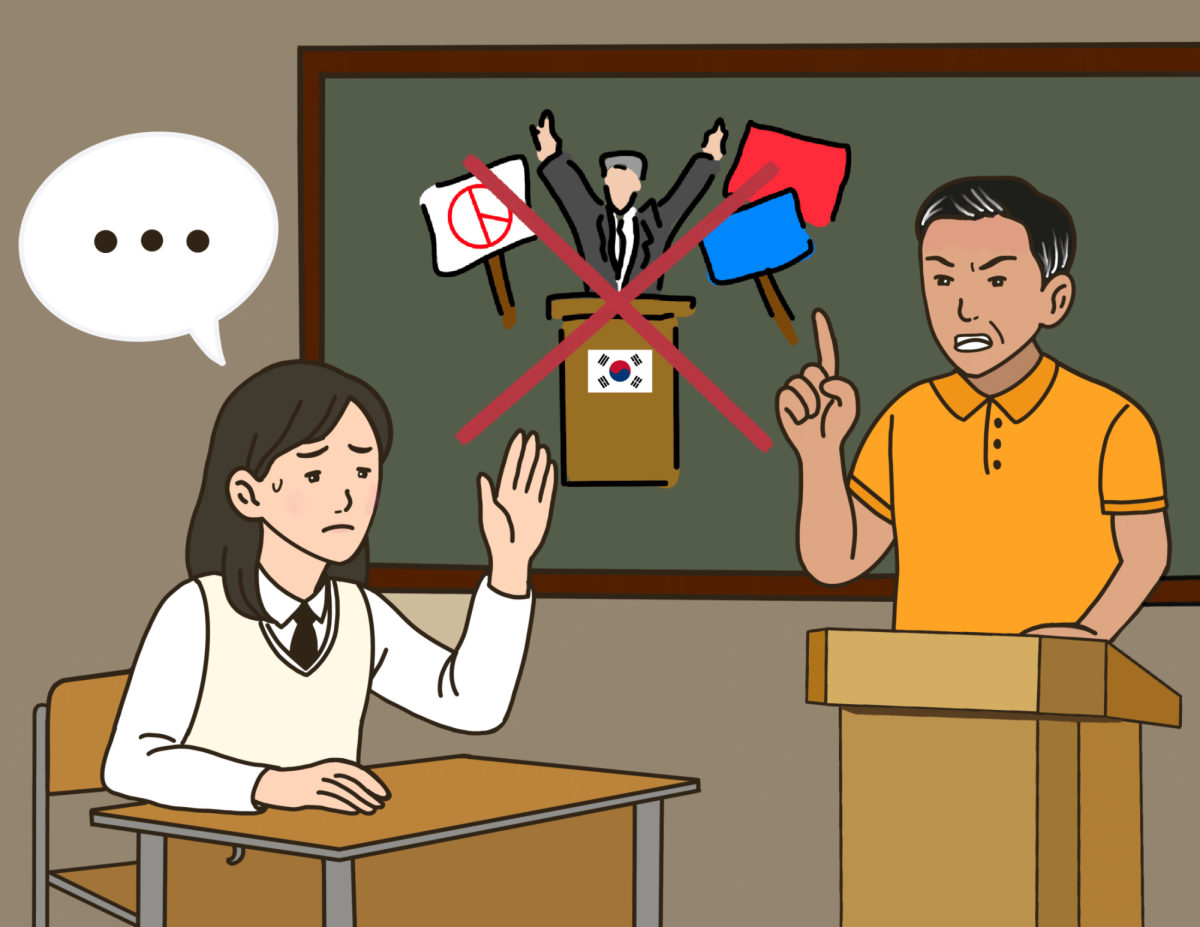

I believe that the stance of both parties reflect a short-sighted politicization. Throughout their armchair theories (claims made without actual investigation) Korean governors showed more care over their popularity than the gravity of the issue. The debate deteriorated into radical recriminations between conservative and liberal parties, which clearly does not benefit naive citizens.

Politicians who portray themselves as considerate leaders in public media never appear in support of the voiceless. Meanwhile, public fear of contaminated waters grew, and fishery communities of multiple Korean traditional markets showed concerns. A market owner in Busan said, “[Due to Fukushima] We barely sell a tenth [of the amount we used to sell]. We cannot stand this condition.”

While Korean politicians debated at their desks, Kishida took action. In order to minimize civilian damage, the prime minister visited multiple fishery markets that sold seafood from Fukushima, listened to the locals’ opinions on the situation, and even ate the food to emphasize its safety. Additionally, he combatted backlash with initiatives such as the government-led fishery support programs. “We will give our best effort to stop the economic embargo based on unscientific measures,” he said.

Governments must focus on the protection of their citizens as first priority. Japan instantly moved for its people’s aid. On the other hand, I see that Korean politicians took the Fukushima discharge as an opportunity to chew the opposite party out. In the future, I hope that our own politicians, upon facing a national crisis, rather watch out for its people’s security.

Ryn Seoryn Kwon • Sep 14, 2023 at 7:33 pm

I think this is a really big controversy in Korea. I agree with all the writers. I enjoyed the article. Thank you so much for this creative article