Once filled with eager students, the DIS Korean Studies after-school program—a government-certified dual diploma curriculum on Korean language, culture, and history—now sees a decline in enrollment alongside the hope of a future in Korea itself. Enrollment dropped, which left desks empty and lessons forgotten.

“It was totally useless for me and a waste of time since I’m planning to go to a U.S. college,” said sophomore James Kim. His words capture the shared sentiment of Korea’s younger generation, who feel increasingly detached from their own nation.

Today’s youth call their nation “Hell Joseon” (헬조선), a phrase born from the belief that no matter how hard they try, life remains futile. Behind this despair lies Korea’s “no-future crisis”—a deepening resolve that the system is rigged against them.

Most significantly, economic hardship, the medical school fever, and cultural detachment cast a gloomy shadow over Korea. The collapse of Korean Studies highlights how societal pressures make even carefully designed educational programs struggle to inspire students for a future in their nation.

Above all, political mistrust drives Korea’s no-future crisis, which corrodes both economic stability and public trust. Multiple unsuccessful policies from the Korean government, such as Moon’s real-estate control measures, minimum wage increase, and the Yellow Envelope Act, led to unemployment, economic recession, and exorbitant home prices—all of which made youths question whether they can carve out a living in the peninsula.

“I disagree with some of the policies, such as the Yellow Envelope Act. This act is very disadvantageous to big companies and would lead them to leave this country. Without them, the employment rate is going to decrease, along with the country’s future,” said Kim.

As companies exit the country and unemployment skyrockets due to abortive policies, job opportunities vanish, and economic anxiety engulfs the market. Citizens increasingly doubt the prospects of a stable career—according to a recent poll, three out of four young Koreans express concern about the lack of quality employment opportunities. Another survey found that one in five perceive success as elusive, regardless of the effort they put in—a 2.5-fold increase since 1990.

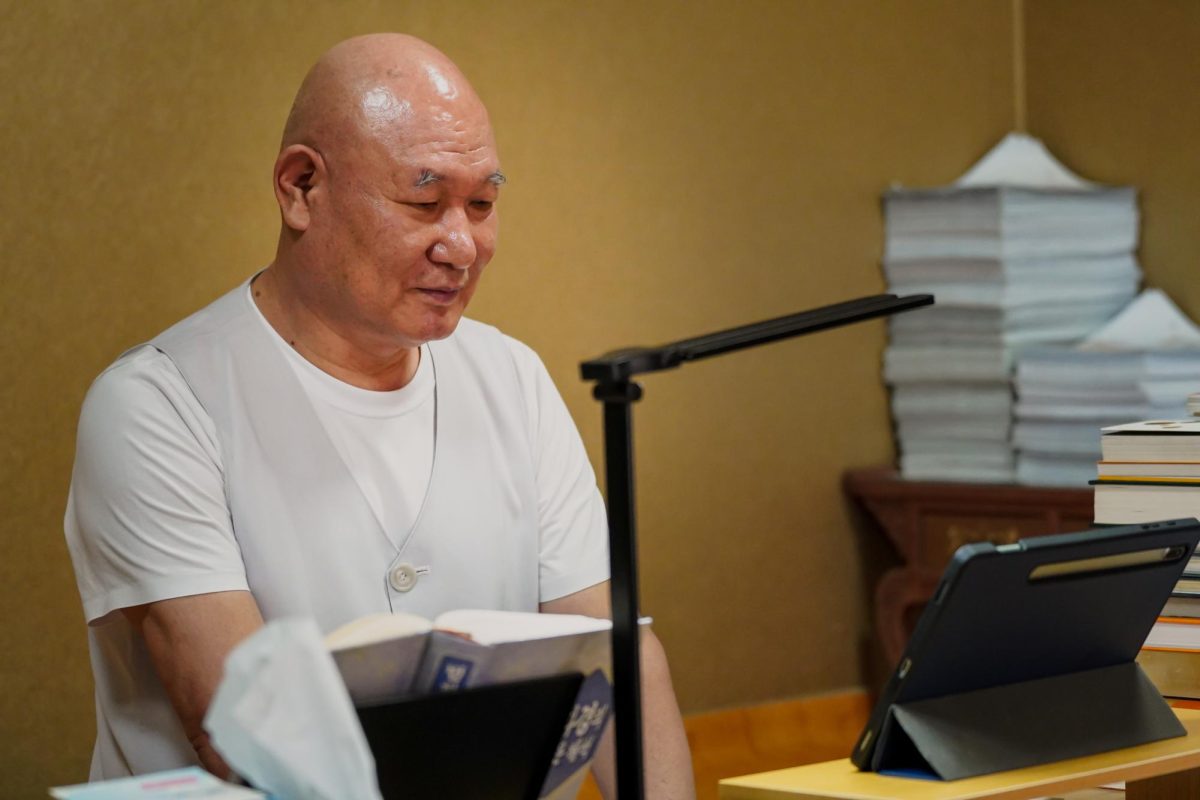

“This generation might be the first to be worse off economically than their parents,” said Professor Mooseop Kim, a statistics professor at Keimyung University. The idea captures the deep pessimism shared by many Koreans, who see that effort no longer guarantees progress.

This economic uncertainty intensifies the cultural pressure on career paths. Society equates success with medical professions alone, leaving little room for alternative paths to stability or prestige. “All the smart kids are planning to be doctors when they grow up, which is anachronistic in modern society,” said Kim.

This singular obsession pushes talented STEM students and researchers away from the nation. “Students who do well academically are expected to go to medical school,” said Ja Hae Hwang, a 10th-grade Korean Studies teacher. “Since they can’t follow that path here, they’d rather attend university abroad and live a more comfortable life.”

Even successful professionals—who serve an integral role in Korea’s infrastructure—express dissatisfaction. Gook Jong-Lee, director of the Regional Trauma Center at Ajou University Hospital, publicly criticized Korea’s medical and military systems, advising students to consider careers abroad. Indeed, nothing captures the national disillusionment more than the departure of gifted students and respected professionals.

This disenfranchisement plagues not just academically gifted youth, but also the general public as well. Foreign education, global media, and Western popular culture left younger generations with little incentive to learn about their heritage, and often overshadowed local customs. While Koreans gain international recognition with the K-culture craze, even that fails to reverse the cultural detachment.

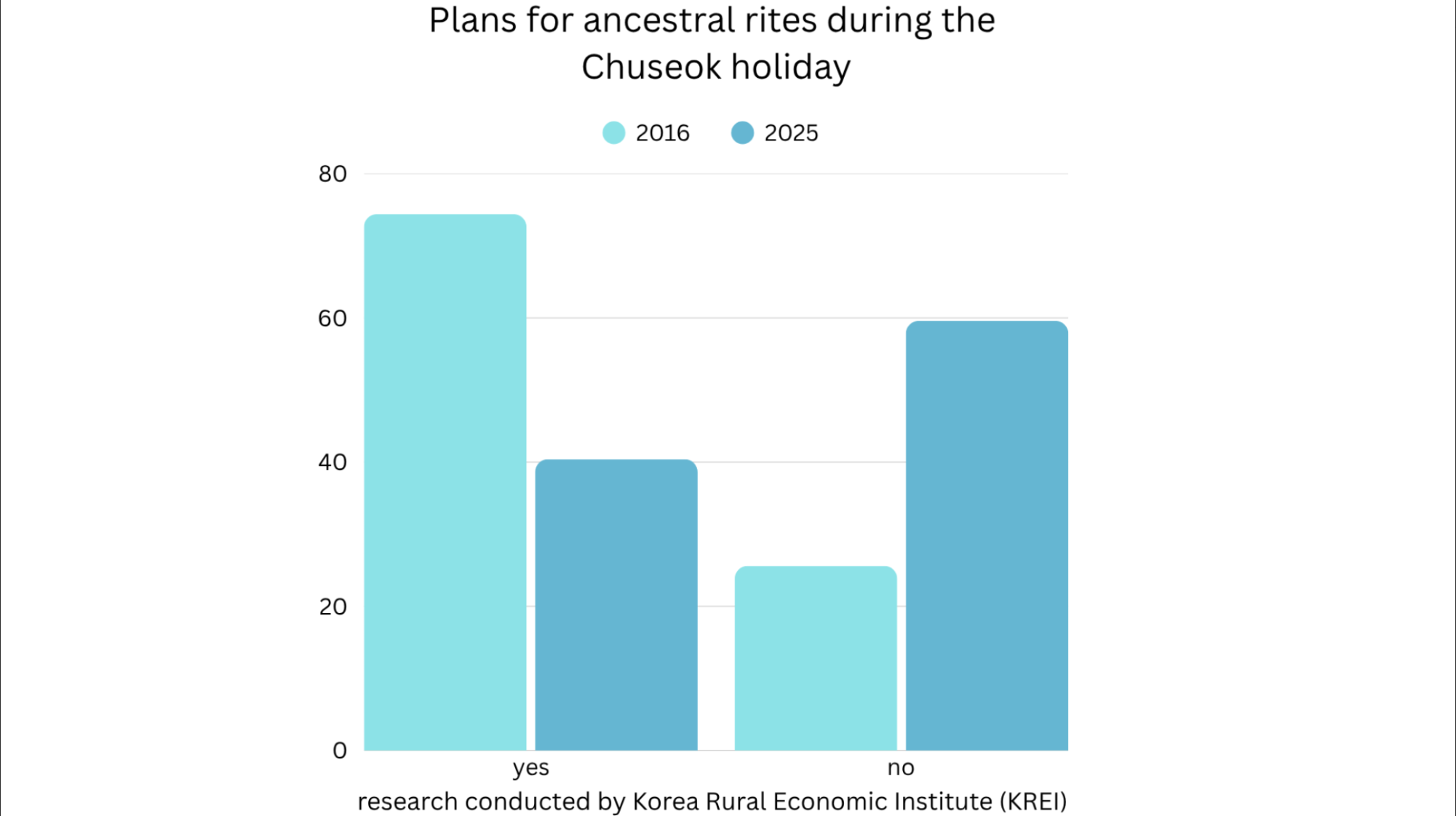

For example, on October 3, a report by the Korea Rural Economic Institute (KREI) revealed that only 40.4% of respondents prepared a charye table (차례상), the traditional ancestral rite held over major holidays like Chuseok. This marks a sharp decline from 74.4% in 2016—a sign of separation from cultural practices and, in turn, from the nation’s shared identity.

Hence, this heightened detachment deepens feelings of rootlessness. Without a strong sense of cultural belonging, many young people question why they should work to preserve or improve a society they no longer feel part of. For instance, according to Statistics Korea, only 69.9% of the “echo generation” (born in the 1980s-90s) report pride in their Korean identity, compared to 79% of baby boomers (born 1953-1963)- a noticeable generational gap.

Some described the “no-future” mindset as a generational divide. “This generation might be the first to be worse off economically than their parents. As Korea developed, survival became easier—but satisfaction became harder. Young people now value quality of life, yet face rising housing costs, job insecurity, and childcare burdens. Many think, ‘Rather than suffer, I’ll just live alone,’” said Professor Kim.

This captures how rapid growth bred comfort, but also disillusionment- leaving a generation uncertain of what their nation still offers them.

The consequences extend far beyond individual attitudes. Without cultural pride, the no-future sentiment deteriorates into not only an economic or professional issue, but an existential one. When the next generation withdraws from its roots, the nation risks forfeiting not only intellectual talent but also its integrity. Over time, this disengagement will erode civic participation and the cultural bonds that sustain society.

The revival of Korean identity hinges on restoring trust, opportunity, and pride. Policymakers must actively enfranchise youth and cultivate governance that commands confidence. In addition, strategic investment in innovation and employment must furnish ambitious individuals with compelling reasons to remain. Ultimately, educational and cultural programs should reaffirm heritage and reforge the bond between youth and their nation.