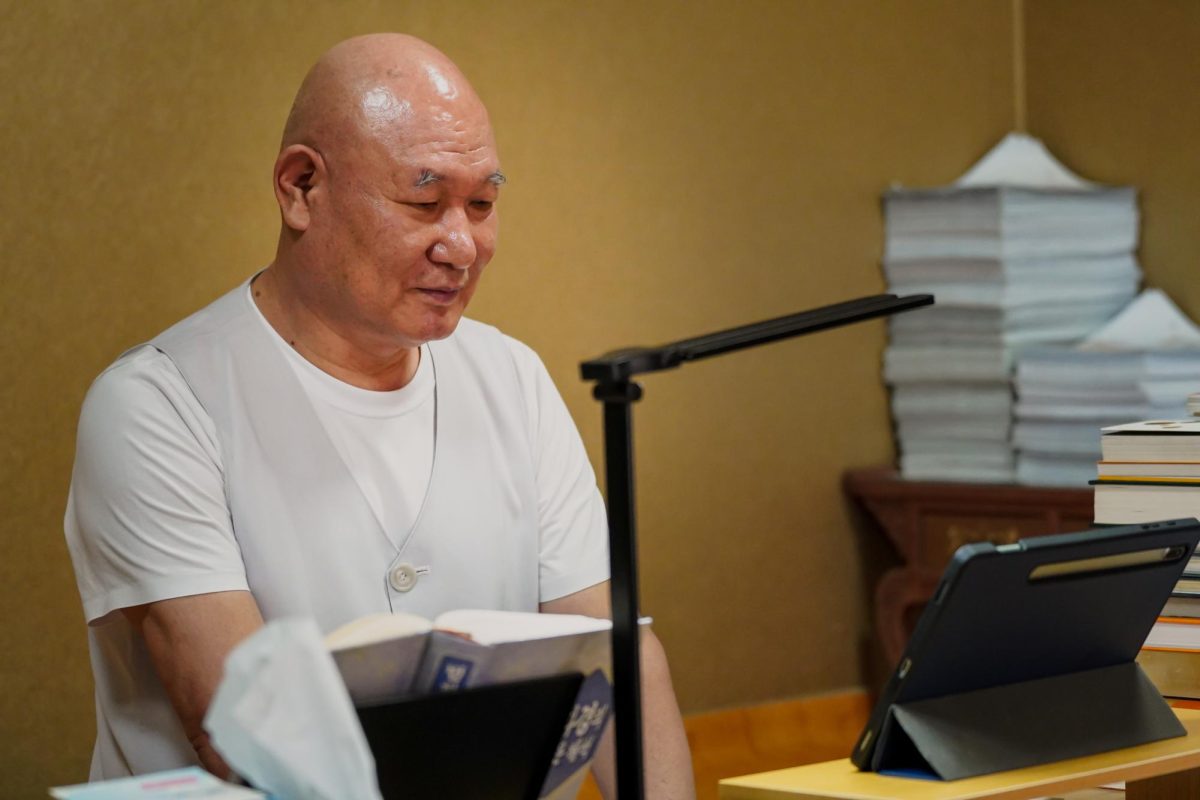

Secondary chemistry teacher Mrs. Gabriela Marchan didn’t begin her journey in a brightly lit classroom, but rather in the shadow of poverty as she negotiated for books with her father. “I come from an underprivileged background, so I feel like a lot of my memories that shaped who I wanted to become had to do with the lack of growing up,” she said.

In exchange for perfect grades, she received books in return. “Buying books was a luxury. I would have to bargain with my father [because] it was too expensive for us to afford,” Mrs. Marchan said.

While those treasured pages once felt like a burden, over time they became a source of infinite value. “The worlds in the books told me that what I saw around me, the poverty, wasn’t what life had to be,” Marchan said. “It made me excited to not stay there and see more and do more.”

Her potent excitement in learning alchemized into a passion for chemistry. Despite moments of self-doubt, Mrs. Marchan forced herself into the mold of a scientist. “I was supposed to be a chemical engineer. That’s when I started studying at university. I had done two years at university doing chemical engineering, I was super depressed because [chemistry] just wasn’t sticking the way that it was,” said Mrs. Marchan.

She continued, “Growing up, I tried to fit into this idea of being a scientist,” she said. “Scientists are very serious and smart, very genius, and I’ve never been like that. I’ve never been like, I got a math problem. I know how to do this.”

After confronting the harsh reality of science, Mrs. Marchan’s path veered away from equations and labs. What she mistook for a hindrance would later transmute into her greatest treasure—discovered through an American Sign Language course. “In this class, one of the assignments was to teach somebody else about American Sign Language,” she said. “I didn’t even know American Sign Language that well, but the teaching part of it made me feel like I could learn that language. I could excel in it.”

After a six-month pause, she embraced the shift and enrolled in an introductory teaching course. “I fell in love with creating lessons and trying to find a more engaging way of teaching the same old thing. So I just kept going at it. And after a year, I was like, ‘This is what I’m going to do. I’m going to teach,’” she said.

Yet her decision to pursue teaching meant confronting her father: the man whom she had bargained with and championed education as the route to financial security. “The hard part about it was not the decision to teach. It was telling my family about it because in America, teaching is not considered a good career. You don’t get paid well, it’s dangerous, and so my father was really upset,” she said.

“[He said], ‘I’m not going to pay money for you to go to college, for you to choose a job that’s going to make you poor again. I will not pay for your university anymore if this is the decision you’re going to make,’” she said. “It was either I get to focus on just studying and become an engineer, or I get to choose the path that I want.”

Ultimately, her decision to teach brought her halfway across the globe to DIS. “There are two feelings, and they’re totally opposing. The first one is that I feel a lot of pride that I was able to not waste my parents’ efforts because they worked hard and they struggled. Like tending the fields of an onion farm in order to be able to put food on our table, so we could be successful. So a part of me is really proud of that,” she said.

“[On the other hand] … there’s a lot of wonderful teachers here who have such a different background than mine. Sometimes I sort of get imposter syndrome. Can I be here? Is it right to be here? Am I doing something wrong and hurting others? Because I don’t really know that I am doing things the way that I should. Sometimes it makes me feel really small.”

Despite the internal conflict, Mrs. Marchan added that the classroom quickly became a place of renewal rather than doubt. “It gets me excited, and I try to make sure that excitement is felt by the students as well. We have such cool tools and opportunities here that I would have never dreamed of having myself. And so I hope that students can see how much of a difference it is making for their education,” she said.

The same curiosity that once bargained for books now fuels her to catalyze passion in students. “Books gave me an escape when I was younger and showed me that there was so much more to life than I was experiencing. Now that I’m in this position, I want to do the same thing but through science—inspiring kids through science,” she said.