**Disclaimer: The Jets Flyover editorial board must keep ‘K,’ a detainee formerly under ICE arrest, anonymous due to a government-issued compliance order for anonymity in all interviews with national media pertaining to the recent deportations from the US.

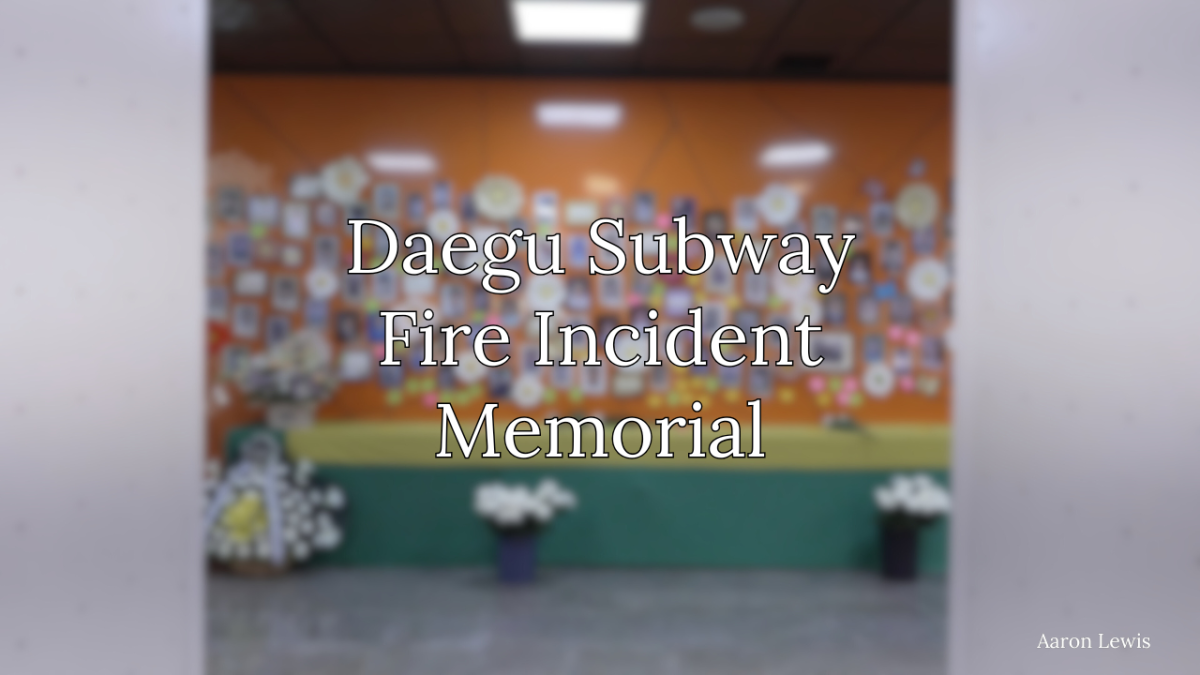

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), alongside Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), stormed a Hyundai Motor – LG Energy Solution joint battery factory in Georgia on Sept. 4. Over 300 foreign workers from Korea were arrested in what now stands as the largest single-site immigration raid of Koreans in U.S. history. Detainees returned after spending seven days in custody.

Workers struggled to process the scene. “It was like any other Thursday, as each of us was carrying out our assigned tasks. Suddenly, ICE and HSI burst in and started arresting us,” said ‘K.’ “Some of us were handcuffed and chained. It was a heartbreaking scene I’ll never forget.”

Detainees described unsanitary and abject conditions at the facility. “Mold, insects, and bugs were everywhere. We were treated the same as the criminals there, and that caused us great emotional pain,” said ‘K.’

Under the Trump administration, ICE raids have long targeted undocumented immigrants with greater scale and frequency: the detention rate reached a record-high of nearly 60,000 in August. Still, the event shocked many, especially given the conventional practice of worker dispatch and close diplomatic ties between Korea and the U.S.

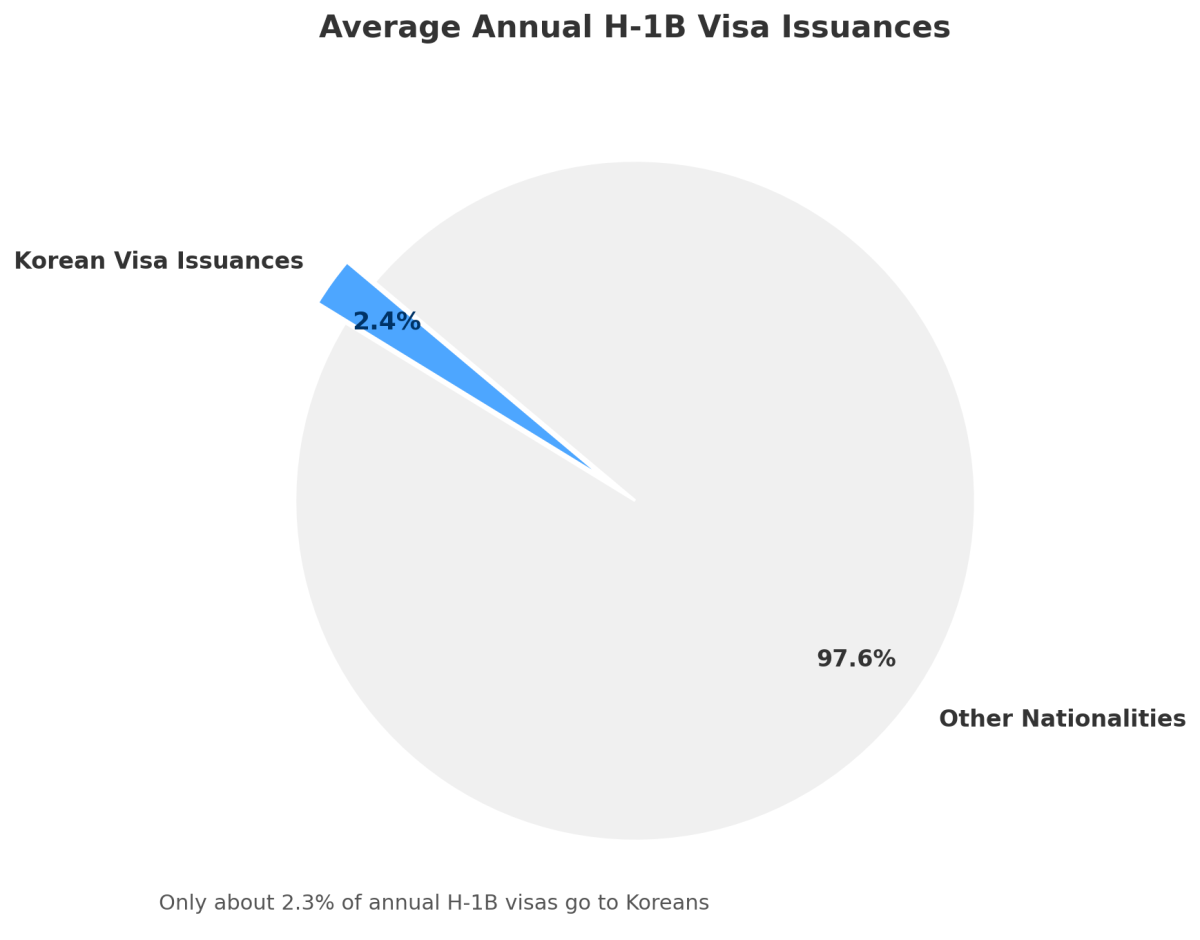

The arrested workers entered the U.S. on ESTA or B-1 visitor visas, neither of which legally permits hands-on construction work. For that, workers must hold an H-1B visa, the only category that allows employment in specialized fields. Yet, out of 85,000 available H-1B visas, Koreans only secured 2,000.

This low acceptance rate left Korean companies with no other choice but to send workers on short-term visas, which made it a common industry practice, although technically illegal. However, the recent flash raid exposed the risks to this approach. “This contradicts the long-standing custom and trust between the two countries,” said Seong-Min Ahn, the executive director of the Quality Division at Hyundai Motor Company.

The mass detainment disrupted factory timelines and operations. “Immediately after the incident, all the staff dispatched for equipment and technical support were forced to return, and activity continues to be hindered,” said Ahn. The impact extends beyond short-term delays: Hyundai and LG, which operate two and eight major production plants respectively, contribute significantly to the U.S. economy through investment and local hiring.

Central to the issue lies Trump’s contradiction, as Professor Minkyung Choi of the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences at Pukyong National University, said. While President Trump called for $350 billion in Korean investment, obtaining the necessary visas proved almost impossible. “The excessively complex visa procedure isn’t keeping up with the pace of global collaboration,” said Choi.

For multinational firms, the lack of visa clarity multiplies costs. With fines, delays, and lost technical labor, overseas operations and investment become unattractive. “If this kind of uncertainty persists, investment volumes may shrink, and new decisions could face delays,” said Choi.

The crackdown highlights the dangers tied to convenient yet unstable visa practices. It exposes inconsistency between global industrial cooperation and the rigidity of immigration policies. Now, the Korean government debates how to protect its citizens alongside strategic investments. As trade and tariff negotiations continue, whether the nation can walk the fine line between protection and partnership remains in the air.