**Disclaimer: This article contains mentions and hyperlinks to graphic content, including depictions of sensitive topics such as racism. Proceed with caution.

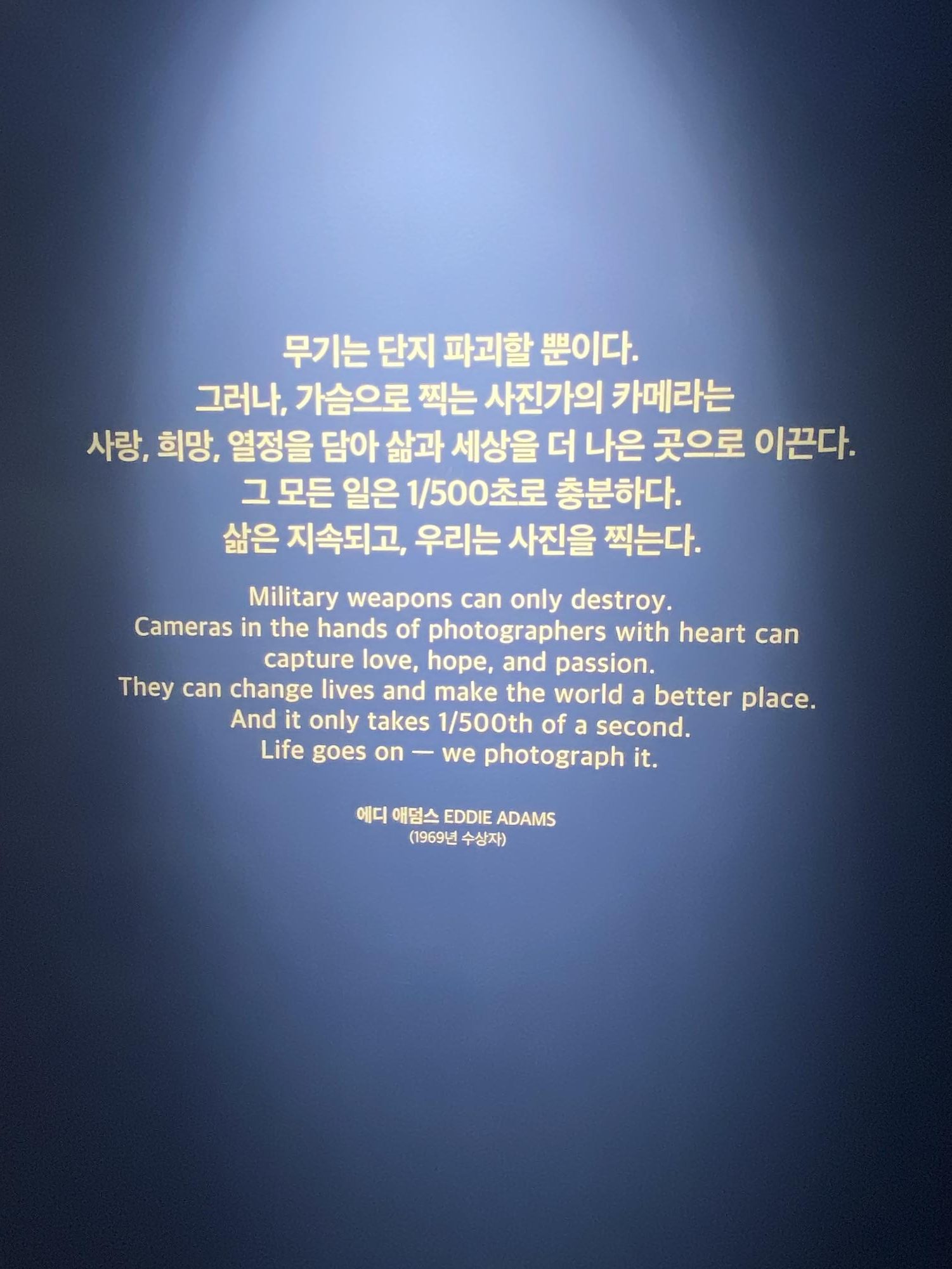

Each day, journalists capture instant but memorable pieces of time, from the mid-1940s to even this morning. Photography, one of the earliest ways to leave a legacy through high-quality images, conveys raw emotions.

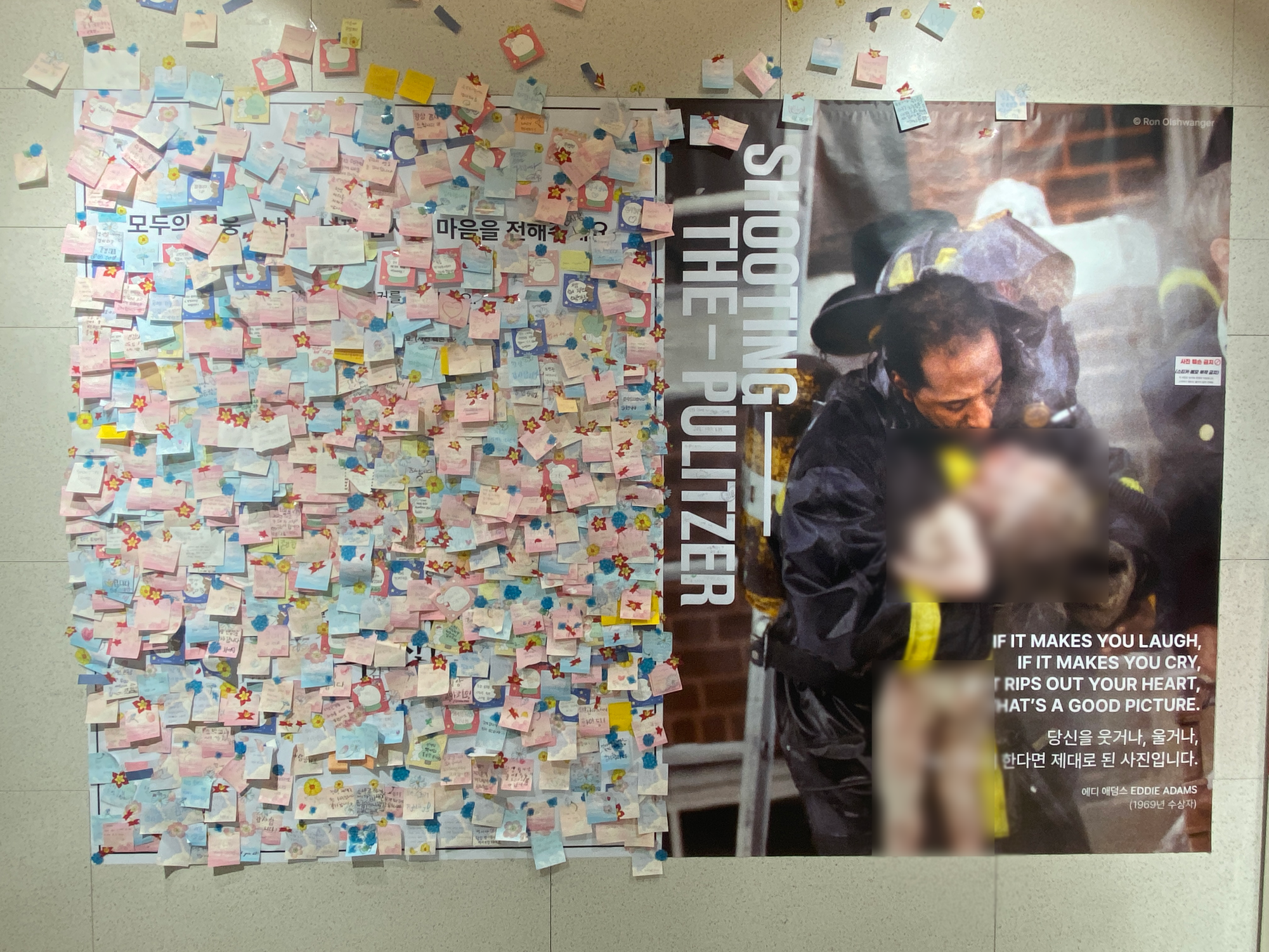

Fourteen outstanding journalists around the globe receive the Pulitzer Prize for their work every year. The historical pieces arrived in Museeum, located in Spark Land, Dongseongro, for the exhibition “Shooting the Pulitzer” from April 25 to Oct. 12. As a photography enthusiast, I bought the early bird ticket with a 50% discount in June to attend the gallery.

(Sophia Bae)

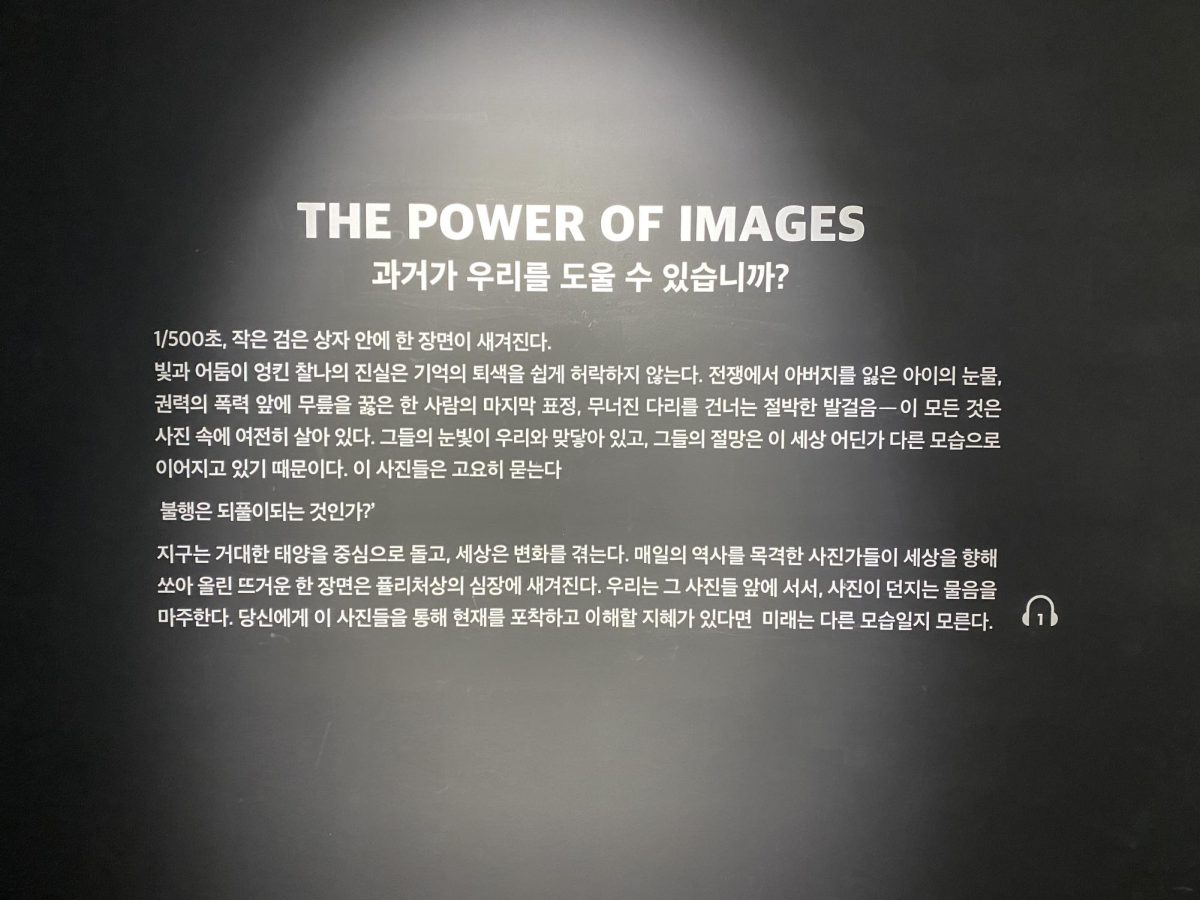

When I entered the exhibition through a curtain, a brief explanation of the time period greeted me. At first, it surprised me that the place not only displayed the images but also provided an overview for those without much background knowledge as well. But as I strolled through the whole expo, I came this prelude, which connected every piece into a theme.

The first several pieces had a clear theme: World War II. I anticipated photos that portrayed the harshness of the battles, but they defied my expectations and depicted the battles in a glorious manner.

For instance, pieces such as “Homecoming” from 1943 and “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima” from 1945 both focused on the heroism of the soldiers. Even though I resented such representation as it implicitly justified the war, I accepted it as a journalistic trend of the era—to convey news that would unite people and avoid conflicts—especially since the Pulitzer Prize evinces its historical significance.

The tragic side of wars started to emerge in the ’60s section of the exhibition, where journalists covered the Vietnam War. For instance, “Fleeing to Safety” captured the moment of struggle in 1965 where two Vietnamese families cross a river to avoid aerial attacks.

The stark contrast between the poignant depiction of innocent citizens lives torn apart and the glorification of the war left a lasting impression on me. “Fleeing to Safety” represented an immense shift in the perception of wars among the general public, where condemnation started to predominate over celebration.

From the ’70s, political and racial conflicts took the spotlight. At this point, I started to notice a pattern throughout all time periods thus far: no matter how much hostility exists in the world, we can still find moments of affection and harmony.

The contrast between “Violence in Boston” from 1996 and “Busing in Louisville” from 1998 brought this idea to life—while the former depicted a racist attack with the star-spangled banner as the weapon, the latter captured the start of friendship between two young boys of different races.

The brief two-year gap between the photos opens room for nuanced interpretation—some may see the contrast as reflecting the decline of Black rights, while others may note the children’s calm composure against the adults’ race-obsessed expressions.

But the theme of racism continued—for example, “The Shooting of James Meredith,” a photo from 1966, portrayed an incident of gun violence against a lawfully enrolled Black university student. Because of this, I believe that the children from “Busing in Louisville” had genuine, pure hearts that adults struggled to maintain as racial conflicts escalated.

I spotted similar contrasts in the ’80s section. On one side, the photographs depicted children with huge grins on their faces, while on the other, a child seemed nearly dead from starvation.

In addition to the heartbreaking contrariety, a photo of a teenager in a Romanian orphanage from the ’90s immediately caught my attention.

According to the explanation, the piece depicted an abandoned child—a victim of a radical population increase plan mandated by the government. The caregivers at the center lacked experience or motivation to take proper care of the children. Among them, however, there was one who looked after the children like her own, whose hadn the photographer capture.

This scene made me realize the importance of altruism in a world of unending conflicts: regardless of how bitter the world seems, one can still spread kindness to their surroundings and maintain compassion like the benevolent caregiver.

A photo of three Nigerian relay race participants, at the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games, elated from a bronze medal that they earned demonstrated a similar idea. The moments of happiness in our lives serve as a motivation to live despite various turmoils.

A video room separated the post ‘00s section of the exhibition. The room hosted two photos from the COVID-19 pandemic, but awfully different in mood and situation—one depicted a dead body wrapped in plastic from 2022 that could not even undergo cremation due to a lack of wood, and the other an elderly couple kissing through the barrier in 2021.

While I found hopeful themes in the paradoxical photos from the previous sections, this pair of images reminded me of how unequal the world can be. Despite the small tint of love and unyielding hope in the latter, the image still embodied a dystopian mood.

As I mulled over the photos from the exhibit, I realized that the photos deserved to receive the Pulitzer Prize particularly because they both conveyed raw emotions from the pandemic, whether that be hope or the lack thereof.

The exhibition “Shooting the Pulitzer” exceeded my expectations of a mere photo gallery. It deserves a rating of 10/10, and I would recommend a visit for everyone, but especially to those with an interest in journalism and photography—surely, the photos will give you the chills,