Tottenham senior Son Heung-Min shocked the public with his voluntary transfer to Los Angeles Football Club (LA F.C.) in Major League Soccer (MLS), which he announced at his last pre-season match held in Seoul against Newcastle United F.C. Within hours, numerous articles and videos labeled Son as “a waste of twilight years” or “wrongly kicked out of the team,” Numerous Korean fans accused and belittled the national hero.

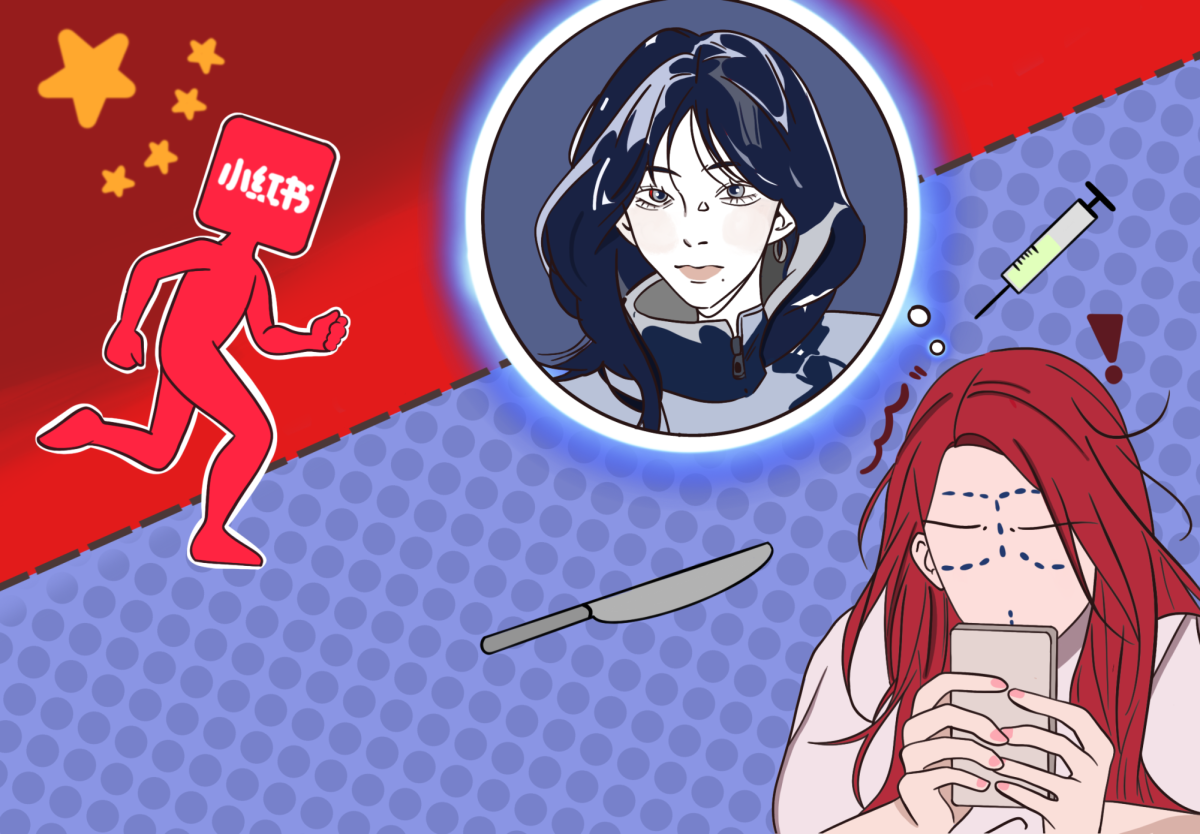

As Son’s case exemplifies, sensationalist journalism in the South Korean sports community remains a concern, largely due to the lack of regulation from press agencies. Routinely, outlets slap on flashy titles with terms like “exclusive” or “shocking” to significantly increase viewership. The embellished content easily sways the audience and their opinion.

Due to the extreme level of misinformation, the Korean community coined these reporters “giregi,” a compound word formed with “journalist (gi-ja)” and “trash (sseu-re-gi).” The definition originally denoted journalists who publish false news. But “giregi” has since evolved to describe a broader social phenomenon, where approximately 34,000 reporters across media outlets simply copy other press releases from news agencies.

Ryan Chae, a 12th-grade football enthusiast, described the severe sensationalist journalism about Son even before his departure. “When Son played for Tottenham, I saw dozens of articles with similar headlines and photos, all targeting him. The press definitely hated Song Heung-min throughout his career.”

On the other end of the spectrum, some media glorify Son. Mr. Gall, a passionate supporter of Tottenham, said, “The difference in Korea is that Son Heung-Min carries national symbolism, so the sensationalism cuts deeper. Since everything is now just about must-clicks and views, the media pumps up a slight tumble in a team’s early season to a dramatic swing.”

Thus, biased journalism polarizes fan bases for particular players and teams. Especially on social media and in community portals like “Football Gallery,” sports fans have turned online forums into a battleground.

The well-known “Son-ppong” (reckless support of Son) versus “Son-kka” (rash opposition of Son) culture, once prominent in South Korea, presents a clear example of biased media in society. Crooked fans took over the comments section, and Tottenham and its players were strongly criticized and blamed for Son’s poor performance.

While the public sees through the sensationalist façade of journalism, Korean news agencies refuse to budge on their current guidelines and policies. Especially in “Nate Sports” and “Sports Josun,” polarized content thrives. Park Ji-Hyun, secretary of the Freedom of Press subcommittee of the Journalists Association of Korea, said, “News agencies have a monetary penalty system and also encourage users to report offensive or manipulative content. These measures will help to balance press freedom with accountability.”

With continued interest in stimulative headlines, reporters argue that their writing style is a response to subscriber demand. Sports reporters often deflect public criticism and emphasize their competitive environment. They claim that sports articles differ from general news because of the frequency of hourly posts and broadcasts, which places sports journalists in a far more competitive environment than others. While the assertion explains the motive behind loud titles, it overlooks the ripple effects of such faulty broadcasts.

While sports journalism remains prominent in South Korea, unchecked sensationalism undermines sportsmanship, erodes public trust, and harms athletes and teams. Beyond light fines, sports organizations must implement stronger measures, and both reporters and the public must recognize that, without proper oversight, journalism will continue to deepen division instead of understanding.