Inside factory floors and corporate offices, tension simmers. Three months into President Lee’s inauguration, the conspicuous labor policy “Yellow Envelope Act” shakes up the workplace. Passed on Aug. 24, the act redefines power balance through amendments in the Trade Union and Labor Relations Adjustment Act. Now, two major changes await implementation: one expands collective bargaining rights, and the other broadens strike protections.

The first amendment extends the definition of “employer” and allows subcontracted workers to negotiate directly with companies that control their job conditions. This means that subcontracted laborers, often the most vulnerable in companies, now gain the chance to speak to the primary employer. “If workers can communicate directly with their principal employers, we’d be able to prevent exploitation,” said Professor Chur-Woong Park, the Director of Organization at the Korean Teachers and Education Workers Union.

Critics argue the measure overburdens companies with accountability for workers they don’t officially hire. However, this is not an issue. Because negotiations operate as a coordinated process through a single bargaining channel, streamlined inputs can prevent undue strain.

The true challenge lies in the ambiguity of the term “real control.” Since Korea’s subcontracting structure stretches across multiple layers – Samsung with over 700 first-tier suppliers and Hyundai about 350 – accountability becomes unclear. “If a company sets key job conditions like work hours, they must bear the responsibility,” said Professor Bo-min Kim of Kyungpook National University. “But we need clearer institutional standards set by the Central Labor Relations Commission to determine that,” said Kim.

The second amendment changes how businesses can respond to strikes. Previously, companies could request compensation for walkout damages, except in cases directly associated with labor conditions like wages. However, they’re now barred from seeking compensation, even for sabotage strikes in response to routine management decisions. These include rearrangement or relocation measures, which define a company’s core business strategy.

While companies can still file compensation claims, “the burden of proof may be excessively placed on the company, making it unlikely for the claim to succeed,” according to the Daeryun Law Firm. Ultimately, companies must absorb the losses.

This expansion ensures stronger voices for workers. “If the company refuses to negotiate a reasonable demand, we must protect our rights through a strike,” said Jeong-Yeol Kim, a worker at corporation Bokju. Yet, apprehensions about its potential misuse emerge. With no consequences, workers might request excessive negotiations or go on a walkout whenever demands go unmet.

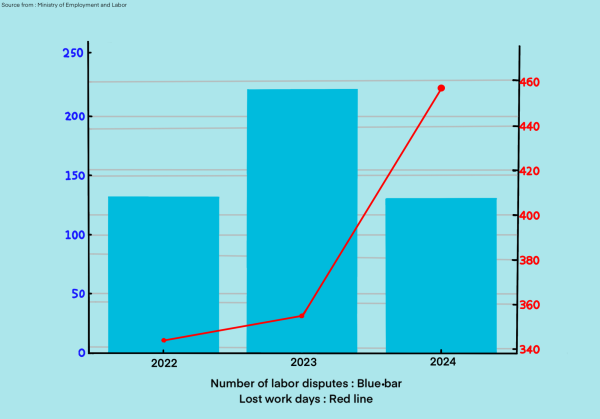

In fact, the number of days lost to strikes in 2024 increased by 29% compared to the previous year, according to the Ministry of Employment and Labor. Strangely enough, labor disputes have recently intensified following the law. For instance, the construction union protested in front of SK headquarters to demand increased hiring for union workers.

Companies fear these numbers could proliferate. “Naturally, we expect to see an expansion in the exercise of strikes. It seems there’s no way to prevent losses caused by illegal or manipulative strikes or demands in advance,” said Hyung-seok Kim, the employer at Bokju corporation.

This environment could harm both sectors. As firms struggle to make prompt decisions in response to fluctuating financial conditions, they may make choices that adversely affect the workers. “Corporate management and investment activities may shrink, and the resulting damage could be passed on to workers as a reduction in jobs,” said Kim.

Labor rights remain crucial for fair and humane job conditions, and expanded negotiation rights help support them. That said, assigning all strike-related losses to companies risks hindering economic development. Indeed, company growth creates jobs and improves workplace conditions, the very goals of labor unions.

Policymakers must balance regulatory oversight and business flexibility. Strategic decisions, provided that they comply with labor laws, deserve respect. In addition, constructive dialogues between labor and management must take place to prevent escalation in the first place. To complement this, the government should introduce clearer standards for worker protection and strengthen liability provisions for illegal or violent actions to promote healthier labor-management relations overall.