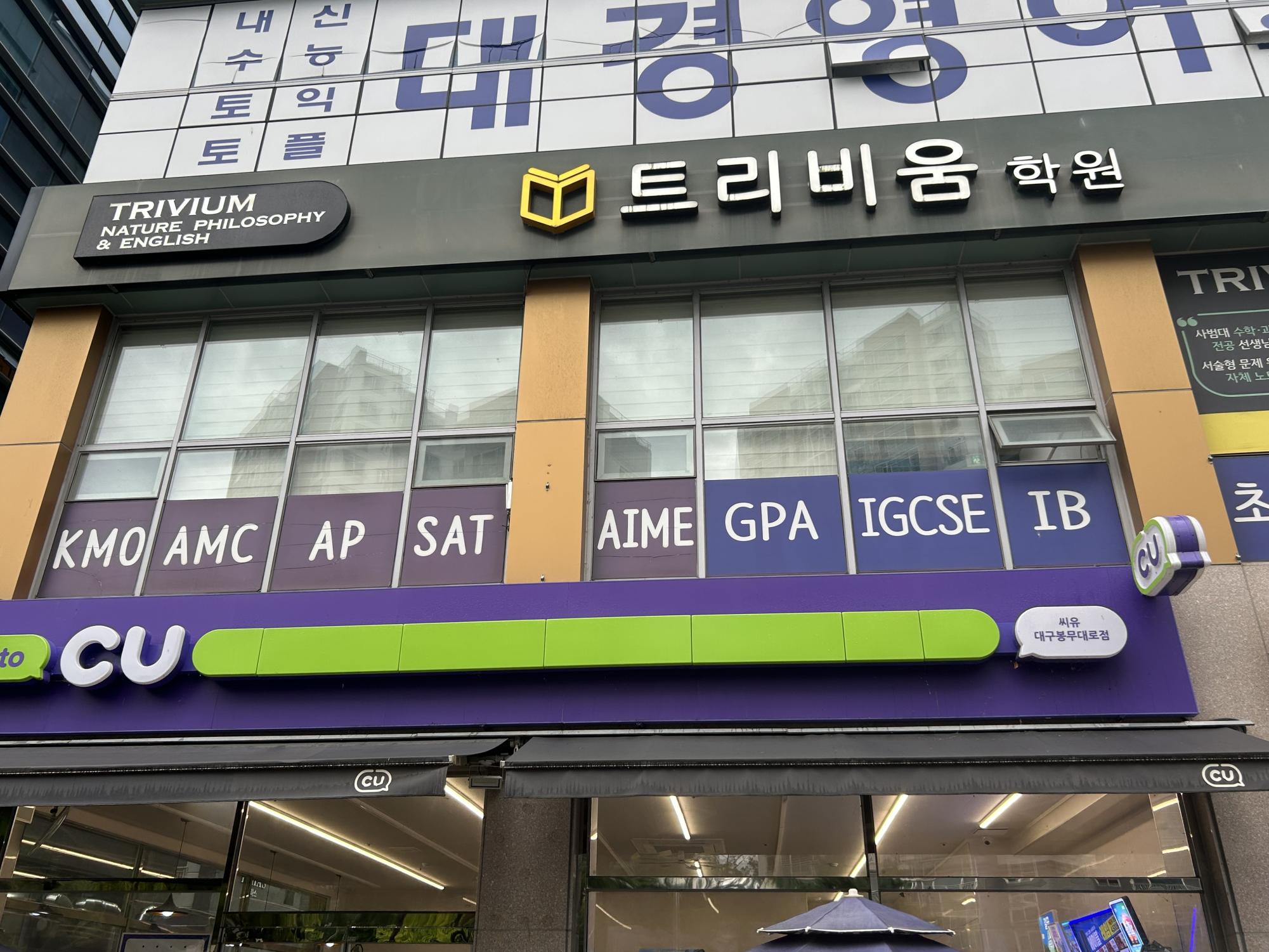

In the midst of summer break, students toil in the crowded classrooms of Gangnam district, where they study for upwards of eight hours a day instead of enjoying their hard-earned vacation. This reveals the harsh reality of SAT prep hagwons: institutions that overpromise an explosive increase in standardized test scores for a hefty fee.

These academies cost over thousands of dollars (millions of won)—one student paid $15,000 for an eight-week program. Mr. Kim, a former instructor at a prep hagwon, reported that these businesses cost “on average 50,000 won per hour”, with some charging “upwards of 80,000 won per hour.”

In the pursuit of marginally better test scores, South Koreans spend $18 billion, or around 20% of their household income, every year on SAT hagwons and private tutors. This figure increases annually. Locking valuable education behind a paywall severely disadvantages families with lower incomes, where financial troubles limit ambition.

A majority of SAT programs offer daily English prep classes during the winter and summer break periods, and classes often run from early in the morning to late in the evening. “Many students rely heavily on hagwons instead of self-studying”, said Sally Yun, a sophomore studying for the exam. “The pressure to attend can make them feel stressed”.

As students witness their peers toil for college applications, they feel a mandatory obligation to attend these institutions. “There is a lot of pressure because it’s competitive”, said Mr. Kim. “Everyone is trying to go to the top-tier universities, so they’re trying … to beat their colleagues. There’s a finite number of spots for universities, so … they are trying to do their best on the SATs. It’s almost expected to attend these SAT camps.”

Despite the many issues that surface, academies repeatedly report a correlation between attending their institutions and improved test scores, aiming to prove that investing time and money in test prep facilities can actually be worthwhile. “For the majority [of students], it did make a difference,” said Mr. Kim. “It’s just about constant exposure. When they get into the rhythm of taking tests daily, they can identify their mistakes quite easily and start figuring out … how College Board sets up their exams.”

Still, many find themselves repeatedly retaking the exam every cycle, unable to receive a satisfactory test score. According to the Education Resources Information Center, as many as 50% of test takers retake the exam every year, and some even retake it more than five times throughout their high school career.

While SAT is a rite of passage for most, excessive time investment on standardized testing take time away from other crucial parts of college applications such as extracurricular activities. Youth who study for eight hours a day or more become straight-A, 1600 robots with no real life outside of school. In the eyes of college admissions, applications containing no more than perfect GPAs and test scores often lack personality, which can turn years of effort into rejection letters.

Given its hefty price tag and questionable return on investment, students should instead turn to free online alternatives. “I do this online [course] where it gives me a bunch of questions that I can solve”, said Senior Minori Kojima. “It depends on the person and how they learn…but I think [SAT academies are] very overpriced”. Online programs such as Khan Academy offer the same support for a fraction of the cost and prevent the vicious cycle of SAT Prep academies.

As Yun said, “[SAT academies] can be helpful, but they’re not necessary.” Korean society must release the pressure valve of SAT prep, so that students can relax poolside, instead of laboring in hot, unwelcoming classrooms.

Jio Kim • Sep 20, 2025 at 5:05 am

Great drawing!

Volt • Sep 11, 2025 at 7:32 pm

Great to know about it. As an Eighth Grader I have to prepare for the SATs, but it is quite surprising that they pay about 20% of the household incomes. Also it was beneficial to know how SAT academies help us with our grades. Thank you for the article.

Elin & Chloe • Sep 11, 2025 at 7:31 pm

I do agree that students might need help or support to get better grades in their SATs or the IB tests, but I think the price for these prep academies are unaffordable for students. I also think that the students would be very stressed and anxious while studying for these exams, and the hagwons would burden them more with academic pressure.

GG • Sep 11, 2025 at 7:30 pm

Yes, I agree so much with this article- even though there are a lot of Korean students in my hometown, there are so many academies that have SAT preps as their course. I feel that the medical boards in Korea and America became so competitive, with everyone trying to go to the universities. I felt that the SAT scores and the GPA requirements for “good” universities are so high last Tuesday. Thank you for the good article!!

JakePark • Sep 11, 2025 at 7:27 pm

Great Drawing!

Mrs. Jolly • Sep 11, 2025 at 6:37 pm

Great article. I hope students/families will listen. You should have interviewed me as the SAT Coordinator:)

Jason • Sep 11, 2025 at 7:21 pm

frfr