Each tick of South Korea’s social clock signals imminent deadlines for marriage and motherhood, demanding that women obey tradition. This rigid paradigm equates divorce to a heresy that etches irresponsibility and incompetence into one’s identity in bold red.

Rooted in traditional ideals of family honor, Korean society often views divorce as a moral failure that leaves a generational stain; children of divorce become a justified target to face ostracism, judgment, and systemic discrimination. In a society that pathologizes divorced families and limits access to legal and educational opportunities, discussions remain shushed while judgment continues.

Korean divorce rates remained strikingly low for the past century, at 1.8% in 2024 compared to the 2.4% divorce rate in the US. This stark difference highlights not the security of Korean families, but a social stigma too stubborn to scrub out of the national psyche.

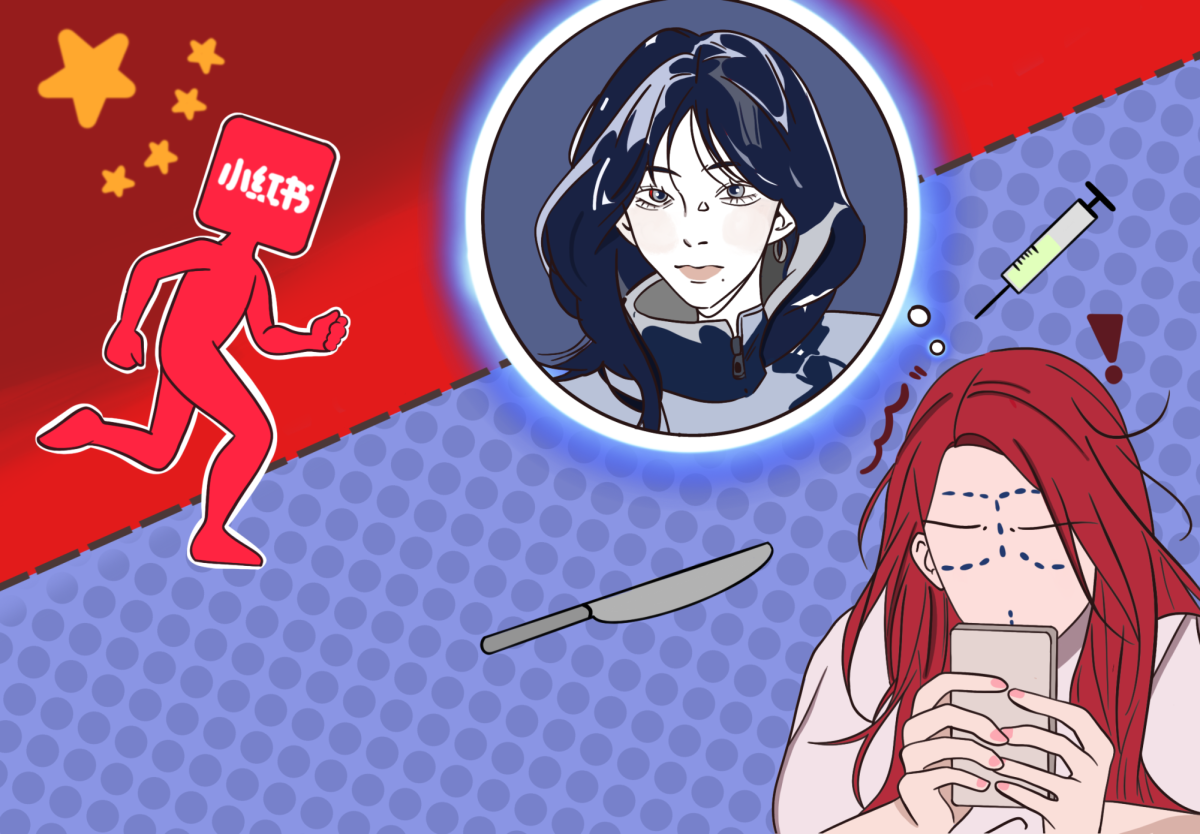

In recent years, however, what once remained unspoken began to move into public discourse. A media-driven wave shed light on a new perspective on divorce. Newly released K-Dramas like ‘I’ll Raise them Alone’ (내가 키운다), ‘Divorce Attorney Shin,’ and ‘Good Partners’ removed divorce from its taboo context and spotlighted realistic legal dilemmas and complexities of human relationships.

The Netflix reality series Love After Divorce amassed over a viewing time of over 57 million hours with the story of Korean divorcees who search for a second chance at love. The term ‘dolsing’ (돌싱), a Konglish abbreviation that denotes “returned single (돌아온 싱글),” played a pivotal role in this cultural rebrand.

Throughout the show, the camera zooms in on each individual rather than cold statistics. The production team emphasizes lived challenges such as discreetly gathering evidence of repeated affairs, enduring domestic violence to preserve their families, and giving up on divorce out of fear.

Harim Lee, a cast member of season 4, separated due to conflicts with her in-laws over religion. “My [religiously devoted] in-laws saw things through a traditional lens…It was this collision of old Korean culture and religion that made things deeply unfair in the position as a woman…Staying one more day in a life with someone behind this unbreakable wall would’ve meant losing myself completely,” Lee said.

Sora Lee, another cast member, said, “The more success I gained from my career, the more [my ex-husband’s] self-esteem dropped, and he hid my car keys so I couldn’t go out, made me believe I was overweight, through verbal abuse…I kept asking myself why I was living like this.”

Earlier divorce-themed shows revolved around dramatized narratives of divorce, adultery, and forbidden love. But Love After Divorce opens the floor for divorcees to voice their vulnerabilities free from stigmatization. It strikes the fine balance between authentic stories and viewer appeal to spin scrutiny into empathy.

A stream of “Dolsing” media followed Love After Divorce. Now, programs emphasize relatable conflicts and practical solutions rather than contrived, overly theatrical narratives. Thus, it helps destigmatize divorce in Korean society, normalizing remarriage and validating single parents. Today, 85% of Koreans find divorce and remarriage acceptable.

This shift highlights how the media rewires social norms by shedding light on struggles once obscured by prejudice. Amidst this cultural realignment, Korea inches closer to a society where stories that once hid behind closed doors attract public discourse and empathy.

Bonnie Kim • Sep 4, 2025 at 11:46 pm

This article made me reflect on my past thoughts that also held prejudice against divorce. At the end of the day, separation might mean a healthier life for both the couple and the family, and I learned how appropriate media coverage contributes to reduced stigma.

Volt • Sep 4, 2025 at 8:41 pm

I haven’t thought that K-content has got this big. Especially the program, Dolsingles has been programmed in the U.S. Thank you for new information.