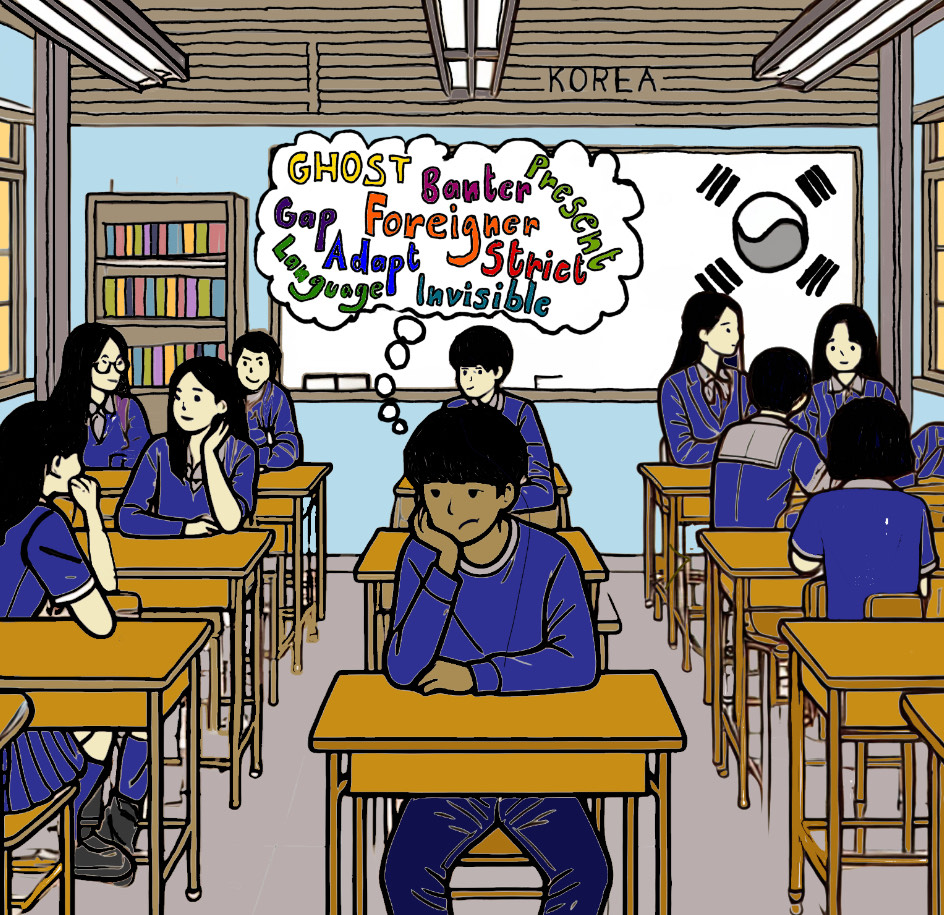

“I didn’t understand a single word anyone said. For months, I felt like I didn’t even exist—just there, but never really seen,” Tanish Kumar said. Being a foreigner in a public school proves challenging, especially in a country as homogeneous as Korea. Tanish’s earliest memories at Seobu Elementary School after the move from India are blurred with hushed giggles and scribbled notes passed between classmates—except him.

For many foreigners, studying in Korea comes with many hurdles, from language barriers to unspoken rules of group dynamics privy only to locals.

A decade later, Tanish and Thupakula Dharma Nagashree, another Indian in Gyeongsan Public School, remain the only foreigners in their respective schools. They make up 0.26% of Korea’s 5.8 million public school students. Now fluent in Korean, they effortlessly banter with their friends and handle Korea’s rigorous school system.

Although Tanish and Dharma feel included, they still perceive themselves as “outsiders.” Dharma, for instance, recalls her favorite memory, a school trip to Seoul, where she and her classmates stayed up until dawn, giggling over horror stories and sharing snacks. Despite the fun, she remains haunted by the fear that these moments of inclusion are temporary. “No one cared that I wasn’t Korean—we were just kids having fun. But sometimes I worry how long that will last,” Dharma said.

Tanish’s experience echoes that same tension between warm welcomes and isolation. While his background often sparks curiosity, it doesn’t always translate into legitimate bonds. “People are really friendly, and they love asking me questions about where I’m from. But when it comes to group chats or hanging out, I’m often left out. They’ll say it’s because I wouldn’t understand the conversation anyway, and sometimes that’s a good excuse—but it still feels isolating,” he said.

Aside from the implicit ostracization, foreigners also confront Korea’s rigorous education system, designed to prepare students for the College Scholastic Ability Test (Suneung) – a high-stakes college entrance exam that makes or breaks a student’s future. “A normal high school day ends at 10 p.m.. At first, I thought that it was insane to stay that late every single day just to study. But that’s how difficult the test is, especially since it’s all in Korean,” Tanish said.

Willy Wei, a 14-year-old Chinese student at Daegu International School, summed up the pressure at his previous Korean public school: “I loved my friends, but the system there was really tough. That’s why my parents moved me to an international school—to give me more opportunities to experience life outside of Korea,” said Willy.

Despite the academic rigor that leaves foreigners at a disadvantage, not everyone has the chance to attend an international school; for some, financial constraints rule out this option. “I don’t mind it here, but I want to go to the States to broaden my horizons… but international schools are too expensive,” Dharma said.

In addition to financial constraints, their fluency in the Korean language, rather than their mother tongue, further limits them from migrating to a different country. “At some point, it starts to feel like a trap. I only know Korean. I’m not very good at English or my native language. Even my thoughts are in Korean, so it’s hard to imagine me in any other place,” said Tanish.

This also creates gaps at home. “After living here so long, Korean has become my primary language. I struggle to express my thoughts to my parents, who can’t speak Korean at all, so I feel more alone at home. I’m farther away from my parents as I grow up because I can’t find the words,” Tanish said.

For students like Tanish, Korea offers a sense of familiarity—friends, routines, and memories that feel like home. Yet, that comfort also brings uncertainty about the future and where he truly belongs. “I’ve built a life here,” he said. “But what if I want more?”

In the end, foreign students in Korean public schools exist in an uneasy middle ground. They speak the language, follow rigorous routines, and form deep friendships. Yet, despite living like any other Korean student, they inevitably face their undercovered identity. As Tanish puts it, “Korea is my home. And I love it. But in this case, is there any other choice?”

Stella Park • Aug 23, 2025 at 9:38 pm

Interesting and inspiring alike… This article gives a perspective of how one might feel like in another\’s country. Very meaningful for so many.

Mr. Vis • May 8, 2025 at 5:34 pm

Thank you for opening this window of perspective for us, Niha. I found this article fascinating.