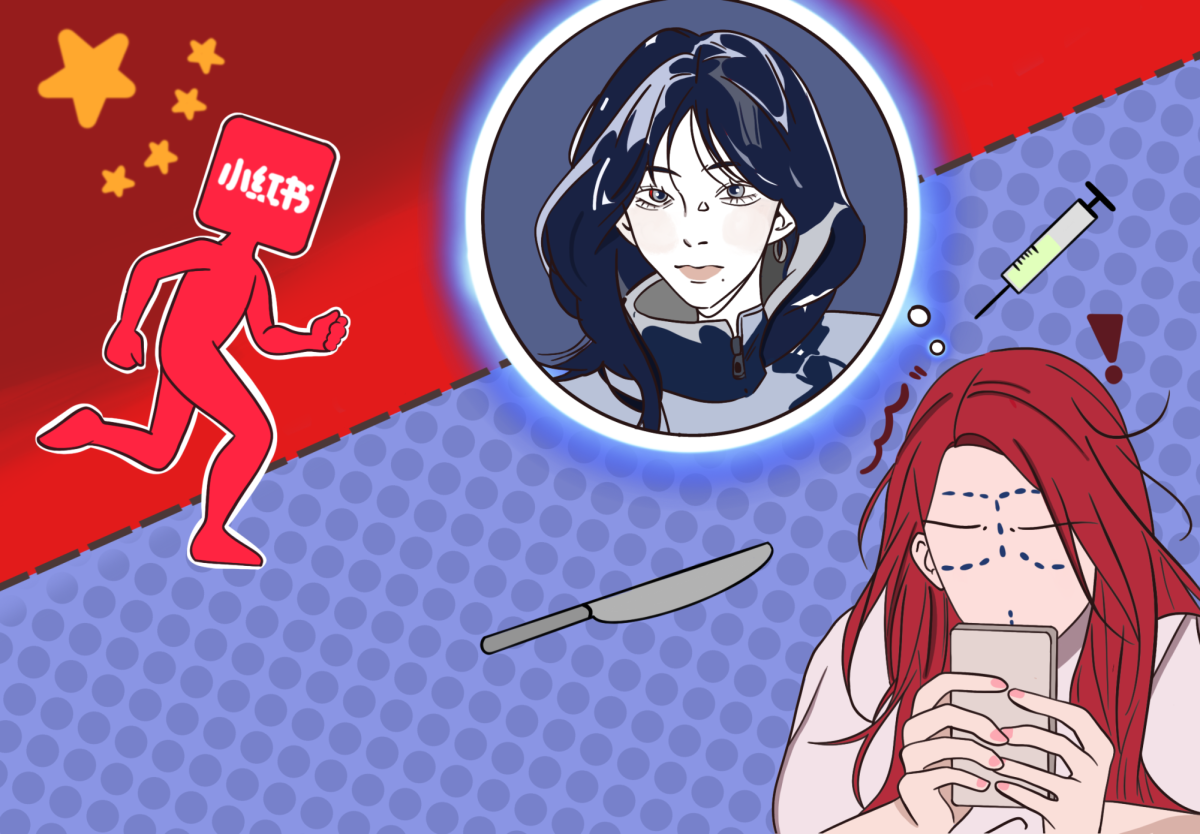

In Korea’s digital dining arena, delivery apps serve not just meals—but debt. Baedal Minjok, Korea’s dominant service platform, feeds a system where local restaurant owners grapple to survive while corporate profits soar. This cutthroat shift in the industry places restaurants in a dilemma between high app commission prices and alienation from the dominant digital consumer demographic.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Baedal Minjok saw its user base explode as the public faced heavy restrictions when dining out. Even with the restrictions lifted, Baemin’s grip on its customer base tightened—it now boasts over 25 million users and more than 30,000 restaurant listings.

Despite the appealing ease, the spurt in the industry created a cartel in the Korean dining market. At the heart of Baemin’s dominance stands its minimal delivery costs –– for users, that is. The mobilization of the free-service system redirects costs away from consumers and forces small restaurant owners to cover the gap through higher commission fees.

Haeyoung Nam, the founder of Café Dongee, Daegu’s local franchise, described how this predatory strategy drives restaurants to bankruptcy. “Baedal Minjok recently raised commission fees while maintaining its advertising costs [which owners pay to expose their restaurant on the platform’s website]. The free delivery feature raised a question: ‘Who bears this burden?’ To our dismay, it largely falls on the restaurant owners,” Nam said.

Nam quantified the difficulties Korean entrepreneurs experience when they utilize delivery apps. He said, “The commission fees exceed 20% of our profit margin—the pure profit for food businesses when selling a single meal is less than 20%.”

SunKyu Kwon, a kimbap restaurant owner, turned to Baemin out of necessity. “I started to use the platform since COVID-19 when a majority of customers avoided dining in,” he said. “Today, only two choices remain to take customers: offline or online. Baedal Minjok takes 7-10% of the 15-20% profit margin which is a lot. It really strains restaurant owners.”

Kwon emphasizes the unavoidable usage of online delivery platforms in the digital age: “The majority of customers use online platforms to order food. To make a profit, owners inevitably use a platform with the largest market share.”

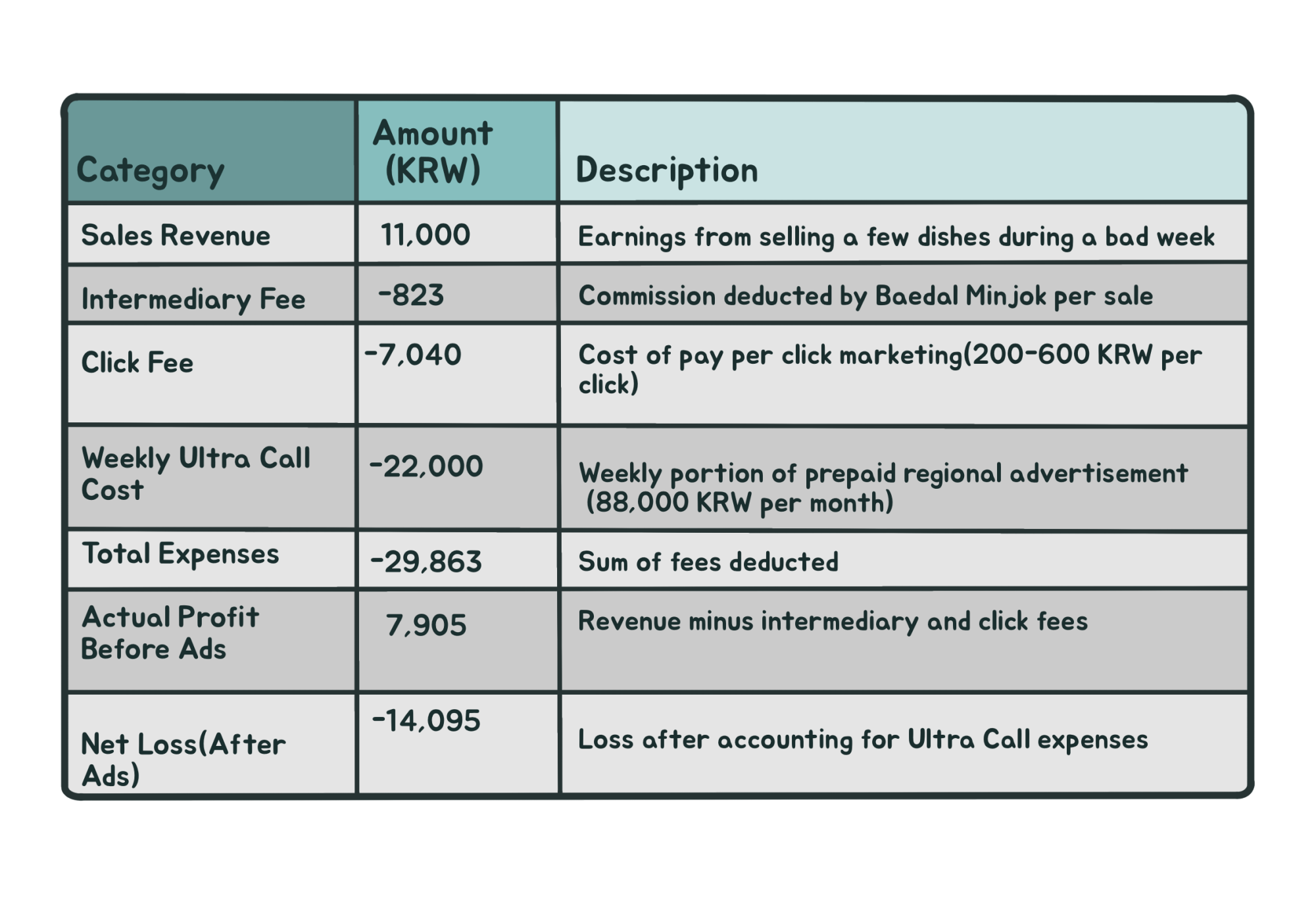

The kitchen-to-phone platform’s deliberate model leaves restaurant owners gasping for air. Baedal Minjok pitches its tools as growth opportunities, but they function more like traps. An internal advertising feature, “Click Our Store” (우리가게클릭), charges a cost per click (CPC) regardless of whether it leads to a purchase. Owners must bid for placement to appear higher in search results. Billed as competition, the scramble for exposure exploits owners’ desperation and leads to up to 3 million won in monthly advertising expenditure.

As owners cannot continue to run their business on losses, food prices rise and this drives waves of inflation. Thus, Korea’s economic crisis deepens and in turn traps businesses in a relentless cycle that pushes restaurants toward bankruptcy.

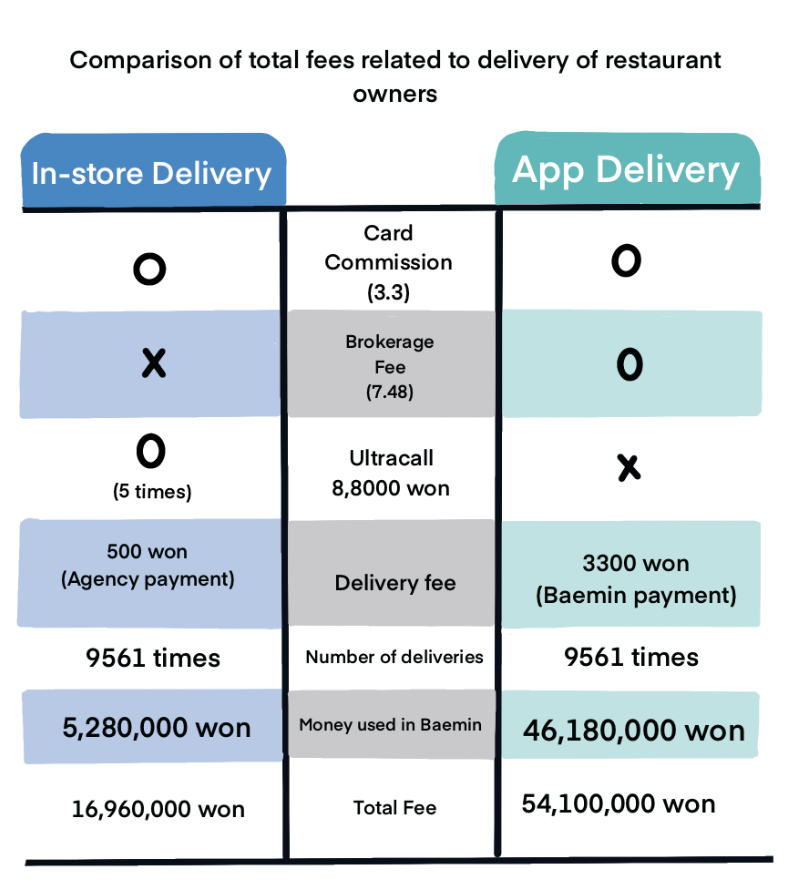

In response to increased commissions and opaque policies, the National Owners Association for Fair Platforms (공정한 플랫폼을 위한 전국 사장님 모임) boycotted Baedal Minjok’s free delivery service with an “In-store Delivery Day” where owners temporarily paused Baedal Minjok activity. However, with the app’s market dominance, such means of protest brought little change to the predatory market structure.

The financial strain on local restaurant owners runs deeper than just misleading advertising fees. The acquisition of Baemin’s parent company by Delivery Hero—a German delivery platform—further weakened Korea’s domestic economy; the money lost in the system funnels into the hands of a foreign corporation. A significant portion of Baedal Minjok’s profit—413 billion won, approximately $306 million, out of the platform’s total profit of 617 billion won — flows into Germany.

Regardless of the South Korean Fair Trade Commission’s (FTC) attempt to prevent a total monopoly, Delivery Hero still dominates 60% of the market. The absence of competition strips away any leverage for fair pricing and burdens consumers.

Baedal Minjok continues to take a heavy toll on local businesses, creating a vicious cycle of inflated food prices. As the dominant force in Korea’s delivery industry, it embodies the precarious nature of digital markets, where the interests of small restaurant owners fall on deaf ears of corporate giants.

The future of dining extends beyond the simple idea of food. It extends to the power dynamics underlying market control: who pays the price, who strips benefits from these progressions, and ultimately, who stays to shape the future market. Though delivery apps revolutionize gastronomy in the 21st century, the novel industry requires time and attention to put an end to the ‘hunger games.’

This wave of change hit global markets with its heat. US delivery corporations imposed strict clauses for restaurants to standardize dine-in and delivery prices. Most owners relied on increased dine-in prices to subsidize commission fees ranging from 13~40% of revenue which caused average restaurant profit margins fell to 10.1%. A group of enraged New Yorkers filed a lawsuit against DoorDash, Grubhub, Postmates, and Uber Eats for their monopolistic practices.

Jerome Kwon • Apr 24, 2025 at 7:26 pm

Great work! It’s very worrisome that Baemin is making it difficult for small businesses to run.