**Disclaimer: Some of the interviews featured in this article have been conducted anonymously to protect the safety and privacy of students and parents.

Inside cramped hagwon classrooms, kindergarten to middle schoolers, some barely tall enough to reach the whiteboard, tackle medical school-level coursework. Burdened with relentless expectations, they steel themselves for yet another sleepless night. This is the reality of Suseong-gu’s hagwon district, home to the nation’s second-largest private education market.

The continuous pursuit of medical school admission permeates everyone, from kindergarten students drowning in advanced coursework to high school graduates repeating the Suneung (수능) in a desperate bid. What once signified success now devolved into a high-stakes obsession. As the “Suseong-gu Rush” intensifies, it raises urgent questions about the costs—both personal and societal—of this unyielding race.

Often dubbed the “Gangnam of Daegu,” Suseong-gu has built a reputation for its intense academic environment. According to the Korean Society for Community Sociology, 10% of its residents have either recently relocated or remain in the district primarily to secure top-tier educational opportunities for their children.

The concentration of prestigious high schools has fueled this medical school frenzy (의대 열풍), as these institutions consistently send graduates to elite in-Seoul universities—a crucial launchpad for social and professional success in South Korea.

For instance, Gyeong-shin High School, located in the region’s hagwon district, recently received 75 admissions to elite medical schools. The school ranked first among public high schools nationwide in medical school admissions. “It’s not just about excelling—it’s about surviving. If you’re not aiming for medical school, you’re already falling behind,” said Junyeong Kim, a student at Gyeong-shin High School.

The rise of pre-medical school preparation classes further exacerbates this phenomenon. These courses—starting from kindergarten in the most extreme cases—illustrate the district’s single-minded focus on producing future doctors at all costs. “Parents enroll their children in these courses as early as elementary school. The mindset is simple. The sooner they start, the better their chances,” said Wonjong Lee, a pre-medical academy teacher in Suseong-gu.

As more kindergarteners enroll in these hagwons, the private education industry thrives, placing immense pressure on young children. Policymakers must act now to curb this madness and reassess medical school admission policies. Education should foster growth, not force toddlers into a rat race.

Likewise, this obsession stems from the desire for a stable future, reinforced by social pressures and a deep awareness of others’ expectations. In South Korea, success is often equated with admission to prestigious universities, securing a well-paying job, and achieving family stability.

Koreans perceive medical school as the most secure and socially respected path to achieving these goals. A mother of a middle school student in Suseong district said, “I know it’s hard on my son, but this is the only way he can have a future where he won’t struggle.”

However, this unrelenting academic pressure exacts a heavy toll. Late-night hagwon sessions, coupled with the expectation of unwavering academic excellence, have led to widespread reports of student anxiety, depression, and chronic sleep deprivation.

The erosion of free time and the ever-present fear of failure fuel academic burnout, leaving students mentally and physically drained. “It is a cycle of exhaustion, where the pursuit of success feels more like a struggle for survival than an opportunity for growth,” said Kim.

Yet, even after securing admission to top-tier medical schools, many students find that happiness remains elusive. During their grueling hagwon years, they believed that once they reached university, their struggles would end.

However, the reality of even fiercer competition and mounting academic challenges often leads to feelings of emptiness and lost youth. “One of my students recently ran away and suddenly quit [medical] school due to the overwhelming academic stress. I am sad and surprised to see how students who come into medical school these days don’t seem like they have motivation,” said a professor at Keimyung Medical School.

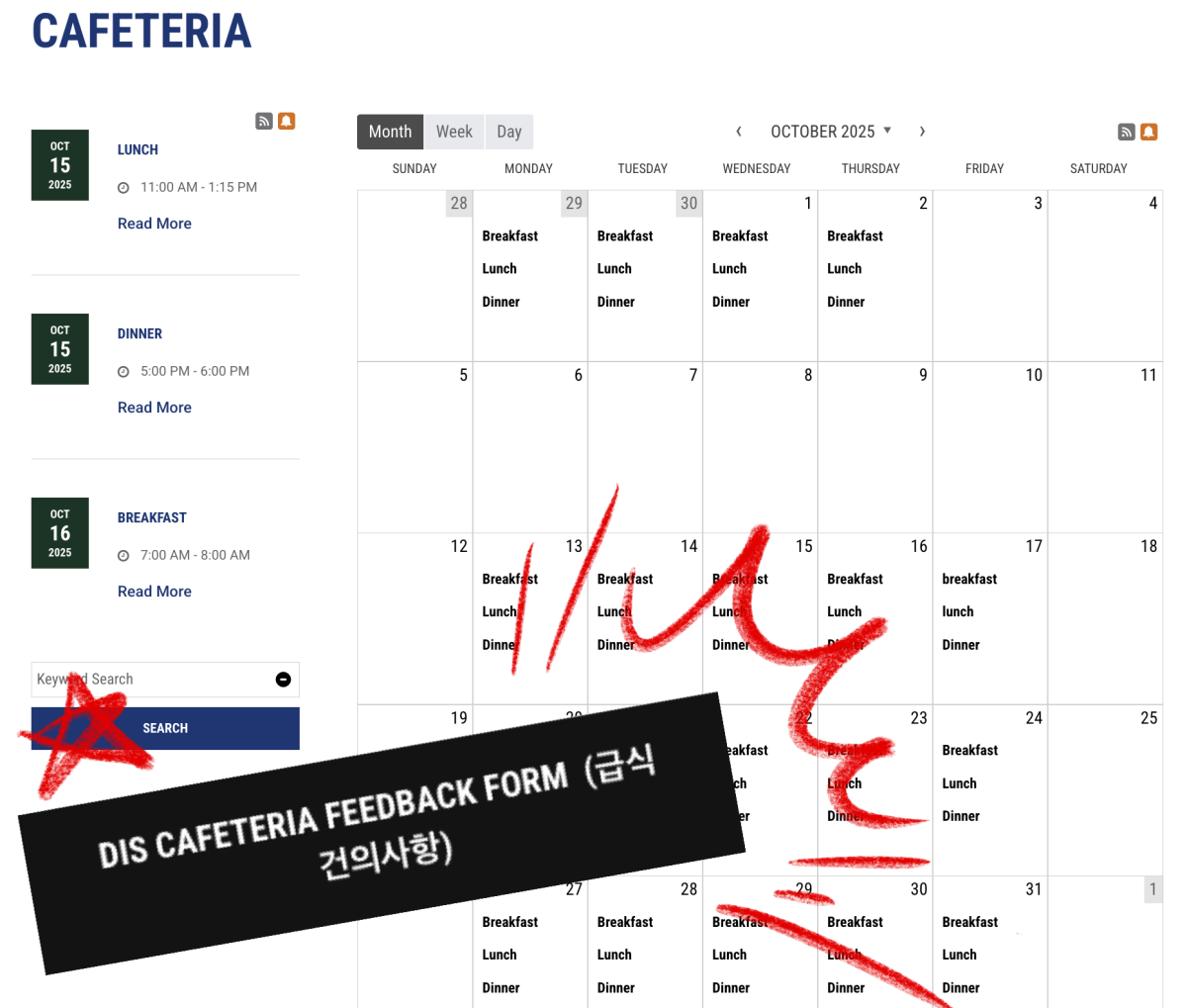

Furthermore, both financial investment and societal expectations fuel the rise of excessive competition in the region. Families pour astronomical sums into private education, often at the expense of financial stability, with some even taking out loans to afford the best tutors and programs.

The belief that securing a medical school seat is synonymous with long-term success has entrenched itself as an immutable social norm, making it nearly impossible for families to opt out without fear of their children falling behind.

Ultimately, the Suseong-gu phenomenon raises broader concerns about the direction of Korea’s education system. As families chase an increasingly narrow definition of success, the true purpose of education—intellectual curiosity, personal growth, and the cultivation of diverse talents—fades into obscurity. If the nation’s education system continues down this path, students will face the harsh truth that they sacrificed their youth for a future that was never truly their own.

L • Apr 3, 2025 at 7:27 pm

I hope students get some rest!