Tattered t-shirts, splintered straw baskets, and worn wooden chairs—all left behind as garbage—lie in decay in an unkempt yard. In Bansong 1-ri, a rural town an hour’s bus ride from Daegu, such sights lie scattered in abandoned homes along the local river. But this problem extends far beyond the confines of a single village. Across Korea’s countryside, sigols (시골), a growing number of undemolished empty houses continue to deteriorate.

According to a 2022 census conducted by the National Statistics Office, 19,397 empty houses sit in underdeveloped areas nationwide. Many of them have deteriorated to the point of collapse, yet they remain standing due to unclear ownership, high demolition costs, and lack of federal support. These abandoned structures depress property values and add pressure to already strained local governments.

For many residents, the homes aren’t just eyesores, but hazards that threaten the local community. “If you go straight down this road, next to the school, there’s a house that’s been empty for a couple of years now. It smells rotten when it rains and looks like garbage. Stray animals live inside it sometimes and kids dare each other to go inside like it’s a haunted house of sorts, which seems dangerous. We can’t tell what’s happening there. The fact that homeless people could move into it is also a concern,” said Bansong 1-ri resident Park Chun-ja.

Abandoned homes also facilitate illegal trash dumping in the area. “Last year, someone started using an old house near the stream as a trash site. They dumped furniture, a broken TV, and even bags of everyday trash. We called the local office, but we had to wait for months and months to eventually get a warning sticker. So in the end, some people in the village helped clean it up and lock the doors,” said Park.

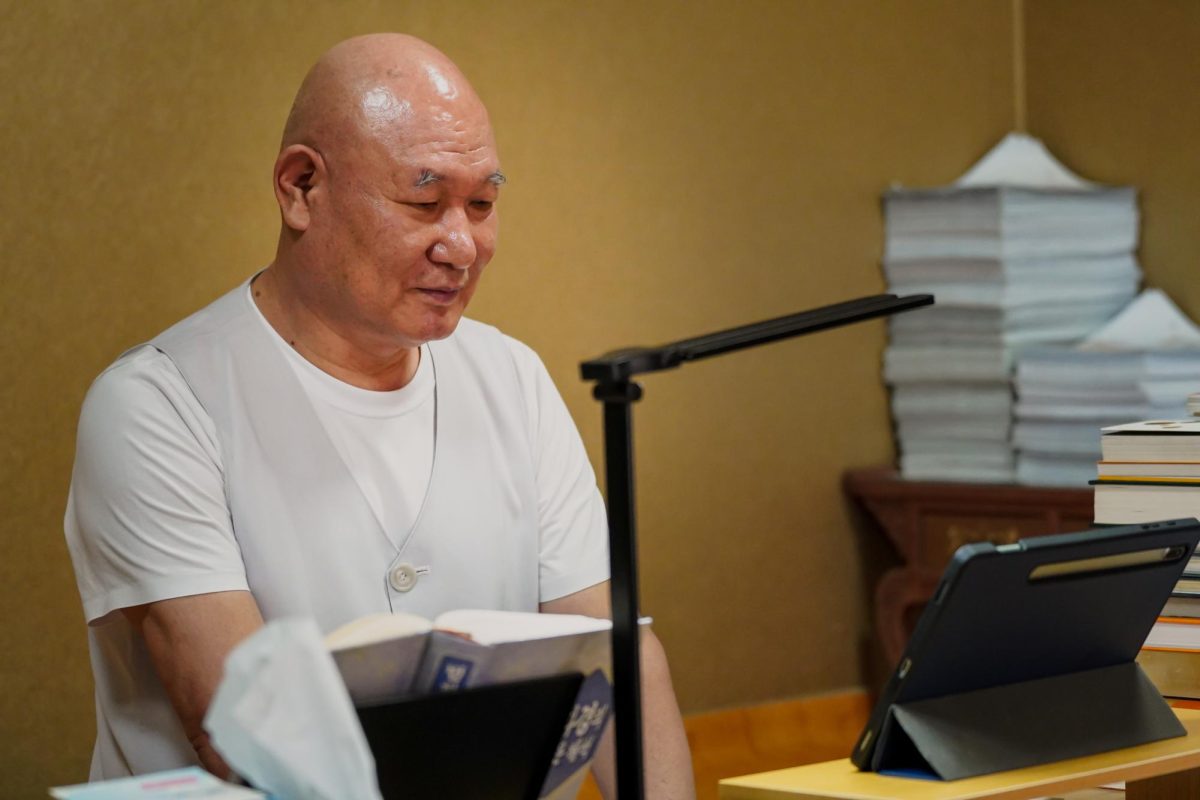

Local governments attribute limited budgets to the lack of redevelopment. “With how common it is, it’s only natural that many complaints are brought up about these abandoned buildings in the community…They wanted the government to tear down the structure and redevelop the land, but the reply was that funding simply wasn’t there,” said Kwang Sangcheol, another resident of Bansong 1-ri.

Even when budgets allow, complex legal procedures delay demolitions. “When residents pass away, it’s customary that many of their properties are given to their children or family members…the government can’t legally touch the building unless they get the inheritor’s permission, and tracking them down takes a lot of time. Many of them live very far away…reaching them and getting their permission is difficult,” said Kwang.

The average cost of demolition for a rural home totals around $13,000, due to asbestos removal (a once-popular building material, now known to cause chronic lung disease) and waste disposal driving up costs. Additionally, the current law often increases property taxes when an old house is demolished and classified as vacant land. While government subsidies may help, many owners still hesitate due to these concerns.

In a few cases, local authorities step in to remove high-risk structures. “One property was finally demolished last year but it took more than four years for it to happen. It was nearly on the brink of collapse and was infested with a wasp nest… It’s a relief that demolition does happen, of course, but we can’t wait that long for every single place,” said Kwang.

Now, newly implemented federal programs encourage voluntary demolition. The national government recently announced new subsidies of up to $7,000 per demolition and mitigated tax charges for landowners who agreed to demolish vacant structures. However, its uptakes showed little progress. In a recent survey, only 1.2% of owners contacted by local officials agreed to clear their properties.

Despite these setbacks, local residents remain hopeful. “If we could convert a few of these empty plots into gardens or gathering spaces or even just sell them, it would make the whole village feel so much better. We’re not asking for much—just clearing out the worst buildings so the rest of us can breathe…this is the last thing we should be worrying about,” said Park.

Yet, a quiet resilience remains among the decay. Residents continue to sweep their porches every morning. Others still hang their dried peppers on string lines under the sun. In the towns left behind, they wait—hoping that their community will someday return to its once-thriving past.