*One interviewee wished to remain anonymous due to privacy concerns

In front of a judgmental crowd of iPad kids, Kim nervously pulls out a notebook from her backpack. Others sneer and call her cheap and poor. Without the latest gadget, Kim feels inferior. This is the reality of a so-called “Dirt-Spoon” (흙수저) in 2025.

K-dramas, powerful mediums that shape cultural values, often show characters that embody extreme wealth. The casual yet loaded inquiry “너희 집 몇평이니?” (“How big is your house?”) exposes an underlying hierarchy. Children absorb these messages and start to internalize that financial status defines their identity and worth. When these figures flaunt luxury and privilege, young viewers normalize such behaviors and compare their lives to an unattainable standard.

“I used to get bullied for not owning an iPad in my class. Everyone else had at least an iPad or a MacBook, but I was the only one with just a paper notebook. So, I would always be teased and called poor. I felt like I was the one weird and wrong,” third-grader Go-Eun Kim from Dongdo Elementary School said.

On social media, users scroll through curated content that features the lifestyles of “gold spoons,” with extravagant homes, luxury cars, and exclusive hauls. Meanwhile, the “dirt spoon” lifestyle often reinforces negative stereotypes like “Dirt spoons don’t have friends” or “Dirt spoons can’t make any relationships.” These platforms create an environment where wealth becomes desirable.

The concept of elite school districts, such as 수성구 (Suseong-gu District), 강남 (Gangnam-gu District), and 대치동 (Daechi-dong), broadens the disparity. “Many don’t realize that everyone gets a different level of education and most people look down on others’ ability to work based on their economic status. Some people would say, ‘You’re dumb’ to others that did not go through the same SAT prep they did in Apgujeong or Daechi District,” an anonymous DIS alumni said.

The implications of Korea’s spoon hierarchy extend to bullying. Kids who lack the latest gadgets or live in less prestigious areas often get bullied, not judged by their character but by their possessions. “At DIS, people would judge each other by the shoes they wear. Even if you’re not close with that person, they would go around telling other people about your economic status. Some would search online to check how much my hoodie, jacket, and glasses cost and ask if my products are fake,” the alumni said.

The impact of Korea’s spoon hierarchy extends beyond playground politics. It creates a culture where these disparities determine opportunities. Kim said, “There was a group project where we were supposed to divide into groups of 5, but no one wanted to be in the same group with me because they thought it would be hard for me to communicate with them since I didn’t have any electronic gadgets. So, I felt very isolated, and I really wanted to quit school at that time.”

As the technological world permeates into younger generations, devices like laptops and iPads become status symbols. Students without access to these tools face exclusion, not just from group activities but also from the broader social fabric of the classroom. Teachers, while often well-meaning, inadvertently exacerbate the issue by designing assignments that heavily depend on digital access, and sideline those who lack it.

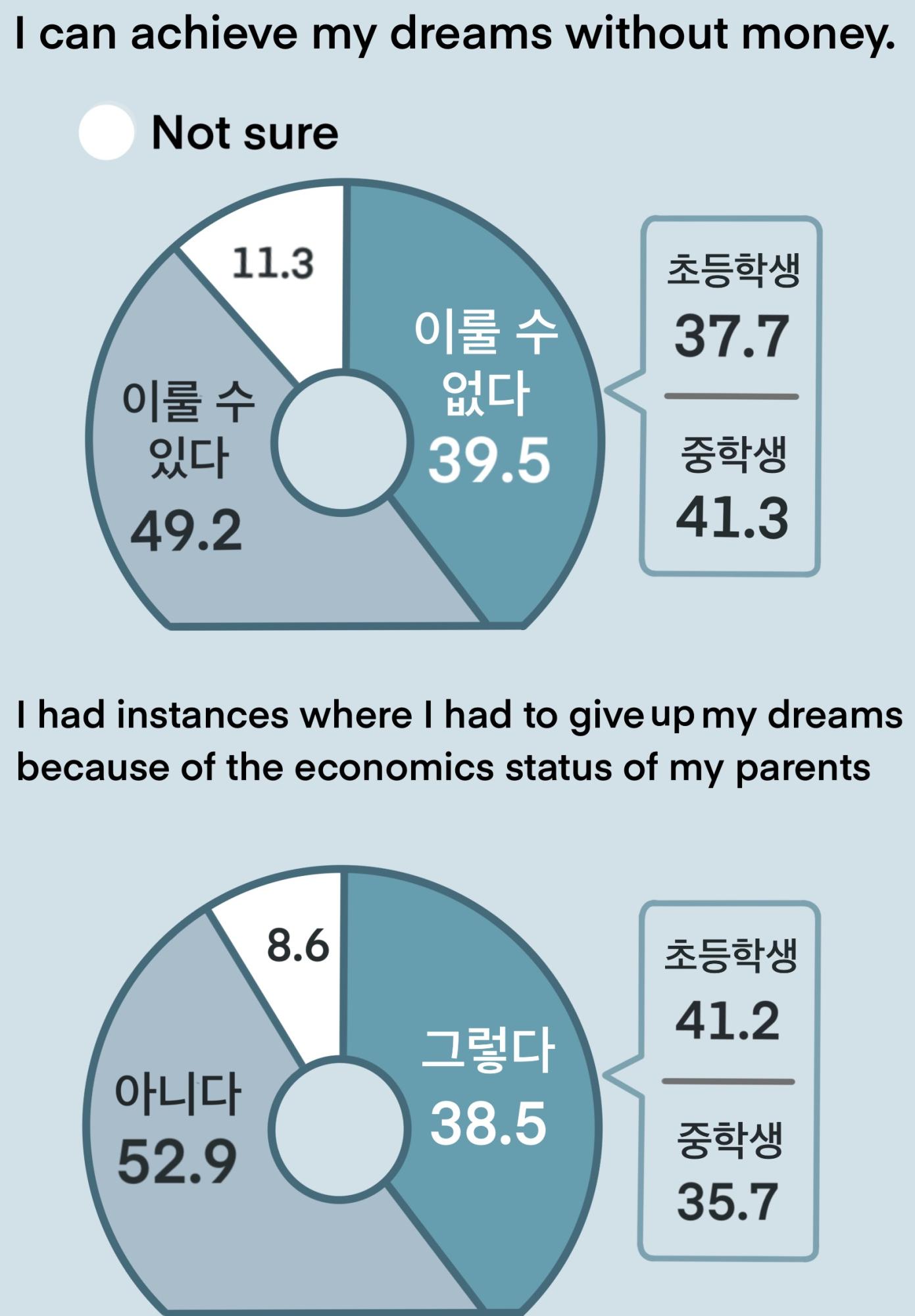

Korea’s “spoon hierarchy” highlights the deep divide caused by materialism and socioeconomic disparities. Tackling this issue requires collective efforts from schools, families, and society to foster equality and understanding.