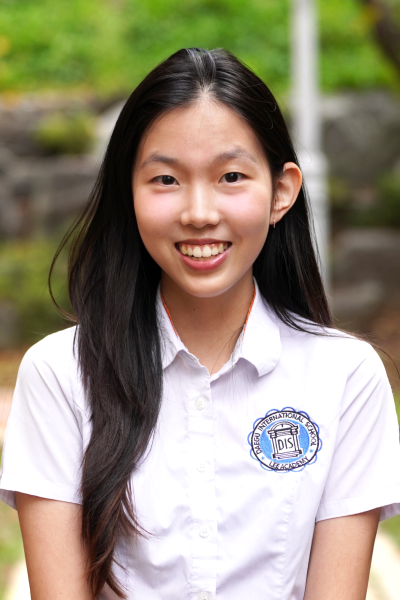

Under the mask of Azul Rivera: a young fencer’s leap of faith

Beads of sweat roll down freshman Azul Rivera’s forehead as she lunges forward, sword in her hand, ready to attack. Her aching limbs scream to stop, but she pushes through until she sees the green light flash on the scoreboard, a point to her name. When she lifts her mask to cross swords with her partner, her eyes sparkle with joy that she has triumphed over yesterday’s self. Even gruff Coach Lee, famous in the fencing club for his tough love, can’t help but flash a smile at the young athlete’s passion that brought her halfway around the world from Vancouver, Canada, to Ulsan, South Korea.

11-year-old Rivera never expected she would fall in love with fencing, let alone pick it up, during her time in Vancouver, Canada. “I didn’t want to do fencing because it’s not a well-known sport. But there is this really famous Mexican fencer [who] won a silver medal in the Mexico Olympics, and she was my grandmother’s role model when she was a kid. My dad convinced me that it would make my grandmother happy. My grandmother always believes in me, and I wanted to make her happy, so I went to the first practice,” Rivera said.

It took only a handful of practices for Rivera to fall in love with the sport. “Fencing is competitive, but it only happens when you’re on the piste. Off the piste, it’s a whole different story. Just the feeling of wearing the gear, holding the sword in the starting position, and fencing is the best feeling.”

With her mind set on the sport, Rivera trained arduously to rise from an underdog to the top dog of her club. “There was this girl who was way better than me, and my goal was to beat her,” Rivera said. “At my first fencing competition three years ago, I won a bronze medal. It was the only medal my club won, and that made me go on.”

However, insurmountable circumstances separated Rivera from the beloved piste. “My coach got fired because the lead of the club,saw the parents were more interested in her than in him,” Rivera said. “He told her that she was stealing students. So he just fired her out of jealousy.”

Consequently, Rivera’s coach had to start from scratch. “After she was fired, I was her only student, but I really wanted to do it, so while she got a club and all the fencing gear, we trained in my apartment’s yoga room. But I couldn’t spar with anyone and eventually, the head coach kicked me out of his club because he told me I had to choose between him or her, and I started losing interest.”

Rivera returned to the piste with high hopes, but fencing felt foreign to her after a six-month hiatus. “When I came back for a month and a half before going to Korea, I lost my stamina and I didn’t have the same speed, because in those, like six months, training only once a week, I couldn’t keep the same stamina, the same speed, the same movements, even,” Rivera said. “I thought I would come back and win everyone, but when I came back, my speed was bad. My stamina was bad. Everything was bad.”

Thanks to her family’s support, Rivera persevered until an opportunity drew her out of her slump. “My dad always supported me, and he told me, “‘Keep doing it. You won’t gain back your speed, your stamina, everything in a week or in a day. It takes time, it takes dedication, it takes perseverance.’ Then, my coach told me, ‘Why don’t you go to Korea for a summer? I think you’ll like it more, and your mind will be only on fencing,” Rivera said.

Within a few weeks, Rivera traveled 8,191 kilometers to Ulsan, South Korea, the #1 fencing nation, to spend the summer training. At the end of the summer, she made up her mind to move halfway across the world to train. “When I came to Korea, I loved the way of training: just seeing the boys and girls, especially the girls, amazed me, and I thought, ‘Maybe I could fit in with them, because if they’re determined and I’m determined, it’s a good match. I wanted to be at the Koreans’ level, and I had a goal to beat.” Rivera said.

Her family got on board right away. Marky Rivera, Azul Rivera’s mother, said, “I saw her determination. She was the one who chose this life, and she really wanted it. We want her to be what she wants to be, and our job as parents is to support, to give our best for our children. So when she said, ‘I want to go to Korea, we said, ‘Okay, let us see if we can do it.’”

However, the Rivera family struggled to find a school that would accommodate them until they stumbled across DIS. “The process of finding a school was very hard because my parents don’t work for a Korean enterprise. [The schools] assumed that I came to Korea with one of my parents working for a Korean company,” Rivera said. “But the DIS admin, especially Ms. Leah, managed all the immigration things, convinced the government, gave the letter of recommendation, and helped us find a real estate agent. She was like an angel.”

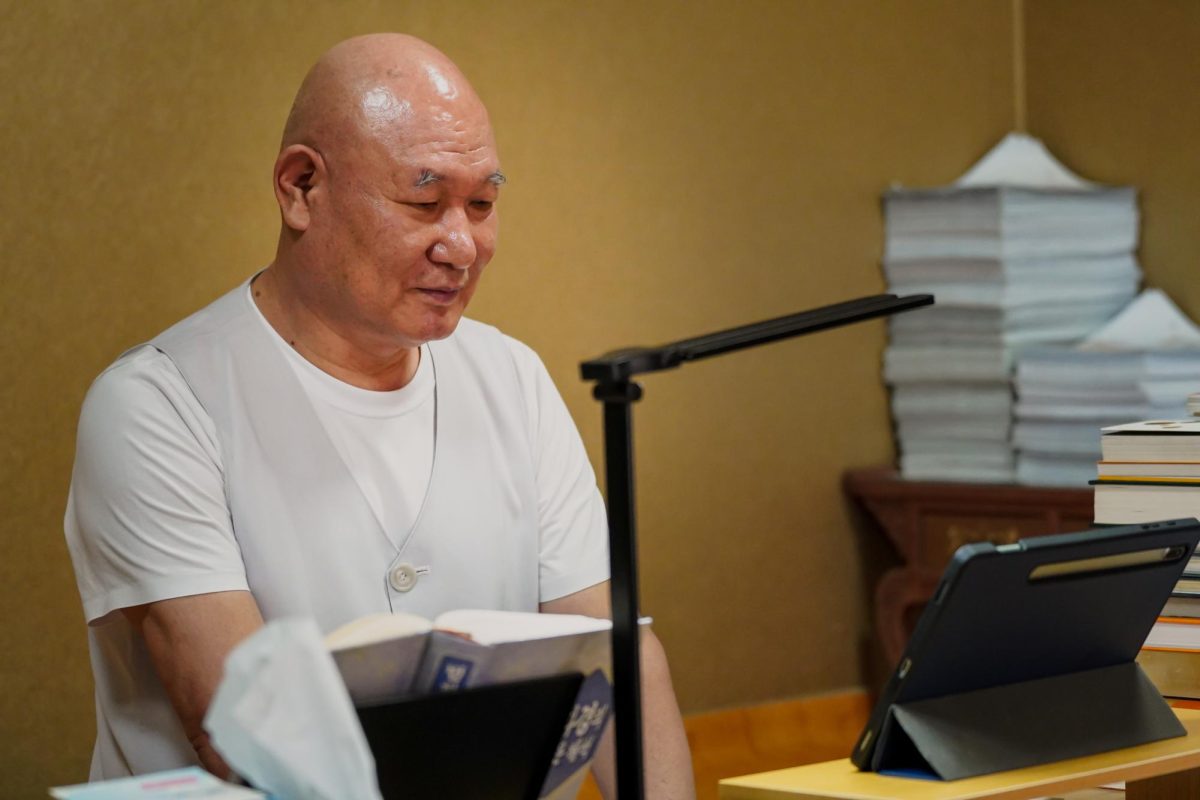

Now, Rivera hops on the KTX four days a week for a two-hour journey to her training center in Ulsan, where she trains with Coach Lee, a former fencer for Team Korea and a coach for the city’s fencing team. Despite her three-year-long career, she started clean. Rivera said, “My coach is starting me again from the basics because he wants me to have the basics really good, and then I can move on to harder things.”

On weekdays, Rivera tirelessly drills techniques to prepare for Saturday, when she steps onto the piste to spar with her clubmates in her age division. “On Monday, Thursday and Friday, I arrive at 6 p.m. at the gym. And there I warm up for 30 minutes. I do stretching. I run a little bit. I gear up just my glove, my sword, and my mask. And I start doing one-on-one with my coach from 6:30 to 9 p.m.,” Rivera said.

At the end of the week, she finally gets a chance to spar with her clubmates. “On Saturdays, we warm up for five minutes, and then we gear up and start fencing straight from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m.,” Rivera said. “Right now, I’m just fencing with the middle school boys and girls. Among the girls, I’m in the middle – not the best, but not the worst.”

Contrary to her Korean clubmates, Rivera chose a slower path. “When I was making plans with my coach, he asked me, ‘Do you want to get beaten or not beaten?’ Because if you get beaten for your mistakes, it takes two years to complete the whole program. But if you don’t get beaten, it’s an extra two or four years,” Rivera said. “I decided not to get beaten because I’ve never been hit in my life, and I’m used to working hard, being determined, and setting my mind to it.”

During her time in Korea, Rivera also faced language barriers with her coach.“My coach shouts a lot because he gets frustrated that I don’t understand. Yesterday, he was telling me that when I go in to break the distance from my opponent, I need to get their arm out for them to attack me so I can get the point right away. But I didn’t understand how to do it. We spent 30 minutes. He was screaming, and I didn’t get anything,” Rivera said. “But when I finally did it, he said, ‘Oh my God,’ and we just started laughing.”

Although she has yet to rise to the top, Rivera accepts it as a challenge to overcome rather than an insurmountable obstacle. “Right now, I’m not the best in the club. But I don’t find it discouraging. I think, ‘No I’m going to win them. I want to be better than them,’” Rivera said. “I want to beat them – middle school girls first, then middle school boys – because I’m not satisfied with where I am right now.”

She added, “With fencing, you can be number one for one day, and on the next day, someone else is number one. But when someone beats me, I don’t get mad. I become determined that the next time I face this person, I’m going to beat them by a really large margin. I set my mind to it, and I do it.”

Rivera’s determination stems from her childhood and family. Marky Rivera said, “The day that I was proudest was when she didn’t get what she wanted, but she kept her determination and said, ‘Okay, right now I didn’t do my best, but I will do it.’ Because when you are happy, everything is so easy, but when you experience failure and get back up, that’s what brings out the best in you.”

Her family’s unwavering support keeps her motivated, despite the four-hour commute time and arduous training. Every practice, Rivera’s mother or father accompanies her on the journey to and from Ulsan. “Of course, it’s tiring. But Azul, her dream, motivates me, and I am not going to be an obstacle for her to accomplish it. I am giving her all the opportunities, all the facilities, so she can focus on her dream and make it a reality.”

Now in a new country, the Rivera family puts their daughter first. “I always say, ‘Okay, if you want to do that, perfect, but you have to enjoy it. You have to be happy. The moment that changes, and it becomes a must, that’s a no.”

With endless determination and support from loved ones, Rivera’s eyes continue to light up every time she steps up on the piste. “In 10 years, I see myself hopefully in the Olympics. I want to go to the Olympics for Team Mexico,” Rivera said. “Until then, I’ll keep telling myself, ‘Don’t give up. It’s a hard path, but I can do it. Don’t give up.”

Kyla A. • Dec 5, 2024 at 6:29 pm

Great article! Also, Azul you’re good at both drumming AND fencing?! THAT is talent.

Steven • Dec 5, 2024 at 6:26 pm

Looks very cool

Michelle Doh • Dec 5, 2024 at 6:25 pm

omg azul slay

Enrique y Dalhid • Dec 5, 2024 at 3:47 pm

Felicidades Azul! Our best wishes always, keep going, champs will always be remembered 🙂

Yura • Dec 4, 2024 at 6:38 pm

Azul is so mentally determined but her passion it’s amazing

daniela rivero • Dec 4, 2024 at 9:31 am

Congratulations Azul, from Mexico!! What great support from your parents and what great effort and dedication from you!! Greetings with love

Sola • Dec 3, 2024 at 11:35 am

This is awesome!!!!! Welcome to DIS :))