Guard Your Country, but at What Cost?

High Schoolers at DIS on the K-Military Mandate

November 9, 2021

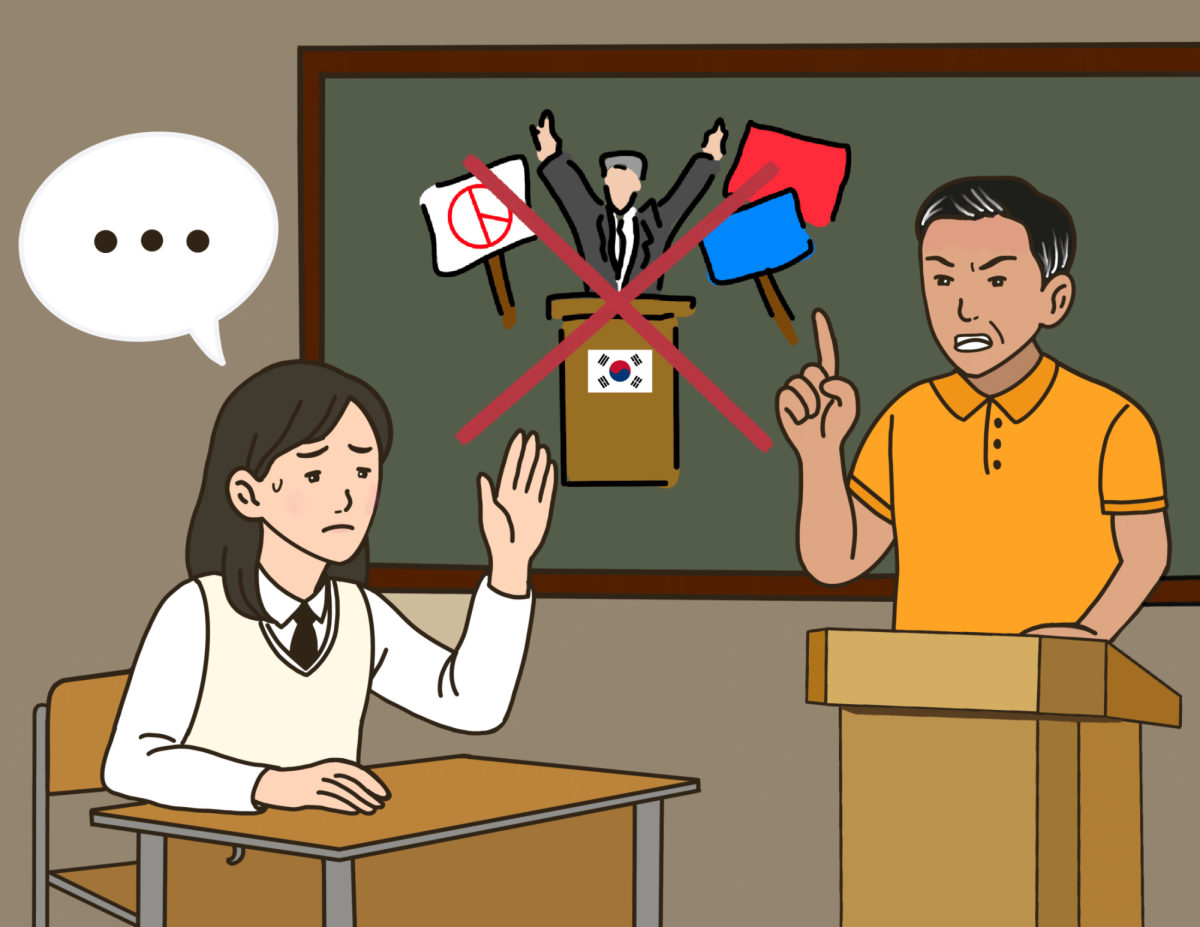

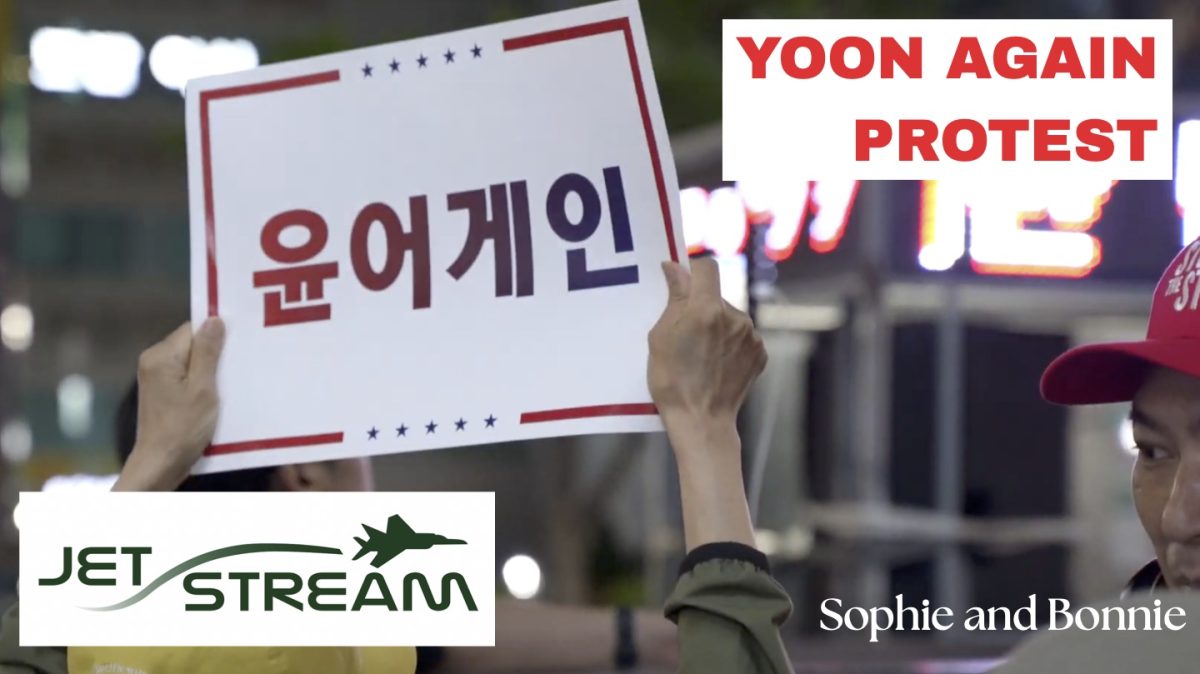

“All citizens shall have the duty of national defense” is firmly stated in the 39th article of the Korean Constitution. Because the Korean peninsula is still technically at war, a military mandate is still being enforced for men between 18-28 years. When a Korean male becomes 18 years old, he is tested on his compatibility for military training. Based on an evaluation of his educational background and physical abilities, he is graded on a scale from 1-7. According to that grade of “fitness,” he will be assigned to either active duty, a social service agency, a second militia service, or exempt from serving.

On the other hand, those who possess multiple nationalities get to choose whether or not they want to keep their Korean citizenship — and with it, their duty to guard the country. As the majority of DIS students plan on studying abroad after graduating, Korean dual citizens are torn – are they willing to keep their Korean citizenship and be enlisted, or will they continue everyday life while denouncing their Korean citizenship?

When asked whether or not he will forfeit his Korean citizenship to avoid military service, senior Noah (who possesses dual citizenship for Canada and South Korea) stated that he “would eventually need to go to the army, since I want to come back here, even if I study and work abroad.” Noah also added: “I’ll probably be categorized at grade 4 because of my scoliosis, which means I would serve as a social service agent instead of going to active duty.”

Freshman Ethan, who is a Korean-American, voiced that he would drop his Korean citizenship: “I think getting U.S. citizenship is better. I heard there are more advantages.” Ethan acknowledged that “the lingering idea of having to serve in the military did influence me in that decision. Since you have to stay nearly two years in the army, it would take up a lot of my time, and it could be a hindrance to my career and studies.” Interestingly, Ethan stated that “If I were exempt from forcefully serving in the military, I think I would’ve considered the issue more. I’ve lived in Korea for such a long time that I might have wanted that citizenship. But in the end, I think I would still prefer American citizenship because of the better school and education systems in the States.”

Eugene, a 9th grader and dual citizen of the United States and Korea, answered that he plans on nullifying his Korean citizenship in the future. He justified: “Mostly because I’m planning on being a doctor, and 2 years of military service could really slow down my career; medical school takes up a lot of time in itself!” The freshman revealed that without the military mandate, his choices might have changed: “If I didn’t have to serve, I would’ve chosen to keep my Korean citizenship.”

Although there have been a few improvements in the Korean military, many Korean men still feel disillusioned and unfairly treated by the system. Many men are hesitant about sacrificing what two years of their youth could entail — academic and professional opportunities, improvements in life, and the freedom of youth could be damaged. The job market and university applications are both growing tougher every year, and serving in the military is a setback for career and degree-seeking men.

Despite the varying perspectives on their dual citizenship situations, it can only be acknowledged that the army plays a crucial role in influencing their future plans. But rather than a patriotic opportunity to serve the country, most see this experience as a major roadblock.

Justin Huh • Nov 11, 2021 at 1:07 am

I would rather get a US citizenship so that I don’t have to serve in the military.

Nice Article!