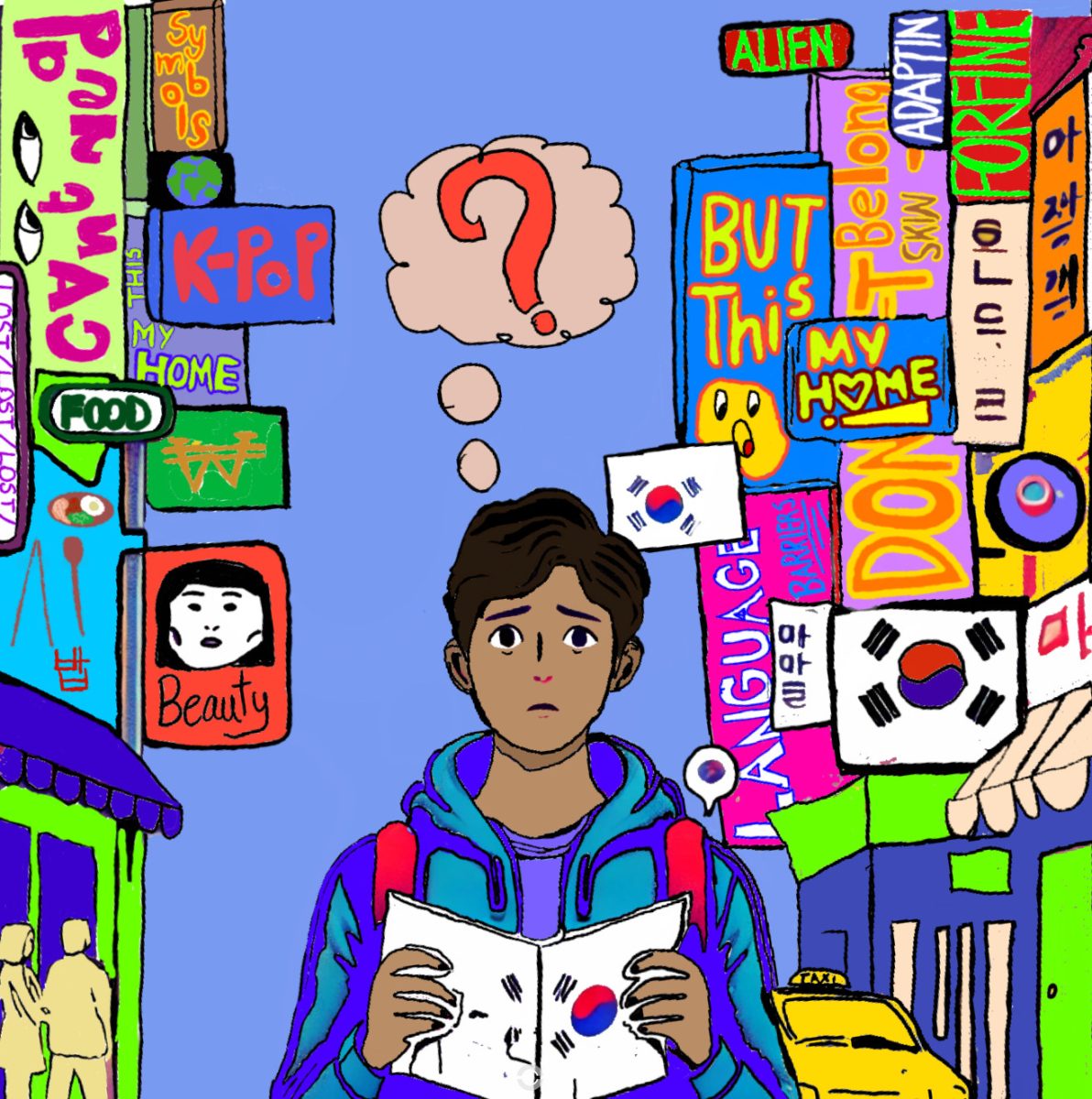

When I first strolled down the bustling streets of Daegu, the air came alive with vibrant noises: vendors shouted across the market, the unmistakable beats of K-pop blasted loudly from every corner, scents of Korean delicacies wafted into my nose, and the streets buzzed with the hum of everyday life. But then, as I took another step, the world seemed to hit pause. Unlike in India, the chatter around me faded into hushed whispers like “외국인이야?” (“Is that a foreigner?”) and “여기도 외국인이 있네?” (“Oh, foreigners exist here too?”). With every step, I felt like an alien on display.

But over the years, Daegu—and Korea as a whole—became familiar with the diversity of foreigners. Even K-pop started to contain a Western touch. I still chuckle at how a passerby 할머니 (grandmas) used to call me 예쁘다 (pretty)—probably because I looked different—and slip me some money. Those truly felt like the best days! But today, fifteen years later, my sister doesn’t receive the same treatment. Foreigners just aren’t a big deal anymore.

Evolutions of Interactions

As a child, I failed to recognize numerous truths that now seem evident. As junior Sankeeth Udayakumar, an Indian student, said, “When I was small, I didn’t really notice much. But now I can see it because I’m basically a wise old kid now.” The older I get, the more I notice the barriers, the unspoken boundaries that mark you “different,” no matter how long you’ve lived here. People here show great kindness (정), but because of the language barrier, they tend to keep to themselves unless you make the first move.

Life as a foreigner in Korea for over a decade offers a unique lens into the country’s cultural evolution. Previously, a simple taxi ride felt like an adventure, as many drivers hesitated to pick up foreigners and said “안 돼” (no) the moment they saw us. Now, foreigner-friendly apps like Kakao T are superheroes without capes.

Hospitals too stand as a testament to Korea’s transformation. In the past, if you didn’t speak Korean, you felt more like an inconvenience than a patient. Today, many hospitals offer English-speaking staff, and translation apps to expedite the process.

Back then, I often flapped my arms like a madman just to get the point across. My family carried around massive, 3-kilogram, hard-copy translation dictionaries – bricks of paper we hauled from place to place – which turned out to be an epic fail. Most of the time, we would give up on the hassle and return to the good old hand-flapping method.

Thankfully, I don’t need to do so anymore, as more people speak English now. “Back then, it was almost like they expected foreigners to be completely clueless. Now, you can get by with Google Translate, but back then, we had these clunky old translation devices that barely worked,” junior Minori Kojima, a Japanese student, said.

Social Challenges

Despite the growth of multicultural societies in Korea, the feeling of an outsider remains clearly present in a homogenous society. Freshman Chirayu Joshi, a Nepalese student, said, “It’s like living in a bubble. You’ve been here your whole life, but you don’t quite mesh with everyone. You do what they do, but you don’t belong.”

Nonetheless, persistent stereotypes, especially those about our dark skin tones, interfere with our lives. Every now and then, I overhear a bitter 아저씨 (middle-aged man) grumbling about how 외노자 (foreign workers) shouldn’t take Korean jobs. These comments sting, but they’re less common now.

In some ways, Korean society took a few steps backward. The obsession with beauty, for instance, only intensified. “While I’ve lived here for so long, I still don’t feel like I’m part of it,” Kojima said. The strict beauty standards of Koreans remain in stark contrast to the diverse faces seen elsewhere.

Strive for Belonging

Despite all the challenges, most Koreans treat me with genuine warmth. For instance, our landlord gave me rhyming books that once belonged to his grandchild, and a lady at the nearby mart handed me some old but clean clothes from her grown-up kid. Eighth-grader Willy Wei, a Chinese student who went to Korean elementary and middle school, said, “People were always trying to help me, even when I didn’t speak the language. They were kind then, and they’re still kind now.”

However, many of us still feel as if we exist on the fringe. We’re part of the fabric of Korea but loosely stitched at the edges. At first, this kindness feels amazing, a reminder of how welcoming Koreans are. But after a while, it hits you; this generosity, though well-intended, reminds you that you’ll always be seen as a “foreigner.” Moments of affection can make you feel at home, but you’re still an outsider looking in. In the end, maybe, that’s the best we can hope for. We’ve grown with it, but the question remains: will we ever truly belong?

Dylan • Oct 24, 2024 at 7:31 pm

Being a foreigner, I can relate to this even if I was born in Korea, I still felt like a foreigner. Now I feel like I’m not the only one who feels like this thank you for making this article ^_^