“That’s on period,” or “Nah, that’s cap,” echo through student-packed hallways at majority-white American and international schools alike. Labeled as “Gen-Z” lingo, these words jump from mouth to mouth as countless kids hop onto the linguistic trend via platforms like TikTok. Although framed as hip and new, the root of this language dates back far into Black history, one which we should be aware of before we throw around misappropriated terms. However, white teens in the US and international school students halfway around the world from America use it without any education on Black history due to media outlets that promote AAVE as “cool slang for conversational English.”

African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is a dialect (the variety of language that differs from others by phonology, grammar and vocabulary) that originated within various regions of the Black community. On many occasions, its undertones differ significantly from conventional English.

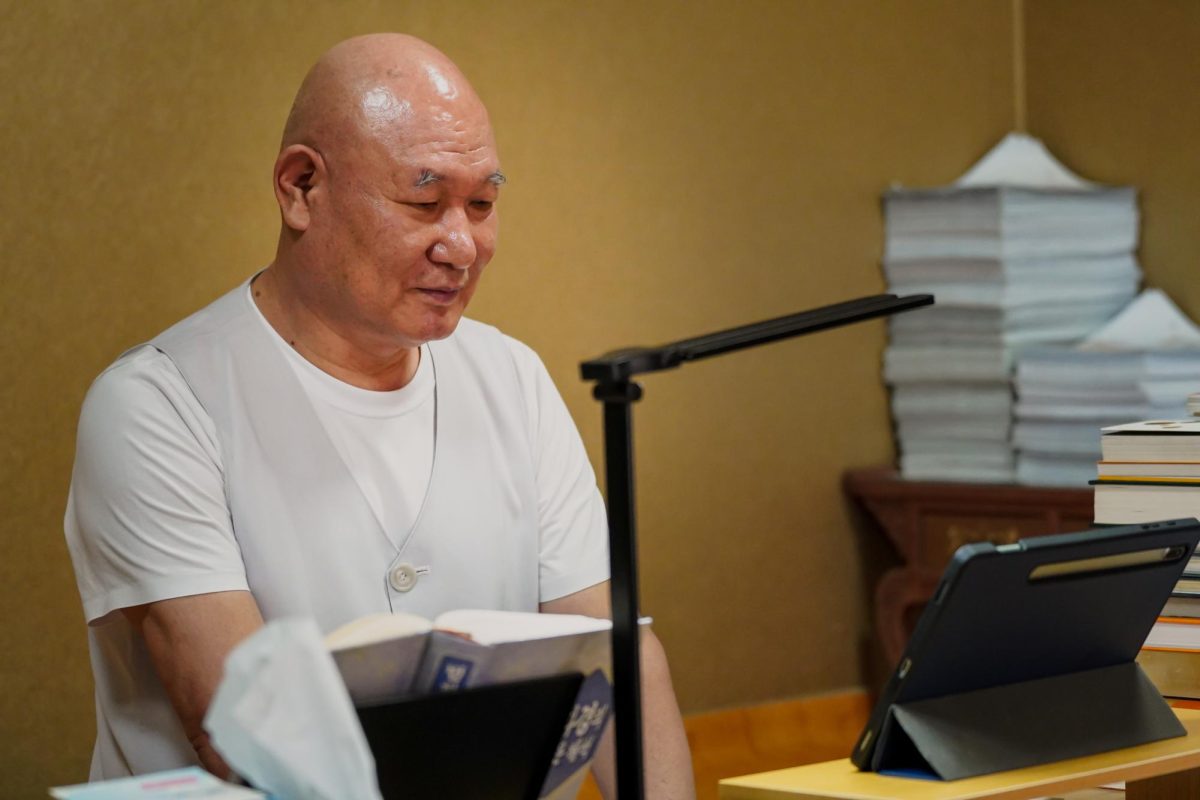

Ms. Downie, an African-American teacher at DIS, said that it would take hours to explain the full cultural context to someone unaware of the nuances. “[For example,] the word dog would seem like a negative connotation, but it is actually used for a close and trusted friend. Like that’s my dog for life — that’s my homie for life. And it’s kind of D A W G, dawg. Like we’ve been friends for 18 years. That’s my dog,” she said.

This specific language stems from oppression in the thick of the slave trade in the 17th century, as owners forbade their slaves from enjoying their own culture and speech. As an alternative communication method, AAVE started to blossom among Black Americans as a means to connect with each other.

“Some of the words are just completely made up, but the way they’re made up is usually based on shared experiences that are particular to African American people. It’s almost a kind of code because another Black person would understand exactly what I am talking about if I say this word, but everybody else would be clueless,” said Ms. Downie.

From an outsider’s point of view, one may question the significance of this culture. However, AAVE holds far more meaning than what meets the eye. “As a Black person growing up in America, our initial roots and traditions, which are so important to any culture and people, we’re stripped away, beaten away, murdered away,” Ms. Downie added.

Unfortunately, ignorance of these issues leads to misuse and stigmatization. “Most people don’t even understand the concept or where it comes from. They get into trouble when they’re using it incorrectly when they think it’s cool to go up to a person of color and use it. There’s common sense of when it’s okay and when it’s not and what things are okay and what’s not,” Ms. Downie explained.

Schools often teach Standard English and discourage the use of its so-called “fragmented” counterparts. For example, a white teacher banned words in AAVE such as “that’s cap” “period” and “big dawg” and put them down as inappropriate slang. The belittlement of this dialect often results in muted children and an ultimate disinterest in education. Due to deeply-rooted stigmatization, many Black youths hide their native dialect to be accepted by the “real” world.

The deep-rooted underappreciation for AAVE extends to the Black population as well, as they often deem their own dialect as “improper” and discourage others from using it. This alienating stereotype exacerbates the lack of representation and correct identification of Black English.

What’s worse, nowadays, the younger generation reappropriated the vernacular and coined it as Gen-Z slang. Imitation is the greatest form of flattery, but inappropriate usage erases the roots of heritage, which holds far more cultural nuance than mere internet slang.

Due to the notion that AAVE sounds “broken,” netizens often mock it to poke fun at an ignorant person. To a population with a long history of painful oppression, this stings. Ms. Downie said, “When you have your culture erased and you have to make a brand new one from scratch and then somebody comes and tries to use it in a way that is A, unflattering, or B, kind of sarcastic, or C, in a way that’s derogatory, then we have problems… You want to take out little bits and pieces of a culture that was made out of a little bit of nothing and a lot of ingenuity.”

As AAVE has already penetrated everyday speech around the world, we must focus more on the cultural nuances and context within the phrases. As Ms. Downie said, “When I put on 한복(han-bok), I make sure that I tie my bow correctly, my hair is above my collar, and I am wearing the correct kind of shoes and socks. If I’m going to do it, I’m going to do it right and study so that I’m not messing or mucking up anything.” Give credit where credit is due, and use AAVE in the right TPO (time, place, objective) and context to add a fashionable, well-educated flair to your conversations.