“In elementary school, I wanted to be a florist. Now that I’m a high schooler, I’ve opened my eyes to reality, but I’m not sure what I want to be,” said Somin Jin, a second-year student at Hyehwa Girls High School. When children in Korea first set off on their educational journey, they bask in whimsical dreams — some picture themselves as athletes, some others as influencers and celebrities.

But as soon as they graduate from elementary school, students join the race to earn the top score in school tests or a “1등급 (Rank 1)” on the Korean college entrance exam. To claw their way to the top, students scurry from one 학원 (hagwon, private education institute) to another. Amid their busy lives, many lower their expectations or lose sight of their future altogether and mindlessly trudge along the road to college on an endless treadmill of study, sleep, study, sleep. This renders them unable to think of potential college majors, which proves detrimental in Korean society, where many find it hard to change their field of study. In fact, many universities place restrictions so that students often cannot transfer across departments, which leaves a limited number of choices.

Part of this comes from the employment crisis in Korea – as many as 4 of 5 university class of 2024 graduates quake in their boots as they face their impending graduation without a job. As a result, more high schoolers search for stable workplaces with guaranteed employment after college.

The “의대 광풍 (medical school fever)” that rages through Korea exemplifies the thirst for a job for life. Yoochan Shin, an ex-University of California, Berkeley student who re-entered Gachon University College of Medicine, said, “I used to think the [the medical school craze] was stupid, but now that I’ve lived [in Korea] for 3–4 years, I understand why [students] are forced to make that choice. I don’t want to be pessimistic, but it’s true that for most people our age, the future of Korea does not look bright at all because of plummeting birth rates and budget cuts to the science and engineering industry. Might as well get a secure gig.”

This resonates with current students as well. Korean high schooler Yeongwoo Choi said, “In terms of career values, stability, the reputation doctors have in Korea, and the paycheck all influenced my decision to pursue medicine as a career. Among those, I still put stability as my highest priority because of the employment crisis.”

The “med-school craze” plagues diverse age ranges, from elementary schoolers who attend private camps to boost their acceptance rates to adults with white-collar jobs who retake the Suneung (the Korean college admission exam) to enter the prestigious field.

A preference for STEM majors prevails even among those who view medical school as out of their league. “Although I chose to study the humanities because I believed I wouldn’t be able to succeed in STEM, a lot of my family members suggested that I reconsider my major for better job opportunities,” said Jin.

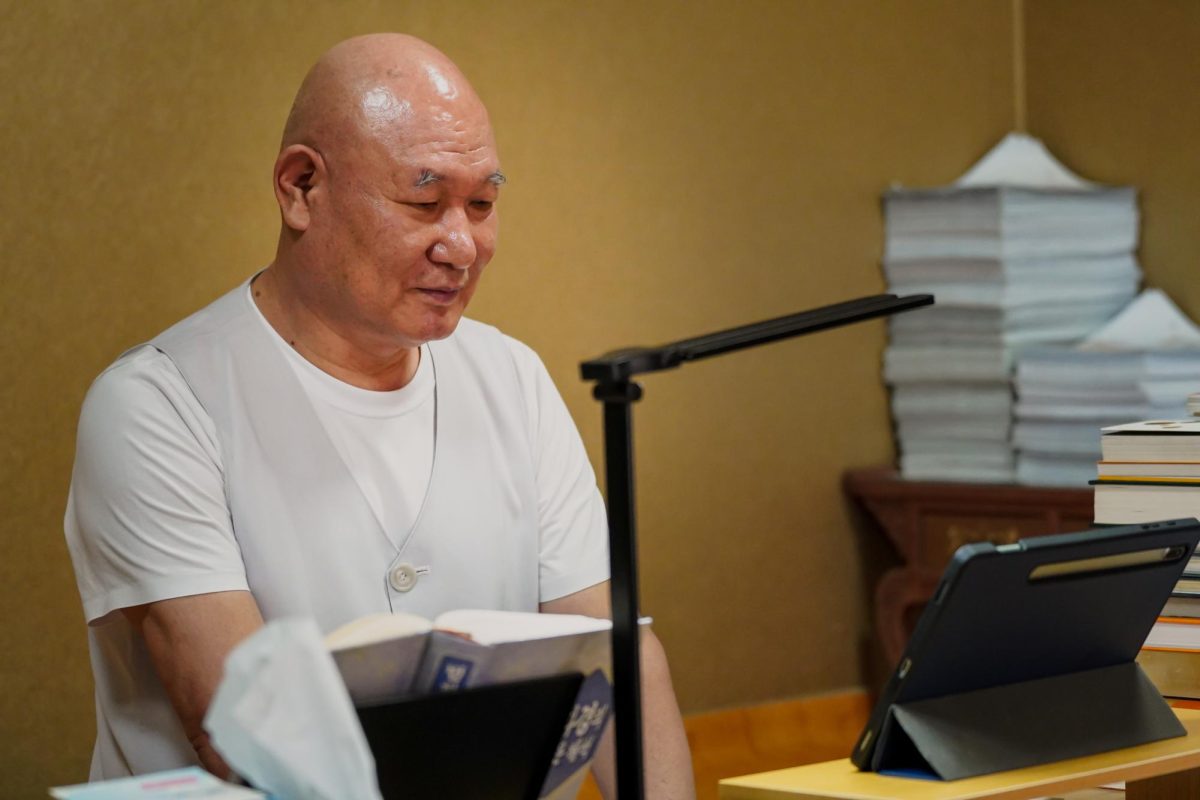

Such preferences only gloss over the tip of the iceberg. “When I talk to my students about their career choices, most of them say that they want to go to medical school or that they don’t know what they want to do,” said Seungwoo Kim, the deputy director of The M Math Academy.

Teens run on proverbial hamster wheels to survive in an extremely competitive environment. Kim said, “[In our education system], our children have less and less time to plan their futures as they get older, and they only study to go to a prestigious college and get a good job. I’m worried that we’re pushing students to the edge with all the rigorous studies.”

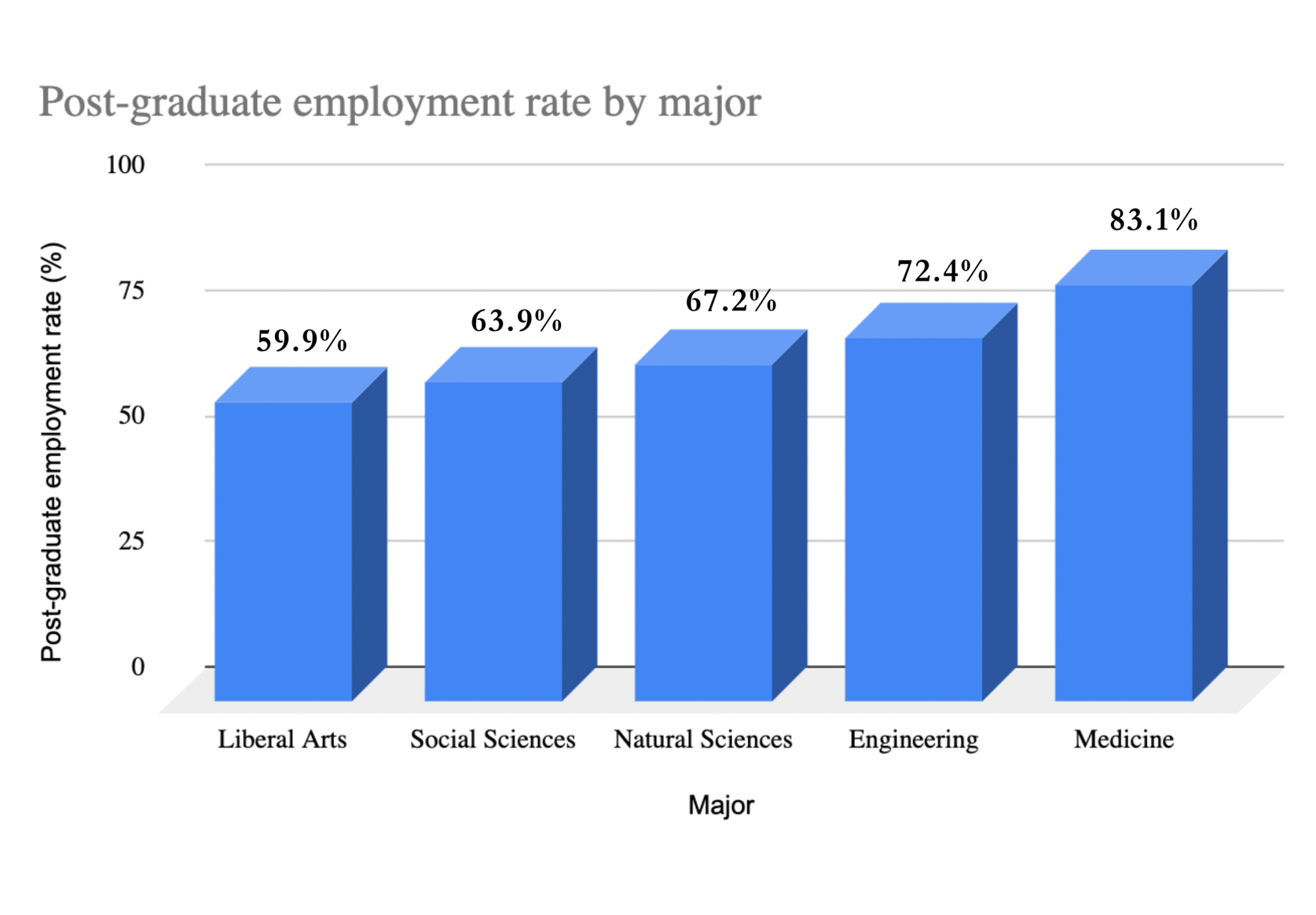

Due to worries about her grades, Jin followed this path as well, even though the disparity of employment rates of non-STEM students and their STEM counterparts rose by 12.5%p.“I chose to stick to humanities as a major even though I knew it’d be extremely hard to find a job along the road. I think high school is more about getting good grades, and non-STEM majors have it better off in this aspect.”

The lack of a specific career goal often leads to burnout and lethargy. “Since I haven’t chosen a specific career path, I struggle with what extracurriculars I should do. I also find it hard to set concrete goals and push myself,” said Jin.

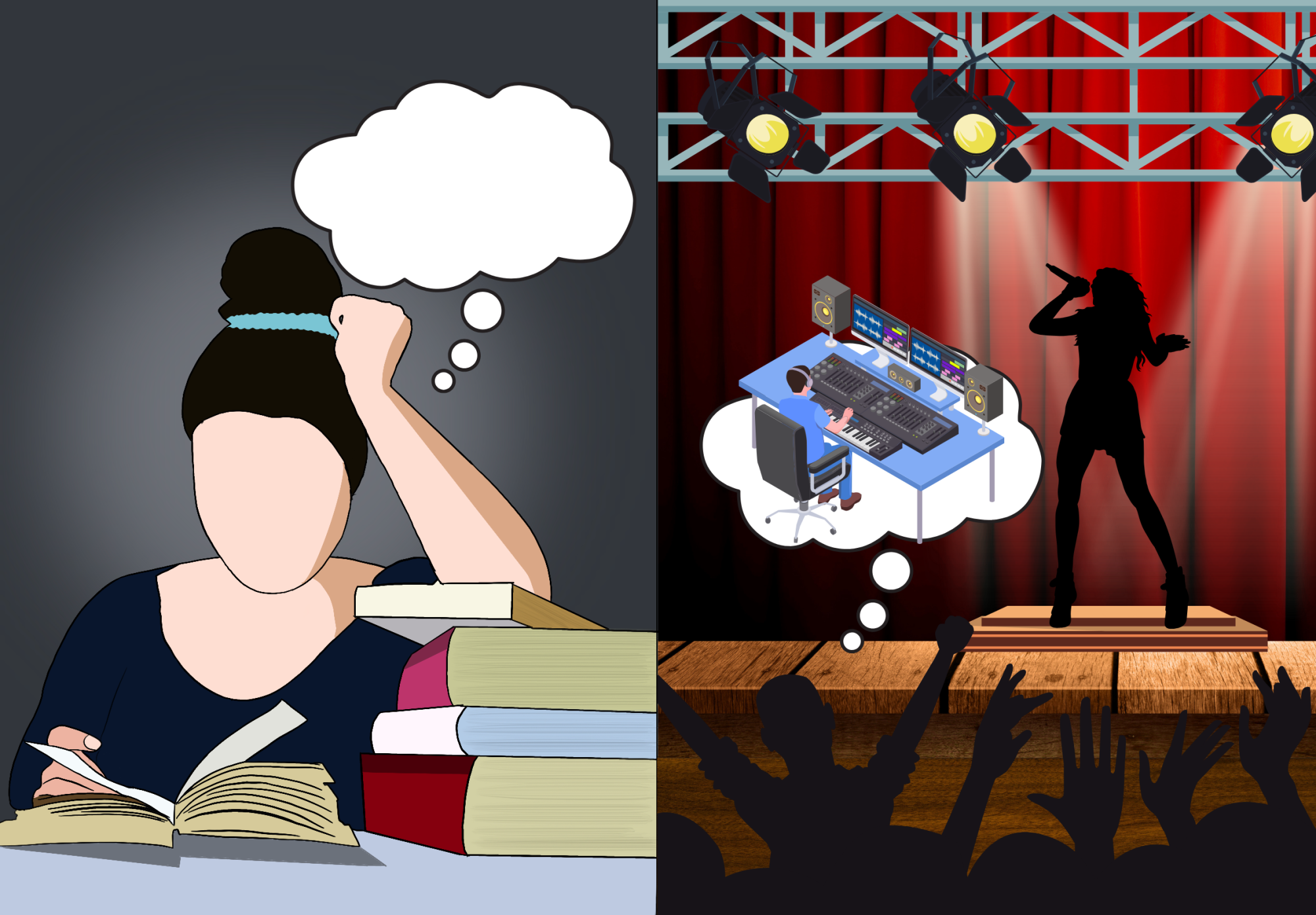

Nonetheless, some students make the most out of their experiences and reflect them in their career choices. “At a school retreat, last year, I saw a friend perform blissfully onstage. It wasn’t like I directed the performance or had any part in it, but just seeing it made me feel like my heart was going to burst. After that, I joined our school’s drama club, and at the curtain call, I felt a sense of pride I’d never felt before. That was when I decided that I wanted to be a TV show producer,” said Dayun Song, a student at Hyehwa Girls High School who aspires to major in media communications.

Despite the hardships that come with becoming a producer, Song, driven by her passion, motivates herself to step closer to her goal. “Compared to when I was in middle school and didn’t have a specific career goal, I study harder these days and also give my all in the extracurricular activities I do. A lot of Korean students dip when they move up to high school, and although I am one of those people, my grades dropped less than my peers’ did,” Song said.

Personal experiences play a crucial role in identity formation and career selection. However, many Korean students lack the opportunity for self-development due to their busy lives and push back thoughts about their future to “after midterms” or even “after the Suneung (college entrance exam).”

Korean middle and high schools offer career training programs to lend struggling students a helping hand. But teens, including Jin, find little to take away from these programs and view them as a formality of the education system. “Although there might be a limit to how much individual support schools can provide, I think it would be helpful for schools to divide into humanities and STEM and have career searching sessions. I also would like to see more practical information, such as the career paths I can look for in certain majors and licenses that I might find useful when applying for a job.”

Both Shin and Song also emphasize the importance of experience. Shin said, “It’s extremely important to experience a lot of things, especially when you are younger. Whatever you do in high school, if you put effort into it, it’ll help in the future, even if it seems irrelevant. The older you get, the fewer choices you have, so even though academics are important, experience as many things as you can when you’re younger.”

The desire for a stable career sets a high bar for grades among students. Many are swept away by the race to a lucrative major and ironically emerge from graduation with no idea of what they want to pursue. Teens in Korea long for the chance to catch their breaths and plan their futures, but for the time being, the best they can do is hope for less competition and better career education.